Teaching Games as Text: The Problem (Part 3 of 4)

This is the third in a four-part series that reflects on a Composition II course taught in Spring 2013 called 20th Century PC Games. You can read part 1 here and part 2 here.

Here’s the thing about teaching games as text: it’s not a silver bullet. Introducing games into the traditional humanities curricula doesn’t magically make students more interested, nor is it a short-cut to critical thinking or application. And requiring students to play and analyze games causes a lot of problems that teachers generally don’t experience with print-bound (novels, essays, poetry) or even linear audio-visual material (such as film or TV). Studying a game requires the same pedagogical bag-o-tricks that studying any other cultural text requires, plus a few more tricks up one’s sleeves, because games often don’t work in the same orderly ways that linear texts do.

Contrary to expectation, one of the greatest challenges I have found in teaching video games in the classroom is student resistance. It may be that at the lower levels, with uniformly younger students, games can make school more fun, but at the higher levels, where students are uniformly adults (if often very young adults), students generally don’t welcome the idea of being required to play games for homework. Although I took cost into consideration, and made sure that they were spending no more on games than they would have on the textbook that I was replacing with the videogames in the Composition II curriculum that was my framework, I found in student evaluations that many students considered purchasing videogames an undue burden.

Although my students framed this as a purely economic consideration in their evaluations, I believe that there is something deeper going on here: a clash of discourses, if you will, in which students are resisting any bleeding between categories of texts. This was exhibited in other behaviors as well, both in how students approached assignments and in how they approached (or retreated from) the course itself.

In each of four sections I have taught that used videogames as the primary texts for analysis, I have had an alarming rate of what I call “roster shuffle” in the first two weeks, as I mentioned in the previous post in this series. Some students who dropped the course expressed discomfort with the theme of the course before dropping. Most of the students who dropped were female, suggesting that perhaps the way that we gender videogames in popular discourse (often as an exclusively male pursuit, despite obvious evidence to the contrary) causes these students to perceive themselves as outsiders even in the classroom. Of course, this is a problem that cannot be solved merely in the classroom, although I had hoped that my being a female instructor would help to mitigate this challenge. It did not.

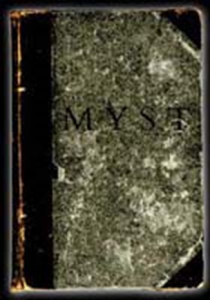

–the manual to Myst

Moreover, introducing games as text with all the same techniques we assign traditional media texts causes students to approach the games with the same apathy that they approach their usual reading assignments. That is to say, they simply don’t play the games because they simply don’t do their homework. Part of my experience in this regard, of course, is that I was teaching a special section of a course that is required of nearly every student at my institution; general education courses have a poor reputation in student discourses, and somehow become labeled less important to students, and simply adding videogames into the mix does nothing to solve this problem.

Indeed, adding videogames may exacerbate the problem. I discovered something unexpected, but not inexplicable. Academic discourses tend to colonize whatever they touch. We in the academy tend to find a new subject and merely apply our familiar practices to the subject, assuming that our practices are good and noble. Accordingly, the academy wields great social power. It is a normalizing force, and often provides the means by which individuals are judged and sorted. In a typical classroom, power is centralized at the instructor, and the students are expected to conform to the instructor’s expectations and values.

If this sounds like a postcolonial reading of the classroom, that’s because it is. Postcolonialism may in fact provide the best explanation for some of the most frustrating student behavior I have witnessed in these classes, because if we see students as the marginalized group and the established academics as the center then student resistance to classroom activity and homework becomes a colonial struggle at the margins, a conflict between the popular world and the ivory tower. In this framework, when students object to incorporating videogames in otherwise traditional curricula, they are not claiming that videogames are beneath study, but rather that videogames are outside the center’s power and must be defended from further colonization. That is, they are resisting cultural appropriation.

Although students often find older literature pointless because they don’t see it as immediately relevant to their lives, they also find incorporating popular culture in the classroom as being a little too close to home, or they see the methods and conclusions used with popular culture as being somehow inauthentic to the nature of popular culture. I was told repeatedly by students that the games were “just games,” just as I have been told by students in literature-based curricula that analyzing a story “killed” it.

The problem isn’t inherent to games, but is a problem of context. The classroom is inherently prescriptive—we tell our students what to do and how to think and we expect them to obey, and we say it is for their own good. What’s more is that the academy has only recently started to value popular culture on its own terms; without a full understanding of the contexts and uses for which popular media is generated, how can we teach these texts without completely colonizing them and appropriating what is rightly our students’ cultures?

