This interview is the part two of a three-part series on teaching historical game studies at the undergraduate level, and part one of our interview with researcher Julien Bazile. In this interview, we discuss with Julien his role in co-designing the HST 287 “History, video games and gamification” course, offered in the fall 2019 semester at the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec, Canada.

Julien Bazile is a PhD student, contract researcher (University of Lorraine) and teaching assistant (Université de Sherbrooke). At the crossroads between historiography and game studies, his doctoral research focuses on the design of video games in terms of historical authorship, and the mobilization of historical sources in the development process in Assassin’s Creed games.

N.B. The interview that follows was conducted in French, then transcribed and translated into English by the interviewer. For our interview with Julien’s collaborator Thierry Robert, click here. You can also read part 2 of our interview with Julien by clicking on this link.

Julien Bazile interview

Describe to me your career as a researcher … and as a player! How did you come to U Sherbrooke?

I was born in 1992, my first contact with video games dates from the late 1990s. My first console was a Super NES, but I wasn’t much of a “console gamer” as a kid. I come to video games at a time when games are starting to be considered as legitimate cultural objects, and not just entertainment – it was towards the end of the 1990s that the university study of video games really began to take off.

So, I came of age during this period. I was more oriented toward computer games – and computers have been the platform of choice, we know, for historical strategy games, management games, games that are slower paced, a little more reflexive and contemplative. That said, video games did not occupy the center of my life, they mixed with other passions and interests, music, literature, and film. Games were just one way to “consume” history, or the presentation of history, alongside other media. But history themes always scored high in my evaluation of games. As soon as a title dealt with history – whether popular or not – the game could be interest to me.

At university, I studied history. I followed a history cursus all the way to the Ph.D. level, and have a BA and MA in history. I chose the research option over teaching. My research dissertation did not focus on video games: I studied a learned society of doctors in the nineteenth century in the region I come from. So, nothing to do with games. I’ve also always had, throughout my academic career in the “historical sciences”, an interest in historiography, i.e. the theory of historical discourse. The big difference between history that is taught in high school and the history I was doing at university-level is that at the university we were taught history as critical discourse – that is, history does not fall from the sky, “here’s what happened”, “here’s how it happened”, etc. Rather, we were told that there were different authors, schools of thought, and approaches. Much more attention was paid to form, and therefore the “production” of history at the university.

I always thought it would be interesting to somehow link my two centers of interest. As it turns out, in the department that was next to mine, the Department of Information Science and Communication at the Université de Lorraine, with a researcher, Sebastien Genvo, who was the first in France to have produced a PhD dissertation on video games. So, I approached him at that time, that’s how I started the possibility of doing a thesis, working on the interface between video games and history, and not just doing a thesis in information and communication sciences. Because there is a need for adequate funding for any major thesis project, I would need to apply for a doctoral contract. I thought of a “cotutelle” (joint PhD program), and I contacted U Sherbrooke to initiate the process.

I contacted Sherbrooke because I really wanted to work on Assassin’s Creed in general, and two AC opuses in particular. I also wanted to focus exclusively on a thesis in history, but this was not possible. With the video game component in information and communication sciences, I wanted to intervene with the disciplinary approach of history. Historiography is really my thing: the study of sources, of historical writing, and the historian’s perspective. That’s why I contacted Jean-Pierre Le Glaunec, who is my director of history at the University of Sherbrooke. It happened in an accidental way: I learned that – this was in 2013-2013, so, Ubisoft had just published Assassin’s Creed: Freedom Cry, which centred on slavery, and resistance to slavery, etc. – Jean-Pierre Le Glaunec had been contacted by the Ubisoft Montreal production team, and this had been front page news on the Université de Sherbrooke website. Next to this news item was an announcement about a new course on offer: it was the first occurrence of the course now given by Thierry Robert, HST 287 “History, video games and gamification”. So that’s how I arrived at the University of Sherbrooke.

Thierry Robert recalled for me the circumstances that led to the creation of the HST 287 course in 2014, and now in 2019 as part of the course offering of the history at U Sherbrooke. How did you get involved with HST 287?

