Science and media have a complicated relationship. Film and television crews regularly hire science consultants both to improve the realism of their productions and to give themselves an air of authority and respectability. Scientists also have a vested interest in being involved in such productions. Since most people invest more time in consuming entertainment than reading conference proceedings and monographs, media depictions are crucial in shaping public attitudes and understandings of science. By attempting to influence the production of a film, for instance, scientists have the potential to correct common misconceptions about scientific facts, increase public support for their field of research, and even attempt to popularize their own theories, as paleontologist Jack Horner was able to do with his then controversial hypotheses about warm-blooded, bird-like dinosaurs in the movie Jurassic Park (Kirby 2011).

Perhaps more visible than the contributions of scientists to the production of media are the critiques of media for their scientific inaccuracies. Many scientists and academics have invested a considerable amount of time calling attention to scientific errors in media, perhaps best exemplified in an argument that took place in the prestigious journal Nature about whether or not the television show The X-Files was warping the public’s perception of science (Durant, 1998).

While media can potentially erode people’s confidence in scientific experts and turn them toward discredited theories and pseudoscience, the pendulum can also swing the opposite direction. By portraying scientists as the “custodians of genuine knowledge” (Durant, 1998), media can perpetuate the idea of the scientist as a heroic, infallible genius, and any detractors as merely superstitious villains — an attitude that can be just as problematic. Perhaps the most well-known example of this is the alleged CSI effect, in which jurors who watch crime dramas have unrealistic expectations of forensic evidence or unwarranted confidence in unproven or even fictional forensic procedures (Stephens, 2006). Since the portrayal of science in media has such great potential for shaping public opinion and it is easy to go too far to either extreme, science communicators have spent a great deal of time discussing how science is depicted in books, television, film, and advertising. Surprisingly, however, very little seems to have been written on the way that science is dealt with in games.

This past summer, I had the opportunity to present some of my research at the Foundations of Digital Games conference. Many of the ideas I dealt with in my presentation I have already discussed in some detail here on Play the Past. The main point of my argument, however, was that the portrayal of science in videogames is significant in shaping public understanding of science and should be examined alongside television and film. In fact, there are a number of reasons that games like https://www.666casino.com/sv/games/slots/ could be more important to the ways that we understand science and technology than other forms of media.

Most scientists understand that television and films often make concessions in scientific accuracy for aesthetic purposes. Minor factual inaccuracies, such as misuse of technical jargon, may irritate experts, but rarely provoke a strong response. Even major scientific errors can be forgiven if they are blatant enough that the audience sees them as fantastic. The most impassioned responses from the scientific community occur when films start drifting into the realms of pseudoscience — giving credence to disproven theories and dubious methods. Despite their often persnickety attitude toward factual details, scientists are far less concerned with errors that might impact science literacy (believing there to be sound in space, lasers moving visibly slower than the speed of light, etc.) than they are with errors that could potentially impact cultural meanings of science (Kirby, 2011). Thus, scientists weren’t outraged at The X-Files because it featured fantastic monsters (which is not uncommon in a television show), but because it portrayed folklore and conspiracy theories as being better at describing the real world than tested scientific approaches.

As science communication scholar David Kirby (2008) points out, the “science” that we are exposed to in film and other media is not just the factual minutiae that are easy to point out, but what he calls the “systems of science.” These include the relations between individual scientists, scientific instruments, industrial and state apparatuses, education systems, and much more. He notes:

In the end, scholarship on science and cinema should be aimed at understanding how the systems of science are depicted in cinema, how these depictions have developed over time, how contemporary film-making practices contribute to these depictions and how these depictions affect the real world systems of science.

Kirby’s focus on the underlying systems that underpin scientific endeavors is not just applicable to the portrayal of science in film, but to the ways science is dealt with in media more broadly. Among these, however, I believe that videogames deserve special attention. In film and television, the systems of science tend to be shown primarily as background elements or subtle details — certain types of instruments on a table, the tone of conversation between a scientist and a bureaucrat. The systems are there merely to support the development of the characters and their actions on screen. In games, however, systems often take center stage, with characters such as “science advisors” often appearing merely to provide atmosphere to the systems themselves.

