Joel is a MA student in the Communication and Culture program at York University in Toronto, where he plans to research the empathetic potentials of digital roleplaying. If he’s not playing and dissecting a strategy sim or RPG, then the chances are he’s off driving someone crazy by gushing about his favourite games. More of his writing can be found at www.thethirdmedium.com.

What do you do with a kid who underperforms at school and plays too many videogames?

From the totally unbiased perspective of someone who loved videogames and wasn’t always a standout student, I say this: give ’em the right game.

My History

For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved everything historical—or rather, almost everything historical. If you brought twelve-year-old me to a model fur trading post at the Fort Edmonton heritage park in my hometown, I’d want to feel the furs, ask how much they went for, and learn which Indigenous nations traded with which Europeans. But at school, I’d usually spend the hours of history lessons daydreaming or sneakily pulling up games on my laptop. Ask me to draw up a timeline of the fur trade on a test, and I’d drop marks from the year 1670 to 1867 One possible explanation for the gap between my enthusiasm for history and my disinterest in its classroom form is that I preferred learning in ways that didn’t revolve around reading—my brain just wasn’t wired for it. But having recently completed a BA in English Literature, I’m not convinced that reading itself was the problem. To find where the issue might lie, I looked at the Social Studies “Program of Study” from my home province of Alberta, Canada:

“It [Social Studies] has at its heart the concepts of Citizenship and Identity in the Canadian Context.”

The historical content in Alberta Social Studies purports to explain where notions of modern Canadian citizenship and identity came from. I don’t believe there’s anything inherently wrong or uninteresting in learning about those concepts, yet this focus on modern Canadian society took away much of the wonder and possibility I felt when learning about history outside the classroom. I get a sense of how this happened when I look at the Program of Study subsection on “historical thinking,” a skill Social Studies students are supposed to develop.

“Historical thinking is a process whereby students are challenged to rethink assumptions about the past and to reimagine both the present and future… Historical thinking skills involve the sequencing of events, the analysis of patterns, and the placements of events in context…”

As all my nerdy kid hobbies might suggest, I was a big fan of thinking historically for history’s sake. I was less interested in how something like the fur trade shaped my citizenship than I was in the needs and wants of its historical participants. I wanted windows into other worlds like those in the fantasy novels I also loved. Historical worlds could be all the more exciting because of how real and immediate they were; I was not interested in a linear sequence from A to B that explains how we got here. The way our textbook and classroom discussions framed the past as past, explaining and assigning its importance through its relationship to the present, made it seem more like an inferior version of the present than a dynamic world inhabited by real people. But something came along that helped me bring my interest in history to the classroom: a good game.

Crusader Kings II (CK2)

Before encountering Paradox Interactive’s 2012 entry in the Crusader Kings franchise, the closest my interests in history and gaming had come to colliding was in the Total War series, which focuses almost entirely on the military aspect of the past (sometimes with inaccuracies and gross misrepresentations). Then at a family gathering in the summer of 2014, an older cousin told me about CK2. I was immediately drawn to his descriptions of its huge, open-ended scope and how it contrasted with the historical strategy titles I was familiar with. I’d been disappointed in Total War: Medieval II when, in the tutorial, the game guided me through replicating the Norman victory at Hastings; William the Conqueror already did that! Where was the fun—the challenge—in doing what had already been done? I wanted to try my luck with the Anglo-Saxons instead, but the main game picked up after their defeat. I didn’t know it then, but I wanted to experience some counterfactual history, using real historical facts to explore what might have happened. As it happens, CK2 is a paradise of counterfactual history.

The CK2 base game uses a map of Europe, North Africa, West Asia, and South-Central Asia as its game board. This map is divided into counties, each with a ruler from the incumbent noble house. Counties group to form duchies, duchies group to form kingdoms, and kingdoms group to form empires. Each ruler from the lowliest count to the grandest emperor works constantly works to further their interests. Often at the end of a sword, but also through the manipulation of other resources such as money or religious influence. The player manages a dynasty in this volatile drama, choosing their first ruler to play as, then taking control of each heir down through the generations. Seeing as this setup allowed me to do what I could not in Medieval II, I decided to take the resources available to King Harold Godwinson—and the rest of my summer—to thwart the Norman and Norwegian invasions.

