Videogames have an amazing potential for modeling societal processes. At the same time, videogames also embody the worldview of their creators on a procedural level. As such, it is a rare thing when a game is able to move beyond popular understandings of the world and approach it from a new and interesting direction. As I’ve noted in my previous posts on the tech tree and the portrayal of science in videogames, most games that try to model technoscientific development do so in a very deterministic manner. This isn’t terribly surprising, as technological determinism is still one of the most widespread ways of understanding the relationship between society and technology. In spite of this, there are some games that subvert deterministic understandings of technology, and even some that could be said to approach technology from a more social constructivist perspective.

While I am glad to see game developers experimenting with mechanics that more closely resemble the Social Construction of Technology (and I hope that more developers do in the future), SCOT is not without its criticisms. As Langdon Winner, one of the most outspoken critics of SCOT, points out, although constructivist writing shows how society influences technological development, it does so with “an almost total disregard for the social consequences of technical choice” (Winner, 1993). While SCOT allows us to see the forces behind technological change, as well as the many technical solutions that were not adopted, it has little to offer us in terms of dealing with technology once it has taken shape.

In response to these criticisms, scholars in the field of science and technology studies have offered a up a number of alternative perspectives. Of these, one of the most influential approaches is Actor-Network Theory. Just as SCOT can be seen as a reaction against deterministic theories of technologies, Actor-Network Theory (or ANT) can be seen as a response to SCOT’s indifference toward the influence of technology on society. In ANT, technologies are conceptualized as networks of interconnected “actors” or nodes. These actors can be technical artifacts, knowledge systems, organizations, or individual people. The connections between the nodes represent the ways in which they are able to exert influence upon each other. One of the central assumptions of ANT is that every actor, whether human or non-human, has agency to influence other nodes in the network.

Actor-Network Theory isn’t really a theory in the strictest sense. Theories generally attempt to explain why something happens. Technological determinism explains social change as the result of technological progress. SCOT explains technological development as the result of social influences. On its own, ANT tends to be descriptive, rather than explanatory. Perhaps the most visible result of ANT’s descriptive, rather than theoretical, nature is that there has been endless pedantic arguments about naming conventions. The benefit, however, is that ANT (regardless of what you want to call it) has been adopted by scholars of other disciplines more than perhaps any other theory to come out of Science and Technology Studies. According to John Law (2009):

… it tells stories about “how” relations assemble or don’t. As a form, one of several, of material semiotics, it is better understood as a toolkit for telling interesting stories about, and interfering in, those relations. More profoundly, it is a sensibility to the messy practices of relationality and materiality of the world. Along with this sensibility comes a wariness of the large-scale claims common in social theory: these usually seem too simple.

If we think of Actor-Network Theory as a “sensibility” that we use to tell interesting stories about relationality and materiality, it should come as no surprise that some of the most effective uses of ANT have been as a way to look at history.

Perhaps the clearest example of this sensibility is John Law’s (1987) analysis of Portuguese shipbuilding technology. Many games, such as Age of Empires II, portray such technologies as a series of incremental improvements. Law, however, describes this process as the result of a number of different technologies interacting together as a complex system consisting of basic technological artifacts, such as the development of the magnetic compass, developments in design, such as the mixed-rigging ship, and the creation of new technical knowledge, such as the Portuguese sailors’ discovery of the volta, a route that maximized their use of wind and ocean currents. In Law’s tale, this ship is not a discrete technological artifact, but an emergent object created from wood, cloth, and technical knowledge, held together by the captain and his crew. When the captain’s skill wasn’t enough to hold the ship together, it didn’t take long for it to become a collection of dissociated elements floating in the ocean.

Actor-Network Theory allows us to look at technology in a complex, nuanced way that accounts both for technological influences on society and societal influences on technology. Complexity in ANT is managed by simplification or “blackboxing” (Callon, 1986). In theory, every node in an actor-network can be thought of as a network in itself. It’s not necessary (or indeed, possible) to look at each node in this manner. Thus, if we are not interested in the internal workings of a sub-network, it can be simply considered as a single “black box” within the wider network. For example, the magnetic compass has its own relationship to the cultures that were involved in its creation and adoption, but in the context of Portuguese shipbuilding, it is sufficient to think of the compass as a single node in the technological network. Likewise, the ship which Law so meticulously described might be no more than a single node in the context of Portuguese exploration and expansion.