We must consider carefully why we are bringing games into the classroom. Because they are complex texts worthy of study? Certainly. But how will we decide what games to teach? We could try to teach the most popular games; this runs the risk of always being a little behind the curve and also of colonizing those popular cultures even further. We could try to assign the most “literary” games, which will tend to be indie games in the same way that “literary fiction” will tend to be from smaller presses and more niche audiences. But then we run the risk of presenting only the kinds of games that fit the traditional literary canon’s already too-gloomy purview, and of again subtly but powerfully telling our students that only certain high-brow tastes are worthy of study in the academy, that truly popular pop culture isn’t intelligent enough. I have no desire to give students that message; I came into the academy to change that theme in the canon, not to spread it to new media, and I suspect I am not alone in this.

I made it my project in the first course to provide a historical perspective on the games; that is, to assign games according to a period and to arrange the curriculum in a way that stressed each game’s place relative to other games and to general technological and historical movements in time. This approach harmonizes with the way we usually teach traditional media, as we tend to divide literature and film into periods and design courses around those divisions. I think this is the best approach, as it is less threatening to both students and the established academy, but also does a great amount of cultural work. By teaching students the major movements and developments in game history, we can help them make sense of the present state of whatever cultures they are coming from, as well as to apply established and accepted academic practices.

Games are not ahistorical, perpetually new media. In fact, I’m not even sure we can call them “new media” anymore. At this point, we can draw several periods in game development, and there are now so many divergent genres (however we define that term) that it’s impossible to see videogames as a unified concept except, perhaps, in the same way we might talk about “books” as a unified concept. Of course, the label “new media” isn’t going to disappear soon; we still call the novel “novel,” after all, a label of newness it’s borne for a few centuries now.

But when we assign games for their historicity, we run into two problems: technical compatibility, and alienation to modern audiences. There are several games that are indeed quite significant historically that are impossible to assign on a large scale, because they are not compatible with the newer technologies that our students have access to. In some cases there are “graphical update” editions (often fan-made) available, but then we run the risk of confusing our students about the actual nature of the historical objects, not unlike assigning a paraphrase to get around language confusion in Shakespeare. Hardly an ideal solution if the goal is to situate the text historically.

The technological problem is solved in some ways by popular download services, such as Steam and GOG.com. For my own part, I limited myself to games available via such services, because I expected this would mitigate technological issues for my students. It does, but only to some degree. For one, this limits what we can canonize only to what has been distributed by these means, but that

is not a new problem. Until recently, instructors have been generally restricted by what texts and editions are currently in print (online archives are alleviating this restriction somewhat for print media, though). Still, students are not as technologically literate as we think they are. True, they are digital natives, but a native speaker of a language cannot explain how they use the language without some training, and likewise many of my students struggled with the basic concept of purchasing, downloading, and installing a game from these services. To make matters worse, many of the games are incompatible with Apple products, which many students had. In some ways, I found myself having to teach at a level akin to teaching students how to hold and open a book to the correct page.

The other major problem with using a historical perspective on games is that gameplay conventions have changed so much that we cannot assume that a student will be able to understand how to operate a game that is, in fact, older than she is. My course was a freshman-level course, and mostly had freshman-level students. I focused on games from the 1980s and 1990s in my course; most of my students were born around 1993, the same year that Myst was released. The notion that they had to type commands into the older games was utterly foreign to them; they struggled with it in much the same way that students struggle to read Middle English when we assign them Chaucer. Some of the games were designed to use number pads; many students were playing on laptops that lack number pads, so the controls made no sense to them. Perhaps the gaming convention that seemed strangest to them, though, was the notion that the manual is an integral part of gameplay in older games.

This is not my students’ fault in any regard. By asking them to download the games online, my students were stripped of the material experience that made the manual an obvious resource when we bought our games on floppy disks in elaborate packaging. In downloaded editions of the games, the manual is often attached in a way that seems unimportant—in Steam, it is a small link among other purely optional links, while in GOG it’s tucked into a bonus content folder that downloads along with the game almost invisibly. But, on reflection, such a stripping of original material context is not new at all to the study of historical literature. The peculiar case of Victorian novels comes to mind. Most modern editions of Charles Dickens’s novels fail to mark the divisions between monthly issues, divisions that would have been real restrictions on his original audience’s reading experience. Without those divisions, the novels seem redundant and peculiar; when those divisions are marked, though, Dickens’s narrative techniques—often ending an issue with a “cliffhanger”, and then starting the next issue with some amount of summary, just as we do now with television dramas—become glaringly obvious. Without the obviousness of the physical manual, conventions centered on the manual in older games baffle our students; we must teach them about media practices from a time they can’t remember in the same way that we do when we teach literature from centuries past.

But the problem remains of how one assigns a game in the first place. I settled on requiring three hours of gameplay for each game, but this was woefully inadequate. Three hours in Planescape: Torment, for instance, affords even an experienced gamer very little of the story. If we assign print media, we can assign page or chapter numbers. There is no such standard measurement for gameplay. And how shall we account for divergent paths in the game? I tried giving my students tasks to try to accomplish in the games; I did not anticipate, for instance, that when I instructed the class to talk to as many people as possible in Fallout, one student would choose to build a character whose stats actually prevented him from talking with anyone. We need to embrace divergent paths and diverse play experiences, but how?

