This is the second in a four-part series that reflects on a Composition II course taught in Spring 2013 called 20th Century PC Games. You can read part 1 of this series here.

Here’s the thing about teaching games as text: it works. But, interestingly, it seems to work better for students who aren’t already invested in videogames.

Last month, I started to discuss my experiences with teaching video games as historically situated texts. This time, I want to focus just on the advantages of this approach in the higher education classroom. Teaching games as texts offers all the advantages of teaching other kinds of texts—plays, novels, cinema, comic books—with a few added bonuses because of the interactive nature of games.

Generally, students responded well to the structure of the course (that is, those who remained enrolled long enough to provide feedback). We often assume that all young people will be engaged by games, because games are popular media, but this is not the case—and such an assumption undermines the individuality and diversity of student populations, and also ignores the historicity of videogames. Of course, in a course that is taught just about video games, and is not required for any degree program, you will get almost entirely students who self-identify as gamers of some kind, because it is a self-selected sample. But my experiment was in teaching a special section of a course that was required of nearly every degree program; this resulted in a more diverse and representative set of students, and indeed students who self-identified as gamers were the minority.

But the most unexpected part of the course’s successes is that it worked better for students who did not self-identify as gamers.

Students who did not identify as gamers tended to be more engaged, more diligent, and more critical in their approaches to the task of studying and analyzing games as historically situated objects, because they did not assume that they knew the answers already and because the very notion of games as an object of study was new to them. As a result of their distance from the subject, these students were more apt to apply theoretical concepts to the games they played, and to demonstrate this “critical play” in their writing and discussion; in short, they learned more from the course, and achieved the course’s goals more completely.

But I would like to give my students a voice at this point. Perhaps the best way I was able to measure student response was by reading their required weekly blog posts; these usually asked students to reflect on an aspect of the game of the week, but the final prompt asked students to evaluate the course critically and provide feedback on how it might be improved. One member of the non-gamer group of students wrote:

“This COMP class was pretty cool. At first, students like me, that don’t know much about videogames, would think that videogames are a little irrelevant, but they are actually part of our culture. Understanding the issues about video games and how it affects new generations, help us see how all the things are related, something that we learn when we talk about semiotic domains. For example, talking about technology advance, how videogames developed with the available technology, this same example can be seen in other fields like telecommunications, science. Also, I think that analyzing videogames help us develop a critical thinking that can help us critique other works.”

The non-gamer group was a very diverse group of students, about half female and half male, with a variety of racial, ethnic, and educational backgrounds. Yet, they worked together well throughout the semester (perhaps bonded by their initial feelings of marginalization by the topic), and by halfway through the semester had a strong voice in the class, and were unafraid to exercise it. Interestingly, although this group expressed resistance to violent games and overly masculine games, they expressed a strong preference for Interplay’s Descent and other assigned games, and were quickly able to earn the respect of the gamers by their insightful criticism of the games included in the course.

In fact, at one point the gamer group—which was exclusively male, skewed toward upperclassmen, and far less diverse—without prompting from me recognized that they had been dominating a discussion, and yielded, saying, “But we want to hear what the non-gamers say!” I suspect that this invitation to hear what other people had to say about the games was a result of the sort of reading material and approach to the games that we were using. Bringing games into the classroom allows, in some ways, for a fairer discussion of games. Employing a mixture of literary, rhetorical, historical, and game-specific critical approaches gave students who were less familiar with gaming practices tools with which to enter the debate, and showed students who were more familiar with gaming practices that their tools were not the only ones available.

Consider, for instance, what one of the self-identified gamers wrote in response to the same prompt:

“I feel the subject matter of the course allows one to be more engaged in writing and is effective in teaching students how to write good papers, the main point of the course. At least I found it far more effective than writing about such subjects as political or moral issues, those I found myself writing about in my high school AP English classes. In fact, I outright hated those subjects and believe there should be more special topics-type courses available. I would really like to see this course again with this special topic.”

This student seems to have focused primarily on his enjoyment of the course because of the subject matter. Certainly, enjoyment is a good way to create engagement, and no doubt this student learned a great deal; however, there is little in the his response about what he learned. The focus is on student choice, the ability to choose what one studies in core courses according to one’s preferences. Such enjoyment and familiarity is what we usually consider to be the advantage of teaching video games, but I argue here that the real advantage of widespread teaching of games as texts would actually do the opposite, requiring students to engage with a subject to which they have given little or no thought previously, or even have derided previously. As in teaching traditional literature, there will always be a few students who have already discovered an affinity for the materials being taught before they enroll in the course, and they will have the initial edge on other students in the same course; however, they will lose their edge as their peers quickly catch up and even surpass them, if the course is taught well.

Of course, the greatest pedagogical advantage, as indicated by the first student response quoted above, is that by encouraging students to make connections and engage in what I will call “critical play” (which is like critical reading for videogames), we achieve the primary aims of the humanities in higher education. That is, students start to question their environments and reconsider things they may have taken for granted, and in the process they start to use the thought processes that will help them encounter both new and familiar situations analytically.

Some of this advantage may, with a few generations of establishing and teaching a canon for videogames, eventually fade. That is because currently the greatest strength in teaching videogames the way we would teach literature is in the shock value of actually doing so. Students and educators alike are accustomed to the idea that so-called “Great Works” are suitable for instruction and essay-writing, but are not accustomed to the idea that videogames are—but they may become so. After all, novels were, in the 18th and 19th centuries, generally considered mindless popular culture and beneath analysis or even preservation. Games face much of the same ridicule, but we have found the currents of academic and cultural acceptance running swifter now than they did then.