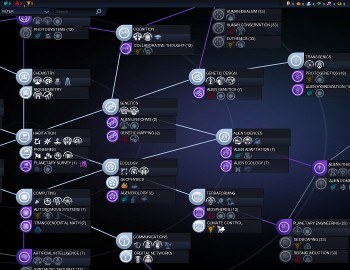

If I were to choose the game that comes closest to a model of technology with an ANT sensibility, I would probably choose Civilization: Beyond Earth, though perhaps not for reason that most players would think. The most obvious departure that Beyond Earth makes from the Civilization series in terms of its technology model is its organization of technologies in a “tech web,” rather than the more traditional tech tree. Although visually distinctive, the actual topology of the tech web differs little from the standard mesh-like tree used in Civilization V. Placing the starting node in the center, rather than the bottom or left-side of the tree as is more common, doesn’t change the actual structure of the tree. In this respect, the only difference between the technologies in Civ V and Beyond Earth is that where the former has a long, narrow tree with seventeen tiers, the latter has a shorter, broader tree, that only has five tiers (if you count “leaf” technologies as their own tier). A far more significant, if visually more subtle, change is that in order to research a technology, the player need only have researched a single connected technology, rather than each technology being dependent upon the prerequisites directly below it. Thus, while Civ V prevented players from jumping more than two or three tiers ahead with its dense mesh of prerequisites, a player in Beyond Earth can make a mad dash for a particular tech while ignoring the rest of the web completely.

While the tech web in Beyond Earth is certainly interesting, it doesn’t necessarily lend itself toward an ANT approach to technology any more than the standard tech tree does. Indeed, since ANT is often used to describe technologies such as information systems and power grids, a common misconception is that Actor-Network Theory is a method for describing networks. Again, as in the example of Portuguese ships, it’s not that ANT describes networks, but that ANT describes all technology as networks. Accordingly, the fact that tech web is visually more similar to our concept of a network doesn’t make it an ANT way of modeling technology.

The aspect of Beyond Earth that gives it an ANT sensibility is the game’s notion of “affinities.” Affinity is the analogue to Civ V’s ideology mechanic, though it operates in a significantly different way. Whereas ideology functioned as a specialized subset of the social policies system and likewise could be purchased with “culture,” affinities are not purchased directly, but develop in response to other choices that the player makes. Researching certain technologies can push a player’s society toward a certain affinity, as can choices made in response to certain in-game events or “quests.” Affinities likewise are able to influence technological development by constraining the technologies available to the player. For example, researching “Alien Evolution” provides no technological benefit to the player unless her faction follows the Harmony affinity, which allows the creation of alien units.

Just as the development of Portuguese ships in Law’s analysis was a product of both technological and social forces, so too are many of the technological artifacts in Beyond Earth. In order for the player to build Neurolabs in her cities, she not only must develop the technological ability to understand human cognition, but foster a society in which the mechanical augmentation of human abilities is encouraged. This is done by researching similar technological solutions, as well as by responding in certain ways to in-game events, for example, welcoming other cybernetic humans into your society, rather than driving them away or removing their mechanical augmentations. Societies can also be guided toward specific affinities by spending culture points on certain virtues, particularly those which are more military-oriented. Thus, many technologies in Beyond Earth are not merely the inevitable result of an unbroken chain of human progress, but rather the intersection of cultural policies, technoscientific research, and physical artifacts.

The three affinities, Purity, Harmony, and Supremacy, are themselves black boxes for more complicated systems of ideologies, cultural attitudes, and social movements. Purity, for example, can be seen as an amalgam of humanism, anthropocentrism, bioconservatism, colonialism, traditionalism, and many other potentially competing ideologies. The choice to abstract these complex social systems as monolithic philosophies makes sense from a design perspective. You don’t want to bury the player with options for what is perhaps already the most foreign mechanic in the game and, indeed, Beyond Earth follows the trend of Civilization V to reduce micromanagement by greatly simplifying some of the game mechanics. Still, of all the black boxes in the game, it is the affinities that I would most like to see opened up.

In an interview before the game’s release, Will Miller and David McDonough, the Co-Lead Designers of the game, hoped that players would interact with the affinity system on both a diegetic and non-diegetic level, alternatively basing their choices on what is best for the citizens of their virtual colonies or what is most likely to make them win.

