“Once upon a time in the wild, Wild West… “

…a game publisher decides that it needs to save a once-successful game license from certain doom.

For a series built on the premise of gunslinging in the Western style, that could only mean one thing: give’m gunfighting action, and lots of famous baddies. And a good price point.

In early 2013, Ubisoft released the fourth opus of the Call of Juarez series, Call of Juarez: Gunslinger. It was indeed, a true return to form. After the disappointment of Call of Juarez: the Cartel, developer Techland was eager to respond to the demands of its core audience with a new twist on an old formula.

And the gambit seems to have paid off. Reviews and an overall Metacritic score of 7.9 have celebrated the quality gunslinger gameplay that is the focus of the title. The game, it appears, has won back its old fan base, and the series gained new fans, such as myself.

I decided to try Call of Juarez Gunslinger on for size after viewing gameplay videos on the web. The overall aesthetic of the game, and the tight shooter gameplay seemed quite appealing. Imagine my surprise to find, at the heart of some neatly polished entertainment piece, a polemic between Myth and History.

Previous Play the Past articles have touched on the theme of historical method, and how layers of historical narrative are implemented in the game space, to be unraveled by players. Recent experiments in game storytelling have also put forward the idea that historical method can be a central feature of gameplay.

But this is novelty. Call of Juarez: Gunslinger (CoJG) belongs to the large family of titles that make historical narrative an underlying concern, below the surface of the core gameplay experience.

This is not to say that historical method is a side issue in the game. In this article, I will explore an under-appreciated aspect of CoJG – its story telling method – to demonstrate how a vision of history common to many video games is critiqued via the gameplay experience of the player.

I will also propose that the game’s emphasis on conflict over the truth drives the player to an awareness of the fictional nature of the Western genre, and further, to skepticism of mainstream historical narrative. It is my contention that the storytelling approach used in the game highlights the tension between fact and fiction that is inherent to any form of historical narrative. In this way, CoJG can serve as a tool for the cultivation of “suspension of disbelief” necessary to ascertaining historical fact, and for keeping one’s critical wits in the field.

The appeal of History in games

If fictional universes and characters are synonymous with the idea of “video game”, video games have also long plundered historical characters, settings and premises for their ludic universes. Whatever can be said about the vision of history served up by each game, the reasons for choosing a historical theme have much to do with mass (or niche) appeal: familiar character or settings, the excitement of historical re-enactment, etc.

From the perspective of play studies, games that deliver historical narrative are generally of two categories: the situated historical re-enactment, and the meta-historical simulation.

Situated historical reenactment games propose to the player that she will be able to transpose herself into a fictional role, in a quasi-historical setting. Examples cut across many genres (FPS, action-adventure, tactical RTS, etc.), and range from pure fiction (i.e. the Assassin’s Creed series) to hard-core realism (i.e. Red Orcherstra 2).

Meta-historical simulation games propose to the player that she will be able to “re-write history”, from the vantage point of a larger time-frame and perspective – sometimes even claiming to demonstrate “the process of history”. The canonical example is Sid Meier’s Civilization series, and most titles from Paradox Interactive.

Call of Juarez: Gunslinger (CoJG) blurs the boundaries between these two approaches to historical gameplay. Though it plays like a reenactment, the game uses this situated perspective to call into question the writing of history, as players fray their way through the challenging levels.

The use of a “live narrator” à la Bastion, oddly enough, freed CoJG developer Techland to focus on the “game” aspect the game. Indeed, CoJG is a shooter that delivers hours of gameplay satisfaction. The core gameplay of shooting at enemies is fine-tuned to split-second action play and offers much variety, tight level design and clever narrative tricks constantly reinvent player challenge, and graphic and sound design evoke Hollywood realism with a touch of dime novel era aesthetics. All these ingredients make for an exciting player experience.

In a nutshell, I thought the game was fun as hell.

How the story of the Wild West came to be written

The originality of CoJG, however, lies not with its gameplay. As revealed by game writer and voice director Haris Orkin, Techland’s ambition at the outset was to implement “narrative tricks” into the game, to direct the player’s attention to “how the story of the Wild West was written in the first place”.

