Rob Zacny, a freelance writer who often specializes in computer games, recently wrote a piece for the new GameSpy series ‘Command Lines’ titled ‘Quick-Loading Kills Strategy Games‘. Detailing the practice of using save games and constant re-loads to overcome obstacles found in many strategy games, Zacny states that not only is this practice ruining strategy but also encourages lazier game design. It’s a good read that asks some interesting questions about the impact player culture has on the larger question of game design and mechanic implementation. I want to push this analysis a bit further to discuss larger themes of how player culture impacts the actualization of play and how the ‘quick-load’ issue raised by Zacny points to general questions on the interactions between game players and game designers.

Take this quote from Zacny:

“When we start rigging outcomes by reloading after suffering setbacks, we are cheating ourselves. If the heart of a strategy game is interesting decisions, it is their consequences that give those decisions meaning.”

Zacny goes on to state that strategy games don’t work if players constantly re-load in order to ensure success. As a long time player of the Civilization franchise, I am certainly guilty of this crime. My desire to achieve absolute control over the situation means I can’t or won’t tolerate ‘chance’ events that could disrupt my larger play goals. While I’m trying to build a perfect narrative, I have, in effect, robbed myself of any narrative at all by eliminating the possibility of deviation. Zacny echoes this sentiment when he states that this ‘perfect narrative’ made possible by re-loading is anything but as the aim of strategy games is to provide interesting decisions- and the consequence of those decisions are what create meaning.

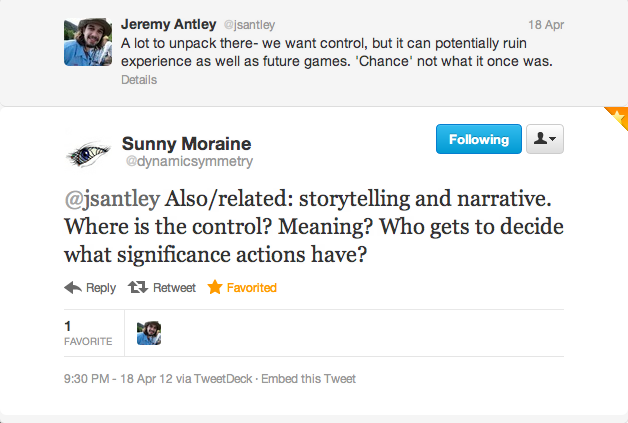

When I tweeted this thought a few weeks ago, Sunny Moraine (@dynamicsymmetry) responded with the following:

This is the larger issue at stake with Zacny’s article- who should have control over the narrative and meaning of play? Clearly, game designers create AI’s (by which I mean algorithmic intelligence) that attempt to assert total control over the narrative and meaning. Players who constantly save and re-load could be seen as attempting to reassert control over this narrative and create their own meanings- a prospect not considered in Zacny’s essay.

This last point is made clearer if we briefly leave the world of games and enter the reflective mode about games found in literature. Steven Belletto does this in his book ‘No Accident Comrade‘ through a discussion on the use of ‘chance’ narratives, linked to the emergence of Game Theory in 1950’s popular culture, as found in American writing. Analyzing Robert Coover’s novel ‘The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J Henry Waugh, Prop.’, Belletto details a scene in which the narrator, while playing through a fantasy baseball setup of his own design, enacts revenge for having his star player killed by an errant bean ball, produced by the narrators own roll of three ‘ones’, by ‘killing’ the offending pitcher later in the season through a purposeful roll of three ‘ones’. Belletto states:

This last point is made clearer if we briefly leave the world of games and enter the reflective mode about games found in literature. Steven Belletto does this in his book ‘No Accident Comrade‘ through a discussion on the use of ‘chance’ narratives, linked to the emergence of Game Theory in 1950’s popular culture, as found in American writing. Analyzing Robert Coover’s novel ‘The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J Henry Waugh, Prop.’, Belletto details a scene in which the narrator, while playing through a fantasy baseball setup of his own design, enacts revenge for having his star player killed by an errant bean ball, produced by the narrators own roll of three ‘ones’, by ‘killing’ the offending pitcher later in the season through a purposeful roll of three ‘ones’. Belletto states:

“…the results of Waugh’s intervention are paradigm-shifting because a chance roll was converted into a willful strategy. The novel is about the veils between fiction (or myth) and reality: once Waugh intervenes to adjust the dice, the characters in his universe intimate the guiding hand of the Association’s author, and deify the players involved.”

