“Nothing except a battle lost,” wrote Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, “can be half so melancholy as a battle won.” His view was as sober as any to emerge from the killing fields of Waterloo in June of 1815, but the Duke already grasped the extent to which the battle he had just fought would be narrativized, rationalized, and domesticated for subsequent popular and historical consumption. Two months later, he famously compared the impossibility of writing an accurate battle narrative to two different people telling the story of a ball: “Some individuals may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle won or lost, but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact moment at which, they occurred, which makes all the difference as to their value or importance.”

Scholars and enthusiasts of all stripes (Stendhal, Victor Hugo, and Rod Steiger all among them) have since enlisted words and images to capture and convey some sense of those elusive events, utilizing in the process every tool of the historiographical trade, from John Keegan’s “face of battle” conjectures to military archeology and battlefield forensics. Yet one of the very first and most popular and spectacular and controversial representations of Waterloo was not a book or a painting or a film or a reenactment or a panorama. It was a model.

Fifteen years after the battle, one William Siborne, then a lieutenant in the 47th Foot, received a commission to prepare a huge, three-dimensional diorama of the battle. The model, the first of two he would eventually craft, was roughly 27 x 19 feet, accommodating 70,000 miniature figures (roughly one for every two soldiers actually present on the field). It was nearly a decade in the making, and though it apparently began as a government contract it was also financed through private subscription and eventually out of Siborne’s own pocket; he took out a bank loan to finish it. Still, it was more than just a personal obsession. To quote one authority: “In the century before film and the sophisticated electronic media of today, a massive, highly detailed model of the most popular recent event in British history would attract substantial attention” (Hofschröer).

Siborne’s model was indeed spectacular, and can still be viewed at the British National Army Museum. But the model was precisely that: a model, which idealized and distorted. Wellington himself was sharply critical of the end result as he believed it overstated the contributions of his Prussian allies, thus effacing the essence of his tactical achievement: the care he had taken in choosing his ground, the parsimony with which he husbanded scarce reserves and resisted the temptation to commit them piecemeal, and above all the resoluteness of the British and Allied troops in the face of a day-long pummeling by Napoleon’s infantry, cavalry, and artillery. The Duke’s critique recalls Lessing’s musings on the limitations of the visual arts in the Laocoön: “No drawing or representation as a model can represent more than one moment of an Action, but this model tends to represent the whole action: and every Corps and Individual of all the nations is represented in the Position chosen by Himself. The Consequence is that the critical Viewer of the model must believe that the whole of each army, without any reserve of any kind, was engaged at the moment supposed to be represented. This is not true of any one moment or event or operation of this Battle . . .” (qtd. in Hamilton-Williams, 22-3). These objections resulted in a substantial revamping and editing of the model, removing most of the Prussian troops. Though his motivations were nakedly self-interested, Wellington had nonetheless grasped an essential point: Siborne sought to collapse diachronic sequences of events and their dependencies in favor of a dramatic vision that dilated a single moment of the battle into a tableaux claiming the authority of a global representation.

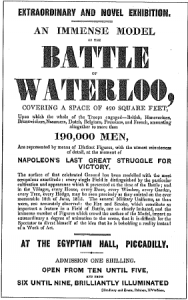

Put another way, Siborne’s model, was a fixed and static representation. The toy soldiers must have been tantalizingly tactile, and the impulse to reach out and touch them would have struck nearly every person who paid admission to the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly where it was first exhibited. But one could not reposition this regiment here, nor advance that column there and ponder the difference. The lack of direct manipulation limited the model to a purely descriptive, rather than a predictive function. In Clifford Geertz’s terms, as taken up by Willard McCarty, it was a model of, and not a model for.

Of course many since Siborne have built models for rather than models of the battle, and Waterloo has been endlessly war-gamed, using miniature figures, cardboard hex and counter board games, and finally, of course, digital games, all in the service of exposing and exploring counterfactuals while allowing armchair generals to test their mettle against the plans and dispositions of a Napoleon or a Wellington or a Blucher.

At this point I’ll make a confession: I was a teenage grognard. I suspect maybe some of you were too. So what is a grognard, you ask? A grognard is a wargamer. The name was a term of affection that Napoleon bestowed on his grizzled veterans, the ones who had been with him from the Italian campaigns to the snows of Russia to the muddy fields at Waterloo. In a sense, I’ve been to those places too. On many a day after school you would have found me hunched over a topographical map overlaid with a hexagonal grid, pushing around dozens if not hundreds of little pieces of cardboard with cryptic markings, rolling dice, and consulting charts and a rulebook, thick and closely typed. The materials were crude indeed, but in retrospect I realize these were some of my first virtual realities. You would have seen me huddled over a mess of maps and markers, but I would have been busy turning Lee’s flank at Gettysburg or plotting the movements of an armor division racing across the Sahara desert, or even (this was the eighties) working to counter a sudden Soviet lunge into the cities of Western Europe.