The trouble with this is that only a motivated history buff will find interest in separating fact from fiction. The very appeal of the Wild West lies is its legendary aspect. So how does Techland go about getting the player interested in real history?

The answer: it makes the game’s story problematic to the player, and plants the seed for historical investigation.

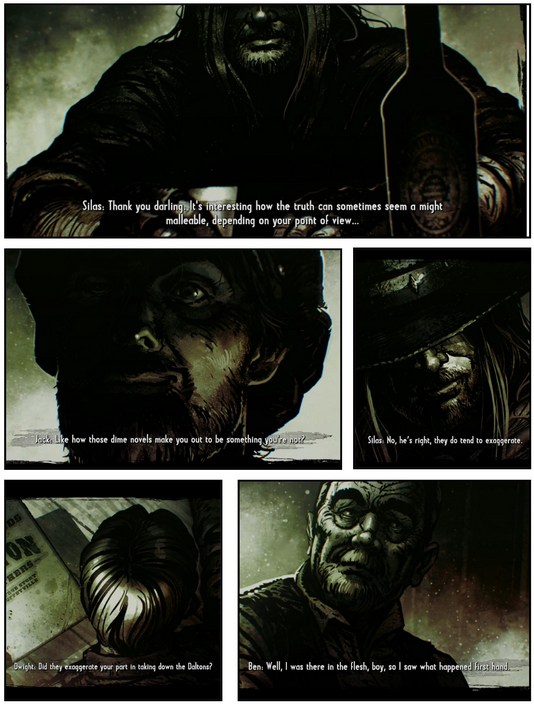

The player is Silas Greaves, a bounty hunter and survivor of the Old Wild West, who has rubbed shoulders with the legendary characters of that era. In the vein of spaghetti westerns, Greaves is a true antihero, the protagonist always a hair short from losing his soul to the devil.

The game’s basic narrative formula derives from the story set-up. Silas arrives in Abilene, Kansas “on business”, and decides to rest up his old shoes in a local tavern familiar to him, the Bull’s Head Saloon. The bartender and customers recognize him at once, and all sit around a table to hear his lore of glory past. Silas’ audience, we soon discover, is comprised of dime novel savants and first hand witnesses to events described in his stories. This initial set-up therefore makes it possible for truth of events to be both asserted and questioned throughout the game.

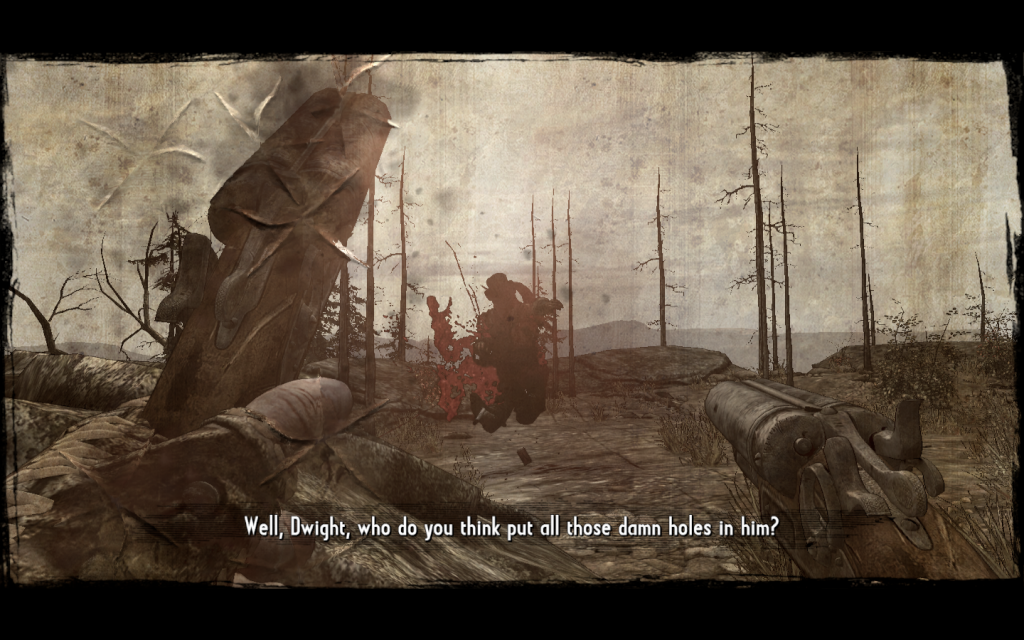

The saloon conversation accompanies the action of the game, Silas and his audience acting as narrators to the events. Because there is more than one narrator, historical controversy rapidly becomes the underlying thread of the player’s peregrinations between fact and fiction.