We’ve found some players always choose an Affinity based on the narrative and moral impact – not everyone wants to outfit his or her people with cybernetic implants. I know a couple of people around the office who find the Purity Affinity almost cult-like, while others see the value of keeping Earth history alive in an alien world. The other type of player will choose the Affinity which best suits his or her current game situation. They’ll play a few dozen turns and try to figure out what’s going to happen in the next hundred.

Some specific choices in the game certainly prompted me to interact with the game on a diegetic level. In response to one quest decision, I decided to make bionic eyes available to my entire population, even though it would have been more strategically beneficial to restrict the technology to my scientists. The choice of affinity itself, however, was far too abstract to evoke the same reaction. Also, since Affinities are not mutually exclusive, it’s not so much a question of “embrace technology” or “protect the environment,” but rather a question of which to focus on first.

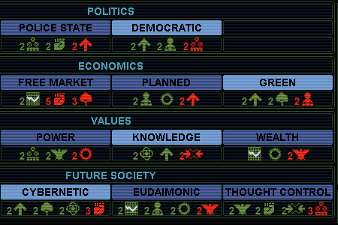

To envision what opening the black box of affinity might look like, we need only look back to Beyond Earth’s spiritual predecessor, Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri. As I noted in my discussion of Civ V’s ideology mechanic, Alpha Centauri deals with ideology in a very complex manner. As the game progresses, the player can make choices about her society’s politics, values, economics, and aspirations for the future. These choices don’t simply lead to one or another kind of society, but influence a number of social factors that significantly shape the way the game is played. A democratic government, for example, gives a faction boosts to its growth and economic efficiency at the cost of making it harder to maintain a large standing military. It is, however, possible for a democratic faction to also place a high cultural value on power, allowing the player to overcome this obstacle while creating other cultural hurdles in the process. I think I might have engaged more with affinity mechanic in Beyond Earth if I had the ability to try and balance Supremacy’s robotics with Harmony’s environmentalism, or if I had to wrestle with embracing Purity’s humanitarianism while rejecting its intolerance.

Beyond Earth may not match the overall complexity of Alpha Centauri in its models of societal processes, but it succeeds in creating new and innovative approaches to modeling technological development. I hope that the designers at Firaxis continue to experiment with ideas like affinity, fleshing them out like they have with so many other game mechanics. I also hope that other designers latch on to these ideas and complicate their own models of technological progress, perhaps realizing the potential that videogames have to illustrate complex perspectives on society and technology that transcend simple determinism.

References

Langdon Winner, (1993). Upon opening the black box and finding it empty: Social constructivism and the philosophy of technology.

John Law, (2009). Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics.

John Law, (1987). Technology and heterogeneous engineering: The case of Portuguese expansion.

Michel Callon, (1986). The sociology of an actor-network: The case of the electric vehicle.

Thanks for this post! It both makes me excited to try and find some time to play Beyond Earth and scratches the itch of one of my favorite games topics. It continues to make a funny kind of sense to me that their “play the future in space” games have ended up offering better models of how history works then their play the past games. I think we just have a much clearer sense of how contingent and fraught technologies are in the present and looking forward than we do in looking back at what seems to have inevitably lead us to our present situation.

I would be very curious to know how Beyond Earth is put together. If it is anything like how they approached remaking colonization, there is a chance that it may be built as a Mod to the existing application. If that is the case, there is a good chance that there will be (more or less) human readable files, likely in Python and XML that one could poke around in to try and see if some of the underlaying logic of the “affinities” stuff can be read at the level of the source.

I agree. It’s no coincidence that of the games that I’ve talked about that subvert tech determinism, most have been science-fiction themed rather than historically themed. “Playing the Future” definitely changes the way we try and model society. On the one hand, like you said, it tends to free us somewhat from the deterministic, Whiggish way we tend to think of our own history, but at the same time, it also makes it harder to connect with the game on a diegetic level. It’s a bit easier to ascribe cultural meaning to the game when the enemy’s guns taking out your knights than it is when it’s merely the enemy’s giant robot mowing down your different kind of giant robot.

As for the code itself, the SDK lets you access a lot of XML and Lua files for modding purposes, so you can kind of poke around and see all the things that units and buildings do (or could potentially do) in the current version of the game. I talked about it at length in my Software Archeology post, but what I’d really like to be able to poke through is the source code itself, which has parts of its codebase that go back not just to Civ V, but to the original Civilization. It would be neat to see how closely the Affinity mechanic is related to the Ideology mechanic in Brave New World and whether or not they share any common code. For now, though, I guess I’ll just have to be content to putter around in the modding SDK.