Ultimately, the challenges in the course made one thing clear: the answer to the question “How do we teach games as literature?” is simply “How do we teach literature?” But that question is bigger than any individual teacher or scholar can answer. But if we are going to start with resolving problems of accessibility and canonicity, we will need more than literature teachers; we will need archivists and librarians. That might be the best place to start, then.

The comment from one of the gamer students in the previous part of this series seems awfully familiar (understatement). Looking back a year ago when I attended the course, I can’t say I agree with the sentiment expressed in that comment anymore [1], partly for reasons expressed in this article.

Near the end of the semester I found myself looking at the gaming assignments (even as a one of the gamer students) as a chore when piled upon everything else I needed to do. It wasn’t even a matter of disinterest in the titles presented; Sierra’s games are amongst my favorites, yet it was around when we reached Sierra’s games that this “chore” feeling began. But to be fair, I do feel this had much more to do with poor time management on my part as well as the issue which follows: I often found myself either enjoying some games much more than others or enjoying one game enough that upon moving to the next game, I would find my interests still lying with the previous game. An issue would arise, however, that I would continue to engage in said previous game even as the class moved on to the next games, such to the point that upon reaching Ultima IV, I found myself too entranced with Commander Keen, yet upon starting to play Ultima IV, I was “too busy” playing it to play King’s Quest or Space Quest (and I’m really kicking myself for forgoing those). I do not seem to have this issue with more traditional media in which I do not directly interact with their contents; with books, papers, movies, and television shows I am more capable of “moving on,” I suppose.

With regards to “what games to study and why to study them,” whenever I look at academic studies on games I often wonder not quite so much “why do I see the games I always see discussed,” but “why don’t I see game X, which I know would warrant intelligent, meaningful discussion?” In high school I was usually presented with the classic set of books to read: Catcher in the Rye, Of Mice and Men, The Great Gatsby, Great Expectations, Lord of the Flies, an obligatory Mark Twain book or two (out of apparently the only two that are of any importance), ditto for Shakespeare plays, and at least one Edgar Allen Poe story per year that I desperately wanted to understand as it sailed gracefully over my ever-hurting head (Poe is cool). Also included would be one generally “fun” story which we would gloss over before returning to “the hard stuff.” I mention this because the last time I searched for game studies, I felt as if I was seeing only a set of “classic” games for study much like I was given only a set of “classic” novels for study in high school. As I recall asking in class, “Why not Wing Commander?”[2], a game franchise which pushed many boundaries in player immersion, narrative, and graphical presentation, both in-and-out of the game. Is what I’m seeing that, regarding games, the media may now be fairly mature but the study of it much less so?

Oh yeah, and that Fallout character died a lot when I played him like that since I chose to attack everyone out of roleplaying the character as becoming increasingly frustrated as he failed repeatedly to communicate; he at least tried to do so though, resulting in a beautiful, if gruesome narrative with many branches. I did feel that such a divergent play would have at least some importance, though I apologize if you felt as if I tried to deliberately undermine the assignment.

[1]: “I feel the subject matter of the course allows one to be more engaged in writing and is effective in teaching students how to write good papers, the main point of the course.”

[2]: I recall you originally said that one reason for not choosing it was its relative unavailability, but now the entire series can be grabbed on GOG.com. Should you ever assign the first game, make a point of having students check out the manual.

Again, thank you for adding a student voice to the conversation.

The question “Why not ____?” is a very compelling one in both literature and popular media studies. It’s actually one of the reasons I went into English. And, indeed, when the canon settles down, Wing Commander may find a place in it, because I know a lot of designers hold it dear (if not always the scholars).

And I don’t think emergent behavior is deliberate undermining of assignments. Teachers should learn to roll with these things; it’s a hard teaching skill to learn and practice, though, and in a way we need to behave like game designers receiving test data when we find that assignments don’t quite go as planned. Note it, look for the patterns that allowed that moment to emerge, and then evaluate if it’s a feature or a bug and respond accordingly.

As I have argued, anything assigned has the potential to feel like a chore. Even in my own self-directed research, sometimes the gameplay or the reading or even sometimes the writing (which is usually my favorite part) feels like a chore–something I know has to be done to get the result I want. I’m not sure what we should do about this in the classroom, though. Do we accept that assignments will not be fun? Or do we try to find ways to make the classroom more student-directed? Would flipping the classroom prevent the chore feeling, or would it only exacerbate it? We would need a lot more teachers and students sharing their experiences to know for sure, and then a meta-study to compile that.