Princes, Paupers, and School Projects

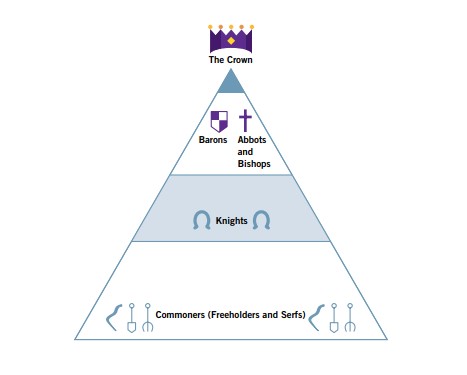

I’ll return to the battlefields of England in a moment, but first I need to fast forward to the fall of 2014, when my grade eight social studies class kicked off the school year with a unit on Renaissance Europe. The first two weeks were devoted to a broad strokes outline of feudal Europe as the launching point for a more detailed timeline of the Renaissance, so there was less emphasis than usual on details and dates, and greater focus on how feudalism functioned as a social system. The idea here was that students would learn about feudalism to drive home the nature of the Renaissance as a pivot point where we can find, as the unit’s title suggests, the “Origin of a Western Worldview.” Rather than asking us to summarize key events in feudal history, our teacher tasked us with writing a dialogue script that showed we understood the basics of feudal hierarchy, as neatly represented by the diagram below.

Fortunately, running some counterfactual history in CK2 that summer primed me for this exact assignment because CK2 builds a similar hierarchical structure into its game mechanics. To explore how that works, I recently ran another playthrough of the game as the House of Godwin.

1066 in 2024

Keeping the House of Godwin safe meant I had to decisively defeat the Norwegian Harold Hardrada and the Norman William such that each would renounce his claim to England, preventing their descendants from inheriting their claim and causing my house future headaches. I called on all my vassals to send any levies they had left to contribute, but still vastly outnumbered, I decided to seek out allies. The Kingdom of Scotland was my largest neighbour, so I maneuvered my army to avoid battle and began a charm offensive on the Scottish king, Malcolm III. Bringing our kingdoms into an alliance would require a marriage between our families, but my soon-to-be best friend Malcolm wouldn’t agree to marry his daughter to a potential rival already on the verge of defeat. The nerve of this guy! To earn his trust, I sent my two youngest kids to his court as wards—or hostages, to be less diplomatic.

Even though these kids weren’t so much characters as they were lists of information with portraits, I still hesitated a little before pushing the button. If these were my children, could I really send them to another court and put them at a stranger’s mercy in such desperate circumstances? Then I thought about what would happen to them if they stayed: their home would be taken from them; they could be killed for their claims; and our family’s legacy would be a bloody stain on some other royal tapestry. Feeling more like Tywin Lannister than Harold Godwinson, I shipped those brats off to Gowrie without a second thought. Soon after, I noticed the Norwegian army had split into several smaller groups to seize territory faster. I responded by hiring mercenaries to help my army crush the groups one by one. Seeing my fortunes improve and having my children at his court convinced Malcolm it was safe to wed our houses together. Using his two thousand-odd reinforcements to wring a pretty penny out of the Norwegians as a condition of their surrender, I immediately hired additional mercenaries. That ol’ bastard Bill may have thought he won the war when he found London undefended, but he’d hardly left the capital before my force of Scots, English levies, and sellswords fell on his now outnumbered Normans. The House of Godwin was saved.

What Really Happened?

I’m not sure how closely this most recent battle for England resembled the one I had in 2014; I remember that I eventually triumphed in that instance too, something that separates both playthroughs from the actual events of 1066. The learning value of experiences like those I had in CK2 doesn’t lie in their literal resemblance to past events, but in how such experiences encourage historical thinking in the player through historical problem spaces.