The implications of this ‘willful strategy’ become apparent later on:

“The Universal Baseball Association, baseball functions as a metaphor of both religious control and of the control of game theory: “the canonical form of M,” like the M-Game in Solar Lottery, alludes to minimax, the notion of balance and equilibrium, so that “old strategies, like winning ball games, sensible and proper within the old stochastic or recursive sets, are, under the new circumstances, insane!” (148). In a world in which Waugh has loaded the dice, former normative standards (“old stochastic or recursive sets”) become irrational-“insane”-because the rules of the game are no longer chance governed. While manipulating the dice is a way out of the “loneliness” that came when “pattern dissipated, giving way to mere accident,” this control of accident has religious reverberations, as well as secular ones.”

If we extend this idea to the play-design mechanics found in many strategy games, then we can begin to see why players would embrace constant saving and re-loading as the control these actions provide make the ‘old stochastic or recursive sets’ found in the design of strategy games cease to be normative. They become, in fact, insane from the players point of view. Again, Zacny points towards a players comprehension of this insanity when he brings up the ridiculous challenge of attempting to beat the more difficult levels of Panzer Corps or the Total War franchise of games:

“It’s not hard to see that high difficulty settings…are predicated on the expectation that players are reloading to achieve perfect victories, or else are superhuman.”

This is a difficult problem to solve as game designers must balance providing satisfying play through increasing levels of challenge, all the while making sure that the player has the ability to overcome these challenges. The save game becomes a tool players use to help overcome these challenges- a tool which designers tacitly acknowledge through their design.

Another angle to this player/design-mechanic relationship implied in Zacny’s article, but not stated explicitly, is that ‘quick-loading’ is a phenomena largely found in single-player games. With multiple players the issue of ‘quick-loading’ largely disappears. This is because the challenge the AI once provided is now substituted by the most challenging player of all- another human mind. Zacny suggests that perhaps strategy games could embrace something akin to ‘hardcore’ or ‘iron man’ modes that simply don’t allow saving in the middle of a mission. Unity of Command, Zacny mentions, accomplishes this task extremely well due mainly to its execution of challenging design through short bursts of play- a level is short enough that trying and failing a few times generally doesn’t discourage the player. There is another example, a way out of the ‘quick-loading’ problem, that I would like to quickly discuss- that being the design philosophy found in the design of the popular horror game Amnesia: The Dark Descent.

At a GDC Europe 2011 presentation titled ‘Evoking Emotions and Achieving Success by Breaking All the Rules‘, Thomas Grip, the project manager of Frictional Games, detailed the core design choices the Amnesia team made in production. Essentially, the entire thought behind the choices made centered on the idea that the game shouldn’t punish the player for making a wrong move- it should let the player role-play instead. For example, while many horror games use the fear of character death as a driving mechanism for creating tension and immersion in their game world, Amnesia specifically does not penalize the player for ‘dying’. If a player fails to accomplish a ‘chase sequence’ (in which a monster attempts to hunt down the player) or finds difficulty in evading the placement of a particular enemy (brought about by passing a certain point or picking up a particular item) two times in a row, the game will remove that obstacle from the players path and move it to a different part of the game. The challenge is still present, yet the trial-and-error approach is removed so that even if the player realizes the penalty for dying is very slight (like the quick mission approach embraced in Unity of Command) they still are immersed in the game world and find no need to utilize constant saving/loading to achieve success.

Now I realize the mechanics and design decisions found in horror games differ from the sort of strategy games Zacny describes in his article- yet the fundamental issue of player interaction with the design-mechanics holds true for both genres. Perhaps the solution to the ‘quick-loading’ issue is to focus on giving the player permission to cede the need for control through mechanics that create deeper immersion and less realization of the trial-and-error process that many strategy games take as a bedrock in their design. The ‘quick-load’ may be killing strategy games, but until designers address the more fundamental issues inherent in player interactions with meaning and narrative in game play, the ‘quick-save/load’ will remain a shortcut towards providing challenges that only partially compensate for the lack of control players feel.