We are now at the critical moment, when the history of videogames (and game studies) intersects with the history of textual criticism and education—that is, the moment when we will determine the canon of videogames and the methods by which that canon will be taught. This is the time when we will decide the tradition of the future. We have the opportunity not just to revise a canon (as we continually do with drama, poetry, and novels now), but to actually shape a new canon, to craft the narrative of videogame development that will be received by students of what early videogames were and how they developed.

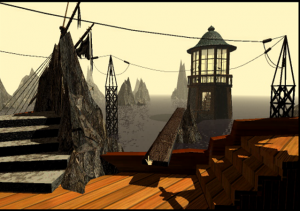

These decisions will be made in a collective movement by individual instructors deciding, more or less independently, what to teach. Each curriculum is an argument. In choosing the subject matter that I did—20th century PC games—I made a claim that this was a valid period and genre distinction, a claim that (remarkably!) my students accepted. By dividing up a course that way, they began to see distinction between PC and console games, between 20th century and 21st century games. In choosing the games that I chose for them to play (Zork, King’s Quest I-III, Space Quest I, Ultima IV, Commander Keen, Myst, Tomb Raider, Descent, Fallout, Pharaoh, and Planescape: Torment), I made a claim about what games and genres were most significant in the narrative of videogame history. I acknowledge that this choice was shaped largely by practical considerations (as such choices will always be), but it was a claim nevertheless, and one that will continue to influence my students’ thinking.

My students were mostly young enough to remember very little of the 20th century, and certainly not to have thought very critically about the events of the 20th century based on experience alone. Thus, for them to understand these games at any level—to be able to play them, to be able to interpret them, to be able to draw cultural connections from them—required that I teach them about historical context. I had to describe technologies that shaped the games that are no longer relevant, and I had to explain market conditions and consumer practices that would help interpret the games. But this is a good thing; such an approach will become more necessary as time goes on, and the origins of videogames fade from recent memory and become a thing of not only nostalgia, but of the distant past. We might as well start now.

It wasn’t hard to impress upon them the historical distance of the games. When I found that materiality and cultural context was becoming a stumbling block for my students’ understanding, I brought in a few choice artifacts: a floppy disk, original packaging from a 1990s PC game, and a CD for comparison (along with my flash drive, which I always have when I teach). This material history is a key approach; no different from an instructor using an image of a medieval manuscript illumination to illustrate the materiality of a pre-modern poem, or showing the original plate illustrations of a 19th century novel to demonstrate the multimodality of Victorian reading practices. It isn’t enough to tell our students that the past was different; we have to show them.

After all, videogames are no longer new. We still sometimes call them “new media,” but that does them an injustice and infantilizes a mature medium. I was teaching several games in my curriculum that are older than I am, and many more that are older than my students. Most histories of videogames right now are deeply tinted by nostalgia, since they tend to be written by people who lived those histories. But we need to start teaching videogames and their history not as something new and novel or as mere memory, but as critical history, fully employing the historian’s and the critic’s modes of constructing the past.

These are actions that will shape the historical narrative of games. The way we teach them and the games we teach—as well as the games we routinely write about in our discussions outside the classroom—will form the canon. And our students will benefit from the canon. If we shape the history well, and if we create a companion canon of critical texts to aid in the interpretation of games, then when we teach games in the classroom, we will also be teaching critical thought and cultural understanding. If we can teach those things, then we have succeeded as educators.

I’ve learn some just right stuff here. Certainly value bookmarking

for revisiting. I surprise how much effort you place to create the sort of fantastic informative web site.

Great article here. Thanks a lot for your inside information.

http://www.justwhatisroku.com

The second quoted comment from one of the “gamer” students is awfully familiar. I could recognize it anywhere.

The biggest reason why I think this comment was mine is because I recall mentioning “AP English” on a couple of occasions only to be reminded that nobody knew what I was talking about. I find I am not everyone else nor is everyone else me.

“I feel the subject matter of the course allows one to be more engaged in writing and is effective in teaching students how to write good papers, the main point of the course.”

Assuming this is mine, I suppose I have a bone to pick with what I’ve written. It is true that the special subject of video games does allow me, personally, to be more engaged in writing but the “gamers” of the classroom were a fairly loud, sometimes rude minority. Many of the students were ones in which games are probably no more engaging than any other form of medium, if not much less so. I’m certain some of those who left the course included those who had no interest in the medium and as such could not find the course nearly as engaging as I found it. Once again, I find I am not everyone else nor is everyone else me.

Furthermore, with regards to “how to write good papers [being] the main point of the course,” the course is much more than that. It also, if not mainly, teaches students how to critically think about a given subject or medium and the implications of an example of it, but in a manner which ideally is largely applicable regardless of subject or medium. Writing good papers is also good, I suppose.

JLR, thank you for commenting. I value student voices in this discussion, and I hope my other readers do too, but because of privacy issues, it’s very hard to represent them fairly (for the record, you self-identified in this conversation). It’s true that what I write in this space is filtered through my own perception; I’m relying heavily on notes I took at the time, and of course any teacher is susceptible to bias in interpreting student behavior–we hope, dearly, that what we are seeing is genuine learning and engagement, even as we’re aware that we might be reading it wrong. You are right about the gamers often trying to take over the course (see “The Problem”), but I also suspect that part of why they did is because they wanted the other students to join them in being dominant in the course.