We live our lives immersed in numerous complex systems – systems of meaning, economic systems, information networks, large socio-technical systems, and so forth. One of the things that make videogames interesting is that they allow us to momentarily step into a different set of systems and play with them. We often refer to this process as stepping into a Virtual World, which is a useful way of looking not just at the the persistent online spaces in games like World of Warcraft, but at games and software in a much broader sense, as well. Stepping into a virtual world allows us to experiment with different systems or even simulated versions of real-world systems. For example, José Zagal (2009) has noted that games can make moral demands of players by encouraging them to reflect on moral dilemmas, such as those found in the Ultima IV or Manhunt. In a previous post, I discussed how playing games like gyān chaupar (better known in the West as Snakes and Ladders) allow us to understand the ethical and moral reasoning of other cultures and groups.

While this aspect of videogames gives designers a great deal of artistic freedom, it simultaneously poses a significant challenge. More often than not, game developers unintentionally build their virtual worlds to reflect their own ideological perspectives on the real world (Bogost, 2006). When creating historical games, this often leads to a certain amount of presentism at the procedural level. For example, as Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter (2009) discuss in their book Games of Empire, most “neomedieval” worlds in games like World of Warcraft and EverQuest are created with modern market capitalism as an integral element, despite the fact that such systems are anachronistic. In most cases, this is not a deliberate design decision – capitalism is so ingrained in Western culture that we have a hard time thinking of any other way to do things. This makes the task of explicitly designing ideology for a game rather challenging.

Implementing an explicit ethical system into a videogame is not uncommon. These systems can take many forms, from the light side vs dark side mechanic common in many Star Wars games to the karma mechanic in the Fallout series to the sin mechanic in Princess Maker 2. Having an “ethics mechanic” does not, however, mean that the player will necessarily engage in the kind of moral reflection that Zagal discusses. Star Wars games, for example, feature many points where the player must make a moral choice, but there is never a dilemma because some choices are explicitly good while others are explicitly bad. The choice for the player is not a question of how to resolve a complex dilemma, but rather a question of which narrative she wishes the game to follow.

Looking at these systems from a design perspective, there is another commonality that most of them share. Although the in-game effects of these ethics systems can be mundane or supernatural, the algorithms for classifying player actions generally reflect broadly accepted social mores. In other words, even though performing good actions in a game might give you Jedi powers, the “good” decision for a Jedi is probably also a good decision for the player in her day-to-day life.

It is, however, possible and often desirable to design ethical systems that differ from those of the player, creating the opportunity for the ethical reflection similar to the kind players experience when faced with moral dilemmas. The difficulty is that if this ethical system is also different from that of the developers, it can be difficult to model authentically, leaving a system that is confusing to the player.

So how do you design an ethical system in a historical game?

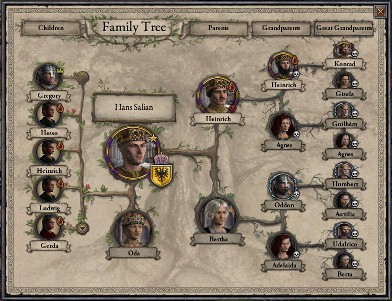

A good example of how to approach this problem is the game Crusader Kings II, a strategy game set in Medieval Europe. Rather than a traditional strategy game about armies and invasions, Crusader Kings II is more a game about interpersonal relationships. Instead of controlling an abstract country as you would in Civilization, you control a noble house, with the current ruling member as the active character. Every character has a multitude of characteristics and statistics that combine to influence his relationships with every member of his family, every vassal in his court, and every other person in Europe.

At first glance, it would seem that mechanics for moral judgment are already included among these various tallies. Every character has a “piety” rating that goes up when he performs virtuous acts, not unlike the various mechanics previously mentioned. Additionally, virtues and vices are listed on the various character sheets, with the seven deadly sins being marked in bright red and their opposing virtues marked in green. To someone just picking up the game for the first time, it might seem that the game has a very well-defined and unambiguous framework for working out the morality of in-game decisions.

While such a statement might be nominally true, the procedural implementation of these moral principles is considerably more ambiguous. As the player becomes more familiar with the way that the game’s mechanics work, she might notice that while some sins certainly have negative consequences, such as sloth, which makes you a bit worse at everything, most sins are a trade off, such as being wroth, which improves your martial ability at the expense of a slight reduction in your skill at diplomacy and intrigue. Other deadly sins, such as pride, are entirely beneficial in terms of game mechanics. Likewise, virtues such as humility tend to be less desirable for players to develop in their characters.

In contrast to values such as modern capitalism that tend to creep into medieval games unintentionally, the values in Crusader Kings were very deliberately designed. According to Henrik Fahraeus, the lead designer:

I wanted to have the deadly sins and heavenly virtues because they were so ingrained in medieval Christian European thinking. However, when considering which effects these traits should have, it felt like many of the sins, for example, should have some positive effects as well. For example, a lustful character would reasonably be more fertile, which is a good thing. As for pride, I thought it would mostly be a beneficial quality in rulers, the state on their souls notwithstanding… I also like the moral ambiguity of wanting to foster certain sinful traits despite the views of the Church.

