Luke Pullen is a long-time player of strategy and role-playing games with a BA in Classics and German from the University of Tasmania. He is interested in the ways games portray past and present cultures as functioning systems. Luke sternly disapproves of “this Twitter business”, but can be contacted via his (irregular) blog (lukepullen.wordpress.com) if one is determined.

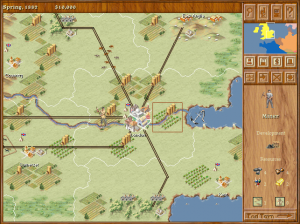

Frog City Software’s Imperialism is, as the name suggests, a game of grand politics and colonial empire building. Released in 1997, the simple design and workmanlike aesthetic of Imperialism, described by its publisher as “a thinking man’s Civilization” (the past truly is a foreign country), have long since been overshadowed by other, more glamorous strategy titles. This is a shame, because Imperialism‘s musty Victorian exterior hides the mind of an evil genius and some very sharp commentary.

In Imperialism, the each player takes command of a European ‘Great Power’ in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. The goal: to become the greatest of the Great by growing your nation’s economy, building an enormous military and bringing ‘civilisation’ to the less powerful nations of the world, whether they like it or not. Like many strategy games, Imperialism provides warfare, trade and diplomacy as tools to achieve this end.

At heart, though, Imperialism is a game about the development of infrastructure and management of resources, and incidentally about committing horrific crimes against less technologically advanced peoples, much like the Sid Meier/Brian Reynolds creation Colonization. Like Colonization and most other strategy games, Imperialism begins with nations developing their economies and seizing terrain containing useful resources. Also like Colonization, the game offers the player an easy route to development via foreign trade, but tends to punish a lack of self-sufficiency in times of trouble, when a couple of blockaded ports or an uncooperative trade partner can bring your economy to a grinding halt.

The uniqueness of Frog City’s Bismarckian moustache-twirler is only revealed in the game’s devilishly clever later stages. In Imperialism, improving infrastructure, recruiting armies, and researching technology all cost money, and there is only one way to make enough cash to pay for all of your satanic mills, painting-the-map-red and Orientalist follies: exports. There is a catch, though: unlike many strategy games, in which markets are abstract and tend to soak up whatever you throw at them, Imperialism forces its players to find other nations that are able and willing to buy particular goods. It’s not enough to have a pile of trinkets to sell: you have to actually find a buyer.

It gets worse. Technological improvement increases industrial productivity, but each round of new technologies is more expensive than the last. At some point, the industrialised nations’ ability to make things will exceed the market’s ability to absorb them, and you will find that you are competing not just for resources, but for markets. Fail to shift enough units, and you won’t be able to afford better technology; fall behind in military technology, and you risk becoming the beneficiary of someone else’s civilisation. This is a game in which failure to fob off enough chairs and petticoats can result in your grand empire being consigned to the dustbin of history.

In fact, economic growth in Imperialism requires an awful lot of gunboats and cannons, both to protect your trade network from your grasping ‘peers’ and to create new captive markets bastions of civilisation on which to foist your knick-knacks. Since keeping your little imperialists in gins and tonic and bleeding-edge pith helmets costs ever-increasing amounts of cash and raw materials, to the point where it begins to resemble some sort of stealth-helmet fiasco, the pressure for both economic and military expansion never lets up.

Imperialism has various mechanics to facilitate this competition for markets: bribes, boycotts, subsidies, trade concessions and outright conquest; but the result is simple. If the economic ‘narrative’ of Colonization is about access to resources and the tension between the efficiency of finding an economic niche (what the economists call “comparative advantage”) and the need for self-sufficiency in times of war and upheaval, Imperialism begins on a similar note but rapidly escalates into a violent crescendo in which the less technologically advanced nations of the world become the economic pawns of European powers, who themselves rise or fall based on their ability to secure their international trade. The game forces its player to think about economics and geopolitics in a different way, one in which controlling demand is as important as controlling supply.

