The Civilization franchise includes some of the games most oft-studied by academics, those here at Play the Past included. One of the most salient features in the representation of history created these games is the “Tech Tree,” the representation of the technological and scientific progress of the player’s civilization over the course of the game. As a game mechanic, the tech tree is so influential as to have become an integral part of strategy games like Civilization, as well as many other games from different genres. Perhaps more than any other mechanic in the game, the tech tree determines who wins and who loses. Indeed, as Kacper Pobłocki (2002) notes, while Civilization and other strategy games often offer multiple victory conditions (conquer the world, reach some scientific achievement, dominate international politics, etc.), the path to achieving these goals is always the same: Climb the tech tree faster than your opponents.

The tech tree manages to reduce and unify the history of every scientific discipline into a single visually satisfying graph. Although it is generally presented in a very matter-of-fact way, this configuration of technological history is far from an objective representation of historical events (even if you believe such things exist). Rather, the tech tree embodies a specific understanding of science, not only by curating a list of the most important milestones within the newly integrated realm of science, but by defining the relationships between these events. As scholars like Gerald Voorhees (2009) have pointed out, these relationships between cause and effect are so strongly defined that many players have reduced the act of play itself to a streamlined algorithm or formula, with the experienced player building and researching certain items on specific turns in order to optimize her returns. Such an approach sounds less like a strategy for a game that tries to simulate the depth and breadth of human history, but rather like classic openings in the much more abstract game of chess. Indeed, many discussions on Civ forums speak in terms of “ideal games” and “solutions” which would seem to simplify the game even further to the level of tic-tac-toe.

I am certainly not the first person to criticize the tech tree. In addition to numerous scholarly critiques, many players and modders have found fault with these tech trees and have even designed their own trees to create what they see as a more accurate view of history. Common themes in these critiques include adding more detail and more technologies to the tree, changing the order in which the technologies appear to more closely mirror their historical appearance, and changing the links between technologies to create more “logical” progressions and prerequisites. Although many of these endeavors are surprisingly well-researched and thought out, the concern I am trying to express is not that the tech tree in Civilization or another game needs to be more accurate. Rather, my point is that the concept of the tech tree itself (at least, in its most common implementations) embodies a technologically deterministic view of history.

In order to clarify my argument, it is helpful to discuss exactly what I mean when I refer to tech trees and technological determinism. As previously mentioned, the tech tree mechanic went on to be used and appropriated by many different games across a number of genres. As the mechanic spread to new kinds of games, the term began to be used more and more loosely. In addition to hierarchies of technoscientific knowledge that the player could develop, such as in the Civilization series, the term “tech tree” has also been applied to organizations of building prerequisites, such as in Shogun: Total War and Heroes of Might and Magic II, and to even more abstract systems, such as the sequence in which materials must be progressively gathered in order to create increasingly complex objects in Minecraft. In essence, nearly any kind of hierarchical system of abilities within a videogame can be colloquially referred to as a “tech tree,” making it expedient for us to develop more precise definition in order to select meaningful objects of analysis.

In the context of this discussion, I use the term “tech tree” to refer to any system of unlockable abilities that are representative of technoscientific advances. Since such systems are usually complex and nuanced, they are most common in (though not exclusive to) turn-based strategy games. Although sometimes present in real-time strategy games, such games more often feature a hybrid system that combines building hierarchies (such as those in Heroes of Might and Magic II) and Civilization-style tech trees. Additionally, real-time strategy games often tend to represent individual military engagements, which have a limited scope both in time and space (a game of Starcraft might be said to represent a number of days, whereas a game of Civilization generally represents around 6000 years). As such, the “researching” of new technology within the game is more representative of requisitioning better equipment from headquarters or of getting an existing technology working in the field than of making a series of scientific breakthroughs in the middle of a battle. Therefore, most of my examples of tech trees will be taken from turn-based strategy games.

Technological Determinism, or the view that technology progresses forward primarily (or according to some, completely) of its own accord, pulling society along with it, is a view that is so prevalent in modern discourse that it is often an unspoken ideological assumption, even in academic writing (Pfaffenberger, 1988). Despite its ubiquity, deterministic views of science and technology are problematic for a number of reasons. Such attitudes complicate the ability of non-experts to engage in discussion with experts while making technology an end in itself, independent of other consequences or considerations (Bijker, 2001). These problems in turn can lead to technocratic thinking, in which power is given to groups of technologically savvy elites at the expense of those who lack technical knowledge and often lack access to that knowledge. Ted Nelson, one of the earliest scholars to examine computer culture, was critical of such thinking as early as the 1970s, referring to technological elites as the “Computer Priesthood” (Nelson, 2003).