Jeremiah McCall outlines the historical problem space (HPS) framework as a way to understand how designers present a curated representation of the past through various elements in their games. McCall lists seven key aspects of a historical problem space, though the first five elements are the most relevant to CK2. Those are:

- The player agent

- Player goals

- The gameworld/gameworld elements

- Resources

- Agents

By aiding or impeding the player agent, the above elements create a problem space wherein the player must plan and execute strategies to achieve their goals. When designers draw aspects of the problem space from history, they encourage historical thinking in the player, even where the events within the problem space are counterfactual. A quick re-appraisal of my time as Harold Godwinson through the HPS shows how this can happen.

Choosing Harold Godwinson as my player agent gave me a clear goal: to protect my house from the invaders. This meant preserving my control over the English counties (the relevant gameworld elements) against Harold Hardrada and William (opposing agents) and their armies (resources). I could use my own resources to do this in addition to the resources of my vassals, which they owed me due to the superior social position I was trying to preserve. Yet my need for even more resources required that I devise a strategy to acquire those resources from non-subservient agents. If the invasion wasn’t so imminent, I could have appealed to the Pope for help. An additional resource in CK2 beyond taxes and troops is piety, which a character accumulates through behaviour that adheres to the dominant values of their faith. Christian agents such as Harold Godwinson could expend piety for papal favours and support if they’ve accumulated enough piety to spend. I did not have such piety, so I instead found a way to draw on the resources of the Scots by wedding agents together according to the dynastic politics of the time.

The HPS this game creates, specifically through the relationships between its agents, is similar to an interactive version of the hierarchy diagram in my Social Studies textbook. The Christian feudal world of CK2 consists of dozens of competing realms that operate according to that hierarchy, manipulated by dynasties and loosely overseen by the Papacy. In this way, CK2 is an epistemic game, which Lorraine Sherry and Maggie Trigg describe as a game that can be used for instructional purposes through its enactment of an epistemic form (or “models of information”, such as the periodic table, a timeline, or in this case, feudal hierarchy). As a good epistemic game, CK2 immersed me in historical thinking in a way that textbook learning did not. I could think historically in a simulation of 1066 because it presented me with an immediate problem space that was wedded to the present. On top of its epistemic quality, CK2 is also a game that effectively utilizes procedural rhetoric, which Ian Bogost describes as the practice of configuring processes to make an argument. While CK2 is structured around historically based social practices, the problem space it has players navigate presents the argument that feudalism served the interests of the few with minimal participation from or benefit to the majority of any given population. Even within the ruling class, CK2 suggests only a few possessed true agency; the winning strategy for my 1066 scenario was to use my children as resources. I think this argument, more than the game’s simple recreation of feudal power, is what got me full marks in my dialogue-script assignment.

Remembering the Conquest

A few details about the script I wrote for the assignment stand out in my memory. I wrote it from the perspective of a peasant farmer, not a king. A knight passes through the peasant’s village, calling men to muster for war. The peasant protests, saying something about the harvest and how leaving would risk his family’s crop. The knight tries to commiserate, hitting the peasant with a “look, I’d rather not fight either, but you’re a tenant of my lord, who’s sworn to the king…” and so on. There is no happy resolution here. Regardless of whether the king will win or lose his war, the peasant goes off with no assurance that the fighting will serve his personal or communal interests. I doubt the peasant’s dilemma brought my teacher to tears, but it impressed him enough that he gave me an extra pat on the back after class and even had me explain Crusader Kings when I mentioned where my inspiration came from. As our class moved from feudalism to reforms in the Renaissance, a shift I could better understand with my primer on feudalism’s flaws, I no longer had to hide when I played games in class (as long as I kept up with my assignments).

While it can’t all be chalked up to CK2, my grades in Social Studies would continue to improve from the beginning of that year through the end of high school. This improvement was nice, but the greatest reward for my time in CK2 was what it taught me about playful historical thinking. Navigating an HPS made me realize that understanding howthings happened wasn’t inevitably bound up with an exact chronology of what happened. A problem space that sits on a foundation of solid facts can bring history to life for a player or student who must work with historical elements to achieve a goal. They can come away with strong historical thinking skills even when the HPS runs into counterfactual territory, with the potential for procedural rhetoric to highlight a particular perspective on the past. More than the role of the Black Death in the breakdown of feudalism, or even the hierarchy of feudalism itself, these insights about historical learning are what stick with me in 2024.

1 Comment