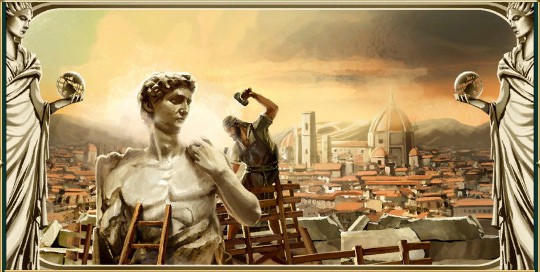

As I have mentioned in previous posts, depictions of scientific development in videogames are often deterministic, portraying science as a relatively linear and cumulative endeavor, beginning at some given point antiquity and ever progressing toward some inevitable future goal. Deterministic views of science and technology can be problematic, particularly when held by individuals involved in technological development or tech policy making. Even outside of such positions of power, however, notions that modern Western technological achievements were natural and inevitable can distort cultural understandings of non-Western cultures. As Michael Adas notes in his book, Machines as the Measure of Men, material culture, especially that related to science and technology, has long been used by Europeans as a measure of development for non-Western cultures (Adas, 1989). If technological development is assumed to be linear and deterministic, it becomes possible to rank cultures based upon their relative position within this continuum.

Historically, this ranking of cultures in terms of science and technology has had a great impact on European attitudes toward the rest of the world, as well as on the ideology of Western imperialism. As Adas notes, even cultures like China, which were praised by many European writers, were later criticized for their perceived backwardness in science and technology. This contributed to the justification to remake the country along Western ideals (Adas, 1989).

Mechanics like the tech tree takes this general scale of cultural advancement and quantifies it into a rubric of discrete technological steps. There is no need for the likes of Voltaire to debate the merits of one culture over another, because such discrepancies are already noted and tallied within the game. Once the player of Civilization encounters another nation, it is usually a fairly simple task to discover if the new culture is two technologies ahead or five technologies behind. In fact, throughout the game, “historians” occasionally appear to write their seminal works. Although the framing fiction of these events implies an actual person writing a lengthy book, the actual mechanic merely shows the player a list of the rankings of different nations within the game, sorted by number of technologies, total population, or some other metric.

With their ability to model the systems of science in a much more direct manner than many other media, videogames have the potential to shape public perceptions of science and technology much more than we give them credit for. Anecdotal observations suggest that games like Civilization play a significant role in the way many people understand technological development. It’s not uncommon, in my experience, at least, to hear people casually refer to tech trees when talking about real-world technology, especially when comparing countries or groups to one another. Of course, my first-hand experience is far from representative, as I spend a disproportionate amount of time discussing videogames, but it would be interesting to see more research about how much the general public’s understanding of technological development is actually informed by games like Civ.

Although many scientists view quibbling over the details of science in entertainment media to be a waste of their valuable time, the impact of a well-made film should not be understated. The China Syndrome, a film about a fictional nuclear accident, was able to shape the dominant narrative of nuclear energy concerns in the late 1970s due to effective input from scientists during production. The portrayal was so realistic that when the Three Mile Island accident occurred just days after the film’s release, viewers found the real-life coverage eerily similar to the film narrative (Kirby, 2011). Although videogames don’t yet have this level of cooperation between developers and scientists (although educational games and many other serious games are a notable exception), there is a great deal of potential benefit in such a collaboration, both for game developers and for scientists.

References

Michael Adas, (1989). Machines as the Measure of Men: Science, Technology, and Ideologies of Western Dominance.

John Durant, (1998). Wacky, weird and scientifically illiterate.

David Kirby, (2011). Lab Coats in Hollywood: Science, Scientists, and Cinema.

David Kirby, (2008). Cinematic Science.

Sheila Stephens, (2006). CSI effect on real crime labs.