One great virtue of tabletop games is that, by their nature, their rules systems are absolutely transparent. Everything the players need to play the game must be in the box, and the formal model underpinning the game system is thereby materially exposed for inspection and analysis. Many gamers collect and compare dozens of different games on the same subject to see how different designers have chosen to model and interpret events. The hobby is filled with vigorous discussions about designers’ intents, as well as house rules and variants, because part of what comes packaged with the game is the game system. (Indeed, the term “game designer” originated at SPI, one of the hobby’s premier wargame publishers.) The following remarks from Frank Davis’s designer’s notes to SPI’s Wellington’s Victory (1976), probably still the finest hex and counter game on Waterloo, are revealing in this regard:

I will begin by saying that I cannot claim that Wellington’s Victory is an accurate simulation of the Battle of Waterloo. Like Wellington, I believe that an accurate account (much less a game) never has or will be produced on the subject of Waterloo. No soldier, historian, or game designer knows or fully understands exactly what occured that Sunday afternoon more than a century and a half ago. All I can therefore claim is that the game accurately reflects my own carefully constructed interpretation of the events of June 18, 1815. I am grateful that our exhaustive playtesting indicates that when the game is played effectively, it does in fact resemble a reasonably accurate working model of the actual battle.

Davis goes on to add: “[P]lay balance was never a high priority in terms of the overall design of the game. From the outset I was primarily concerned with the game as a teaching device which would enable players (including myself) to gain a better understanding of Napoleonic battle tactics.” Play balance, i.e. giving both sides an equal chance at winning—what one expects from Settlers of Catan or Chess or even a proto-wargame like Stratego or Risk—has been subsumed by historical accuracy, an unabashed pedagogical aim, and above all the workings of a well-tuned formal system.

My future contributions here on Play the Past will focus primarily on the genre of tabletop wargaming, or conflict simulation as it is sometimes known. While some of what I write will no doubt carry the mark of a hobbyist’s enthusiasm, I hope these short essays, along within those from others on this site, can help to restore wargames to a more prominent place in the toolbox of both game designers and educators. For both audiences, wargames have advantages that more abstract Euro style games lack. Each of these will be the focus of a later entry, but I will close by listing them briefly. The first is asymmetry. A good general did not want a fair fight. He (or she) sought to strike where the enemy was weak. How then to make an inherently asymmetrical game competitive and fun? This is a fascinating topic for prospective designers. The second advantage is ground truth. A good wargame should be able to storyboard historiographical representations of the events it depicts, meaning that given a set of inputs within accepted historical parameters, the game should deliver outcomes that are likewise within historical parameters.

Finally, given the volume of games that have been published and the relative ease with which new ones can be researched and designed (something which Phil Sabin at King’s College, London has demonstrated conclusively), it is easy to produce multiple games on a given topic allowing the exploration of a variety of different vantage points. The abstraction of combat, movement, supply, morale, and other basic military considerations into a numerically expressed spectrum of outcomes randomized by die rolls within the parameters of a situation (what systems analysts would recognize as the Monte Carlo method), makes the genre a rich source for anyone interested in the ludic and procedural representation of a dynamic, often ambiguous, literally conflicted past.

References

Davis, Frank. Wellington’s Victory. New York: Simulations Publications Inc., 1976. Board game.

Hamilton-Willaims, David. Waterloo: New Perspectives: The Great Battle Reappraised. New York: Wiley, 1993.

Hofschröer, Peter. “Siborne’s Waterloo Models.” Osprey Publishing. March 18, 2008. Web. November 28, 2010.

Wellesley, Arthur. Wikiquote. Web. November 28, 2010.

Perhaps this is beyond the scope of this site and what you plan to write about, but are you also thinking about “Conflicting the Future”? Meaning, do “future” based war games also have a place in your analysis? I don’t mean simply games with space ships a la Twilight Imperium, but games designed to simulate anticipated conflicts that have yet to, or may never, take place. I’m thinking here, as you can guess, of the many cold war games that posited both conventional “battle for Europe” scenarios as well as nuclear conflicts. It seems to me that if we want to get at models for instead of models of then imagined/anticipated conflicts can be as significant as conflicts of the past.

Sure, the Cold War hypothetical stuff is still interesting to me as an artifact of gaming history (just like movies, novels, etc. from that same time). Might or might not do something with it, but I will definitely write about the emerging crop of games on global terrorism. (Playing the present?) I’ve got GMT’s Labyrinth on the table right now and will post about it here soon.