In the history department of the University of Sherbrooke, I wanted to speak about video games and the representation of history. There are course loads that are proposed within departments every year, and I knew they were planning to offer once more the “History, video games and gamification” course that was originally given back in 2014. I applied as a teaching candidate, but the department gives precedence to the person who has already given a course for the priority of the teaching tasks. Given that he was involved in the creation and teaching of the first version of the course, Thierry is now teaching the course in 2019. I contacted Thierry to indicate my interest in participating in the course. He got back to me, and since I blend historiography and video games at University of Sherbrooke, he proposed to invite me as a guest speaker.

So, you taught a session in HST 287 during the current semester?

Thierry and I have long discussed the form and content of the HST 287 course. It is a course that is still in its early stages. Being that this is its second occurrence, we discuss a lot what to include and exclude in the course. I have discussed with Thierry the different ways in which this course could be designed, and how I could contribute. In my first classroom intervention, I provided a general introduction to “Historical Game Studies” and proposed a number of concepts to help think games and gameplay in general, i.e. how we analyze games, what critical perspectives to employ, and how one can analyze representations of history in games.

So, this is how I’ve provided some input. I made a second intervention in November, where I talked about sources in the design process, and how to critically examine game content that appears in a finished product. The idea here is to go have a look “behind the scenes”. I have tried to bring theoretical perspectives and also my knowledge of the milieu of production, concrete elements that can be worked with.

Finally, I have also extensively reviewed with Thierry issues around the lesson plan, since I plan also to submit my candidacy for teaching HST 287 in 2020.

During your class lecture, how did you present concepts in “Historical Game Studies”, which are fairly new concepts? Thierry told me that there is a section of the course that deals with the history of video games. In your specific intervention, how do you present concepts to an audience that does not have previous exposure to these concepts? Considering the volume of critical literature around video games that exists now, how do you approach teaching new concepts to students?

It must be emphasized that HST 287 is an undergraduate course. History students discover their faculty, and learn to approach history as critical body of knowledge, as “formed discourse”, etc. So, we worked backward from this key constraint. I myself arrive in the second part of the course, after Thierry has presented the history of leisure, and video games. Here, I presented video games as a medium for historical discourse and looked at issues surrounding the representation of history in video games. I construct “bridges” between cultural criticism and video games: students already know the different ways that we can criticize a text, for example, or criticize a film. In film studies you learn to critique shot construction, and the language of the camera, etc. in the text there are the figures of speech, narrative construction, in historiography, what you choose to include or exclude as sources, etc.

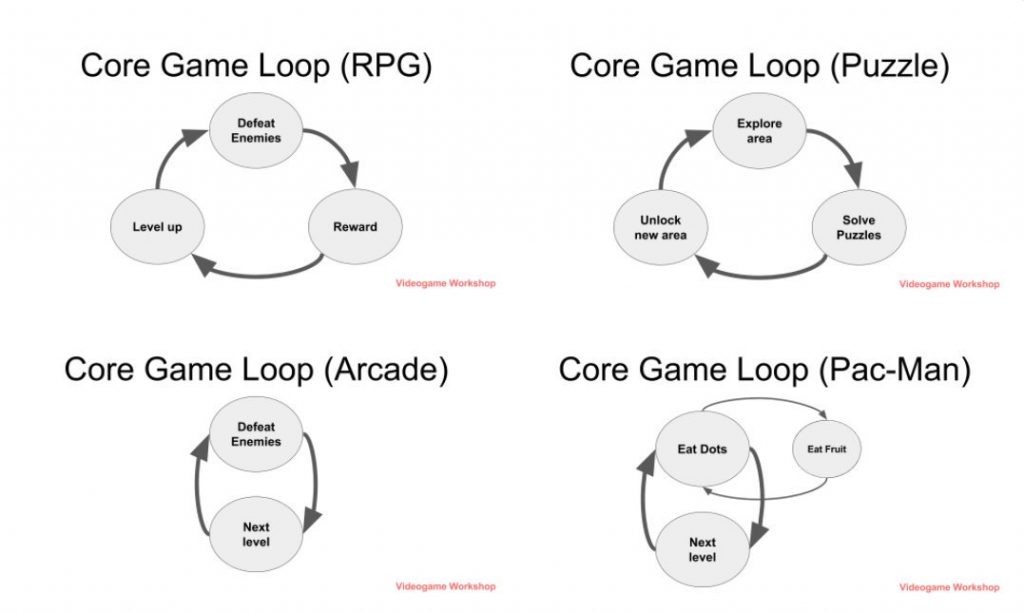

So, I try to bring these considerations to the table, and get students to focus on how the form of a discourse (or the properties of a medium) participates in its content. I’m also looking at the different formal properties of games. So, for example, how can some gaming mechanics already carry with them a certain discourse, how do combat mechanics, or mechanism for the accumulation of resources, a mechanism of space exploration, etc. already carry certain meanings. With Triple-A games, for example, that have extensive worlds with detailed models and that reference many historical sources and a lot of content, images and multimedia, etc. how do they bring a different level of historical grain – and therefore historical discourse – than a smaller production.