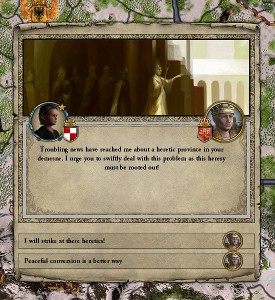

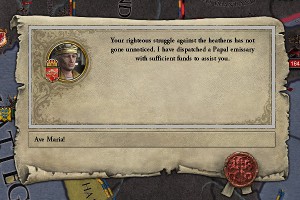

Piety might correlate with ethical decision making more than other mechanics, but even pious decisions are not necessarily moral or desirable. For example, chastising your wife for reading too much romantic poetry is rewarded as a pious act in-game. While such an action probably doesn’t sit well with the player’s 21st century sensibilities, it’s not really portrayed as a completely appropriate in-game choice, either, as the choice will create ill feelings between the ruler and his wife. In a game where familial relations are as important as international treaties, such choices can have dire consequences. In practice, piety is less about measuring a character’s internal moral compass and more about accumulating clout with his religious leaders. By taking actions that impress the clergy, regardless of whether they seem ethical or not, a ruler can build up a positive balance of piety that he can later trade for favors like divorces and excommunications.

To say that the constant trade offs in Crusader Kings encourage the player to adopt a Machiavellian approach to politics wouldn’t be entirely unfair. The game presents a very empirical and pragmatic view of social interactions, in contrast to the more idealized versions we see in games like Civilization. While wrath may be sinful, its practical application in warfare is appropriate, if not a bit cynical. At the same time, the game’s mechanics shouldn’t be simplified to merely encouraging the player to play as a self-interested tyrant, due to the fact that while the player can only control a single character, she actually plays as a dynasty. When one character dies, the player takes control of his heir (who is occasionally the one who just secretly murdered your previous character). As such, the game rewards the player not for looking after her own interests, but after the interests of her whole family. Being a paragon of virtue can be useful in some circumstances, but benevolence and self-sacrifice toward kinsmen is always a sound long-term strategy.

The values that a good Crusader Kings player is encouraged to adopt within the game world are essentially the values of the European feudal system. Strength and ambition are rewarded (though deference to the Church can be a valuable asset as well), but family should always be first and foremost. Thus, by stepping into the moral system of the characters she controls, the player is better able to succeed within the game world.

From a design perspective, Crusader Kings II demonstrates two important principles in avoiding the kind of presentism that is common in historical games. First, the designers were very conscious of the way that morals and ethics were discussed in the period in question, for example, the prominence of the Seven Deadly Sins in medieval christian culture. At the same time, they did not allow this discourse to wholly shape the game systems, turning the game into a familiar idealized narrative of chivalry. Sins are not simple dark side points that turn your character into an evil king. Rather, they are complex personality traits that have a number of effects upon the character’s relationship with the Church and with other characters.

The end result is a system that is deep and engaging. This is not to say that the system of ethics the player engages with in Crusader Kings II is necessarily the most historically correct or that other medieval games should try to adopt it. You could certainly make an argument for a different way in which the concepts of sin and virtue influenced the actions of noble dynasties, but that’s kind of the point. The game is a good argument. By immersing herself in this virtual world, the player is able to play within this ethical system, contrasting it with modern social mores and challenging traditional “knight in shining armor” narratives about medieval life. If we want our players to have similarly deep experiences with our game systems, we need to be diligent in exploring historical context while still remaining critical of our source material. We need to embrace nuance and create systems that function as a compelling argument. Doing so doesn’t just make for good game design, it makes for good history.

References

Ian Bogost, (2006). Videogames and Ideological Frames.

Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter, (2009). Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games.

José Zagal, (2009). Ethically Notable Videogames: Moral Dilemmas and Gameplay.

The beauty of the Crusader Kings method – attaching non-binary gameplay benefits to your game’s ethical system – is that it’s more flexible for future expansion. Playing as a Muslim, your values are quite different: you spend a lot of your time scheming to keep your family in line instead of advancing their success, and you accumulate piety mainly to justify waging war, rather than to reap social/financial rewards.

I would agree that strict good vs bad dichotomies are definitely hard to expand upon. Not only would it be really difficult to add a third path to Knights of the Old Republic besides the standard Jedi and Sith options, I have a hard time imagining how something like that could be introduced in a way that would be coherent for the player.

In contrast, I would say Crusader Kings has done an excellent job at making small additions in order to make their existing mechanics work for other cultures. In fairness, though, I wouldn’t say that the design of Islam in the expansion favors more scheming than Christianity, just different kinds. For example, it can be incredibly difficult for a Catholic king to make an exceptional son his heir if he has any older siblings. The less intricate Muslim succession laws allow a ruler to essentially select the most suitable male heir, though in return, he has to manage the image of his house lest his subjects think his rule too decadent.