Of course, the kind of narrative being invoked in strategy games is of a limited nature. It consists of the “story” of the game, much in the same way that the list of moves in a chess match is a “narrative.” Still, I liked Zacny’s article; I’ve often been turned off by what felt like excessive difficulty in strategy games, and this at least posits a plausible explanation for that experience. On the other hand, I don’t think that drastically altering the current standard for saving games is a good idea either; the classic example of bad implementation of a different save-game mechanic much be Daikatana, since FPS players were accustomed to being to save more often than the game allowed (of course there were a host of other issues with that game as well). Amnesia brings up a good point, though, in offering the possibility of an evolutionary rather than a static AI–what if strategy games could, without seeming to be petulant or annoying, slightly alter the AI players’ decisions to take into account how well (or poorly) the human player was doing?

Jonah, thanks for the comments.

I would argue that the narrative of strategy games isn’t necessarily limited, especially when you consider the ‘stories’ made up by players to either justify their actions or explain how certain events came to pass. Now it’s true that game designers, especially of historical strategy games, tend to frame their narrative within the historical bookends of the era they represent, yet players still have quite a bit of agency in determining the narrative being invoked. Honestly, I think there’s a lot of ‘ground’ here to uncover regarding the role of narrative in play and I see Zacny’s article and my post as just the beginning of a more rigorous exploration of this topic. (No doubt others have written on this topic, so if anyone has good examples either leave a comment here or let me know via Twitter- I’m @jsantley)

As far as save games are concerned, I think you’re right on. I can see how saves are abusing both game design and narrative (meaningful choices/consequences) as highlighted by Zacny’s article- that’s one of the reasons I wanted to discuss his thoughts in more depth. Saving the game shouldn’t necessarily go away- but as you point out, Amnesia does present a new take on how to structure a game to better suit the player and not just the game itself. (If you have time, the GDC presentation by Thomas Grip does such a good job explaining how they came to this conclusion)

For strategy games, especially long ‘campaign’-centered titles, I would like to see a lot more variability on the story spectrum other than ‘win, you progress to next level’ or ‘lose, repeat until you win’. If you lose a battle there should still be a story to develop. When you ultimately restrict a players choice to a central storyline, then you have probably dramatically increased the ‘quick-loading’ abuse problem highlighted by Zacny. It is an interesting, if not very tricky, problem to solve- yet I believe innovative design and further exploration on the interaction between players and developing meaning of a narrative could provide novel solutions.

I will try to check out the GDC presentation–thanks. I’m really intrigued by your idea of the player’s failure being incorporated into a strategy game’s story. It reminds of the first C&C Red Alert, where you would chose your next mission by selecting certain areas on the European map. It was a fairly artificial way to provide the illusion of choice (as if your selection actually altered the outcome of the game), but I appreciated the feeling that grand tactical decisions, like which country to attack next, were also under my control. I could see a combination of your approach with Red Alert’s global map, in which certain geographic areas would open or close depending on how well a player completed various missions.

It seems to me that a player who constantly reloads isn’t really interacting with the game as a player anymore. The setback that made the player reload occurred within the rules of the game, reloading essentially means disregarding the rules. A simple analogy would be a chess game with one player always allowed to take back as many moves as he wants. Under these circumstances, actual play can’t occur.

Playing a strategy game that way is much closer to a performance then, one in which minor meaningless variations are allowed, but no major meaningful deviations from the predetermined story are possible. It’s not truly interactive anymore. Ironically, wanting to create a certain story with the game is probably one of the strongest reasons to stop playing with the game and to start using it as a canvas. On the game side the equivalent would be punishing levels of difficulty or single solution scenarios, forcing the player to end play and begin a predetermined performance.

Now, if it is true that some (or most?) games require the player to end true play, then that seems problematic. Less so in genres like Adventure, but certainly in strategy titles.