So, my classroom intervention really focused on issues of form, and me telling the students “let’s observe the form, and the concepts that I am going to give you will serve you to think about form”. For example, I proposed some tools of analysis of the playability, by taking again a theorist who is called Thomas Malaby, who proposed a grid for analyzing gameplay that references the notion of “contingency”. Contingency being what, in a game, could produce a different outcome. Crossing gameplay and historiography, the player / critic asks whether she can or cannot “do things differently”. If she cannot, we have the idea of a past involving deeper structures, that may not change or change being difficult. On the other hand, if we redo a sequence and come up with different outcomes, this produces another understanding of the past.

So, I help students make links between gameplay concepts, game design and game studies, adding to this critical concepts of historical discourse. For example, I mentioned the notion of counterfactual history, telling students that there is a historical approach that is quite difficult to transcribe in writing, centered around the question: “what are the turning points in history?”, i.e. what caused novelty or change to occur? Also, what can we consider as a deeper change? Finally, how we can express this in game format? What, in a game, might represent a historical “turning point”? How is this played out around player / actor choices, and the consequences of these choices? How does a game express historical facts that involve the player, as an imagined historical actor? Or, conversely, as someone who will remain a spectator or consumer of historical narrative…

For me, it’s a question of trying to take these concepts to articulate relations between history and historiography, and game design. My first intervention was thus more focused on theoretical side of things. The second looked at the more practical aspects of historical game design. I spoke more about the sources used in my research, the limits of these sources, of the extent of my research in the context of production, to show examples of what a developer can do with these concepts.

So, if I understand correctly, you try to blend two major disciplinary currents, each having their core concepts, i.e. the study of video games as a cultural form, and the critical analysis of the historical writing. To see how these discourses “cross” in the different video game genres, i.e. how game mechanics and different types of games can be considered different forms of historical discourse.

That’s correct.

What pedagogical approach would you consider using to teach the history of video games, and the treatment of historical narrative in video games? Especially for an introductory undergraduate course that can accommodate both gaming enthusiasts and non-gamers as students?

As you hint at, there is a basic problem of literacy that arises. We can assume for the most part that gaming culture is widespread among (relatively) young audiences. However, I believe that it’s important to build a common vocabulary, and that is why I mostly focused on providing conceptual tools in my first contribution. Not to contradict what was already given by Thierry, by the way. But simply to give my opinion “this is how I understand by the concept of playability, that’s what playability can mean to me. Here’s how I look at game mechanics, and the way I reference them, etc.”

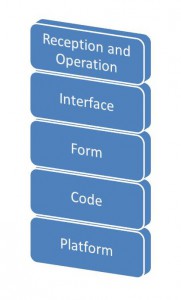

The two “core pillars” of the course are: 1. the history of video games, and 2. representations of history in video games. I think that when you teach the history of video games, especially since it’s a course open to other disciplines and is constructed from an interdisciplinary perspective, you have to think of video games as a complex subject. You have to do a little bit of “hard philosophy”, and ask: what is play, what is a “game”, how is a game different from a competition, or a puzzle? So, there is a little bit of semantics and philosophy of games involved. You also need to cover some history of recreation, a history of industrial relations, since video games are big business. Then there’s a history of techniques, platforms and technologies. After that there are also artistic considerations, so the history of the arts. Basically, there are many angles and approaches involved in teaching this subject.

I think that the crux of this course, from a pedagogical point of view, is that it is an undergraduate course. It serves as an introduction to the university study of video games. There are plenty of angles under which we can study video games, as already mentioned. In future iterations, I could just as easily focus on a history of techniques, historical of hobbies, history as media or the arts. That said, the idea here is to introduce topics and approaches, but not go too far in any specific direction. As a student, I did not have, for my part, any initial training in game studies, at the bachelor’s level. In my case, I finally got to dig into the literature in my first year of doctoral studies. In fact, there is still no bachelor’s degree that I know of in France in game studies. This may start to change a little bit, now there is a program that opened in my university just last year, in a master’s program, in games and digital media. But there is overall very little initial training available in the academic world. So this is the first step involved – this initial training in concepts and critical literature – so we can introduce the idea that video games are a complex object, that can be approached from many angles of critical study.