Although some scholars defend the commonsensical nature of technological determinism as being merely an intuitive analysis of the way that technology actually operates, many scholars, particularly those within the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS), find the determinist thesis inadequate at best in describing the complex relationship between technology and society. Accordingly, much of the effort within STS has revolved around the development of more robust theories of technoscientific development.

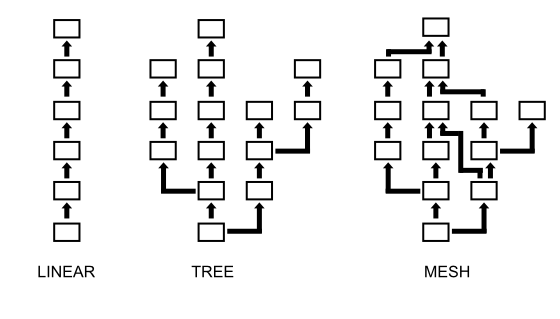

While most scholars have moved away from determinism over the last fifty years or so, it remains deeply ingrained in our cultural mind. Perhaps it should be no surprise then that videogames tend to reproduce deterministic views of technology. Games do, however, reproduce this deterministic view in varying degrees of complexity. The most basic form of this tree is a completely linear model, in which each node (other than start and end nodes) has exactly one prerequisite and is prerequisite for exactly one other node. Games that implement the tech tree in this manner, such as the Apple II game Cosmic Balance II, generally portray science and technology in very abstract terms. In the case of Cosmic Balance II, this is represented by advancing from “Tech Level 1” to “Tech Level 2” and so forth. These linear advances give the player a generic advantage over other players. In games that make use of tech trees as a more tangential mechanic, the tree and its nodes may have a more specific context, such as “Armor Level 1.” Even when these advances are given more thematic titles, such as “Scale Armor” and “Plate Armor,” the mechanical function of these advances is fairly self-explanatory: “Level 2” is better than “Level 1.” When you achieve “Level 3,” it will be better still. Science, in such a model, is a very predictable, cumulative process.

The standard “branching tree” structure from which the tech tree gets its name is both more complex and more common than the simple linear structure. In a branching tree, each node (once again, with the exception of start nodes) has a single prerequisite, but may in turn be the prerequisite for multiple other nodes. Thus, advancing along the tech tree not only grants incremental advantages, but opens up new paths of research to the player. With these multiple paths of research, the mechanical benefits provided by technologies tend to be more nuanced than the simple numerical comparisons possible in the linear model, as well as generally having a far greater number of available technologies. While the in-game advantages provided by individual technologies may be more varied, the progress up the tech tree often remains incremental within individual branches.

More complex games such as Civilization feature an intertwined, mesh-like tech tree, with nodes potentially having multiple prerequisites as well being prerequisites for multiple other nodes. Compared to the examples above, these tech trees have a much more sophisticated model of technology, acknowledging to some extent the influences that different scientific disciplines have on each other. Despite their added complexity, these tech trees still embody many of the aspects of technological determinism found in simpler versions. Players “research technology” in order to achieve predetermined benefits that exist a priori within the game world. The research process simply consists of devoting the necessary amount of time and resources to arrive at a given technological milestone along the path of progress. Indeed, even the concept of “progress” as the march of invention toward some unknown utopia (Smith, 1994) is often reified not as some unknown ideal, but as an actual technology like any other. In Civilization V, the latest game in the Civilization series, this final technology is simply called “Future Technology,” and exists at the convergence of all the other technological paths in the game.

While videogame culture in general tends to be steeped in technological determinism, there are a few games that break out of the mold and do novel things with tech trees (which I hope to address in later posts). These games are the exception to the rule, however, and it seems unlikely that the videogame industry will abandon its deterministic point of view anytime soon. For players, however, the important thing is simply that we are aware of it. The key to being videogame literate, as I see it, is thinking critically about the games we play and not taking them at face value. For videogames, this goes beyond not “believing everything you see on TV,” but also questioning the underlying assumptions on which the mechanics of a game are built. As game designers, I hope that we continue to challenge our own assumptions and try to think of new and interesting ways to implement game mechanics, rather than merely relying on ideas about the world that are half a century out of date.

References

Kacper Pobłocki, (2002). Becoming-state: The bio-cultural imperialism of Sid Meier’s Civilization.

Gerald Voorhees, (2009). I Play Therefore I Am: Sid Meier’s Civilization, Turn-Based Strategy Games and the Cogito.

Bryan Pfaffenberger, (1988). Fetishised objects and humanised nature: towards an anthropology of technology.

Wiebe Bijker, (2001). Understanding technological culture through a constructivist view of science, technology, and society.

Ted Nelson, (1974). Computer Lib/Dream Machines.

Merritt Roe Smith, (1994). Technological Determinism in American Culture.

2 Comments