If this talk of markets seems a bit quotidian and underwhelming, consider the way some other strategy games represent trade. While Colonization, Civilization and Galactic Civilizations all have economic models built around the importance of land grabs (albeit usually of terra nullius, sometimes interspersed with passive natives or generic barbarians), each then depicts economic activity as oddly peaceful.

Colonisation, for instance, uses an off-map ‘Old World’ market with textbook elasticity of prices based on an abstract concept of supply and demand, while Civilisation and Galactic Civilisations represent trade deals as a series of bloodless bonuses. Deals are sometimes uneven, but always mutually beneficial. These mechanics have nothing to say about the disruption and dubious benefits of actually existing trade agreements such as NAFTA, not to mention the ongoing crisis in the Eurozone. The Opium War is far beyond the horizon.

In fact, Civilization and Galactic Civilizations, to name two, explicitly use technology and policy decisions to distinguish between the peaceful pursuit of economic growth and military empire-building. Such mechanics seem to suggest that the main obstacle standing between less developed countries and prosperity is their own unwillingness to just bend their swords into ploughshares and sign a free trade pact. Imperialism, by contrast, crushes the distinction between ‘war’ and ‘trade’ beneath its jackbooted feet (and in the game). Instead, you bribe or coerce a nation’s leaders into granting access to its labour, resources and markets, then funnel the profits back to your capital.

Regardless of the strategy you adopt, Imperialism is a game about subjugating other peoples. In fact, it doesn’t even represent other populations: as an imperialist, the only human beings you see are soldiers, industrial specialists and the workers who reside in your capital. In a deeply appropriate metaphor, the imperial capital, the spider at the centre of the web, is the only location where Imperialism depicts ordinary human beings. Other people exist only implicitly, in various towns and cities dotting the map. Once absorbed, the natives are never restless, and do not speak. The empire’s serfs, slaves, colonists and coolies are implied by the extraction of resources, but never shown. To the player, the world of Imperialism is only land to be exploited and markets to be controlled.

In one sense, then, Imperialism is an especially cynical example of the genre’s problematic moral outlook. The thing is, I find that Imperialism’s brand of disarming sociopathy has a critical purpose: the extent of the game’s ruthlessness, and its fixation on economic minutiae, provide an unflattering lens (monocle?) through which to view other strategy games and the political and economic discourses they inhabit.

When playing Civilization, I might choose the ‘evil’ route of conquest, but I know that in reality I would choose the ‘good’ one of trade and diplomacy. Imperialism allows no such consolations. The game may encourage its player to inhabit the mind of a colonial overlord, but it does so with an aristocratic cynicism before which the peaceful nation-building of other strategy games can’t help but look a bit myopic and bourgeois. Whereas the genocide and exploitation of native peoples in Colonisation is treated as an unfortunate side effect of American freedom, Imperialism sees all such projects as mere adjuncts to the movement of goods and capital. Imperialism constantly reminds the player that war and the global economy are part of the same Great Game.

Thaks for this; Imperialism was the only computer game I have ever played to the end (or at least until an advanced point in the game, where my computer (old Mac) simply choked on the size of the armies I was using to fight for cities).

I have not been able to find out who designed the game, but it reminds me of Chris Crawford’s early game Guns vs. Butter. I think what drew a lot of players in was not just the subjugation and exploration part, but also the urge to create the optimum arrangement of resources and developments, so you had the most productive economy you could (and the Crawford game had this in spades, but it did not have the refinement of taking an exploited colony’s lumber and selling it bck to them as chairs for a tidy profit).

Glad you liked it. I’ve never heard of Guns vs. Butter before; I’ll have to look it up.

Selling other nations’ timber back to them as chairs is one of those classic Mr. Burns moments in strategy games; you’re both extremely pleased with yourself and dimly aware that you should be appalled. Imperialism really plays to that feeling, which is one of the reasons I find it so interesting.