On the treatment of history in video games, it seems relevant to reuse tools and critical approaches are already in use in other “studies”. For example, historical novels, or historical movies. While keeping an eye to the specificity of games, point out to students that there are, for example, filmic tropes and techniques used in video games that deserve to be analyzed. So, begin with general critical concepts, look at borrowings from other media, i.e. “here, you will make connections with cinema, literature, etc.”. Then, understand that what is specific games, compared to everything else, i.e. the interactivity, immersion, player choices, rules and the mechanics, and so on. So, as it is done in many introductory courses, start from what some level of generality, find linkages, then arrive at the specifics of games as media.

These would be some of the pedagogical principles I would use – should I be called to teach this course – with reference to the two “core pillars” already mentioned. I’m not saying we absolutely have to keep both – the history of games, and historical representation in games. But if both approaches are maintained, I would follow along the lines of what Thierry has built. Note that it is a fairly complex task, to use these two approaches, and make them complementary.

Thierry told me that he is trying to bridge the gap between practice and theory, with a student assignment, which involves adapting historical content into game mechanics. How do you see the practical work assigned to your students in your formula of the course?

I would say what is important is to stay focused on the objective of this course, which is that it is an introduction in which we try to teach essential notions of media and ludic literacy. Add to this: how play (and game mechanics) produce meaning, especially with reference to the representation of history in games.

This raises the obvious issue of direct access to reference materials. I note that if gaming literacy involves the use of a controller and the experience of a game interface to experience game playability, the skill of reading texts is much more prevalent in the population. In any case, this concept of “game literacy” involves more than simply learning to operate a game. You need to learn to criticize a game without player skill intervening too much, and make sure the most skilled players don’t gain undue advantage others who have less skill, or time to devote to games. Of course, you have to have access to hardware, and a library of games for consoles and computers. Yes, we can ask students to watch “Let’s Play” videos so that they can critique a game. That’s one angle. But as we all know, watching someone playing a game, and playing one oneself are not the same thing.

As far as assignments go, I would choose one that involves a platform to which everyone has access to, a computer. And if possible, I’d select a simple game in both mechanics and skill, but one that also allows for a certain complexity and a wealth of interpretation. So, I would not ask my students to get a PS4 and play the latest “Assassin’s Creed”. Rather, I’d go with a smaller indie game.

Another interesting approach revolves around the idea of “creating game mechanics”. What I would like to do in years to come would be to ask students to create a small game. Perhaps for master’s students enrolled in more advanced courses, ask them to create a small game. With user-friendly game creation software, create a game with simple mechanics, on which will then be evaluated, and graded. Creating a game can be very complex, and it involves a certain level of risk. But the happy medium, which I think Thierry has found, is to say: “ok, so now you are at the design phase, you’re a game designer…” Either I can impose a period or topic or leave them the choice. We choose a period, and the sources we have at our disposal. Then we start from the question: “How are you going to adapt sources to game mechanics?”

With this exercise, students have to justify their choice of a particular game mechanic, and the design choices made in “gamifying” a historical topic. What will be the goal of my game, what will the rules be? What will be the central focus of the game? Will the game play out an evolution in time, or not? And what characterwill my player play?

This would be a good place to bring in some new theoretical perspectives, too. We could follow a template-based design approach. For example, the template on which Jeremiah McCall is working, to design player goals and objectives, or the concept of “historical problem spaces“. This kind of template would be relevant for students to fill in. Not just for the purposes of critiquing a game, but from a design perspective, i.e. what objectives would you assign, why, what would the agent be controlled, what would be the different mechanics of the game, etc.? This seems to me an interesting approach, which combines written work produced by students – which makes the exercise accessible to everyone, and always useful for grading – and at the same time adds the specificity of the game as a “medium”. In short, produce something, not just criticize something already out there. And see how we can bring in a critical perspective in the process of creating a historical game.

End of Part 1 of our interview with Julien Bazile. Stay tuned for Part 2, coming next week.