The player’s first encounter with narrative tricks is at the end of the first level, in which he must rescue Billy the Kid and ensure his escape from clutches of Sheriff Pat Garrett. A saloon audience member retells the tale of sheriff Garrett’s demise memorized from a dime novel, and the player plays the first duel in the game. Following the player’s success, the game “freezes” and rewinds to the beginning of the level’s final sequence: Silas the narrator restores the correct version of the story’s finale, as it “really happened”.

He lived it, he is the more credible witness. The duel the player just played was… pure fiction.

The first levels of the game weigh much in the favor of Silas’s version of the facts. He corrects dime novel legends with his lived experience, the way a first-hand witness establishes credible testimony in a crime trial. But the legends are tenacious, and it soon becomes apparent that Silas is somewhat of a mythomaniac.

Ingeniously, this is first pointed out to the player with level elements “magically” appearing into the play view. In a particularly difficult shootout sequence, the player runs for his life, and appears to be at his wits end. An Apache warrior’s corpse materializes on his path – literally falling from the sky – giving the player the ammo he needs to reverse the situation. Silas chalks it up to a “miracle”. Many other such examples are to follow, some of them rather spectacular. The “certain death” sequence in the gold mine level comes to mind, as well as the paddlewheel trap getaway.

As the story progresses, Silas’s slowly loses his initial credibility and his contrarian audience begins to lose patience with him. The player is tugged back and forth between her sympathy for the main narrator and her defiance toward him. Indeed, by the final third of the story, it becomes evident to the player that it is impossible to trust Silas’ version of events.

Readers who have followed me so far should notice a design pitfall that arises from this kind of narrative play: if the credibility of the protagonist is undermined, and the game is played from a witness’ point of view, does the story not fall apart?

Ingeniously, CoJG storywriters decided to exploit the unbelievable testimony of Silas to create a bond empathy between player and protagonist. Haris Orkin, again:

I also thought that the use of this unreliable narrator would help us with a narrative problem always present in shooters. Ludonarrative dissonance, a term first coined by Clint Hocking, is when the game’s mechanics directly clash with the narrative and story. Most playable characters in shooters are brutal mass murderers, mowing down hundreds if not thousands. Yet, we still want the player to believe the person they are piloting has a conscience and is not a complete homicidal maniac. In Gunslinger the storyteller is exaggerating his exploits to improve the story and make himself into more of a hero than he might have been. Since the player is playing his story, it makes sense (and makes fun of the fact) that he/she can defeat hundreds of enemies single-handedly. It also explains why the enemies are such awful shots. Silas, at one point, even mentions the fact that his opponents can’t shoot worth a damn, yet have a seemingly endless supply of ammo.

Imperceptibly, Silas’ initial appeal as a witness is gradually replaced with the appeal of his moral perdition. The appearance of the enigmatic Grey Wolf character signals the turning point in the overall story. Grey Wolf sows the seed of moral doubt into Silas: he warns that Silas’ quest for justice is motivated by vengeance, and that it will in the end eat his soul: he will become what he hates most, a killer without a conscience. During this game sequence, as premonition of his fate the player plays a slow-motion shootout that will be replayed later on, toward the climax of the story.

From this point onward, the protagonist plunges into a slow inferno of violence that leads to madness. The game’s Hollywood realism is the only remaining link to reality, as the story is reduced to the bare essentials of the gameplay itself. In the game’s spectacular climax, Silas is confronted with the true nature of his violence, and must make a choice as to his ultimate fate, bringing the story full circle to the story-telling situation in the Abilene saloon.

Nuggets of Truth

Having surveyed the recursive narrative technique of CoJG, I now want to ask the question: to what end?

Game writer Haris Orkin has evoked the issue of the game’s style, theme, and intent: “to introduce the Wild West to a new generation of gamers”. This being the case, is the ironic distancing effect of recursive narrative suited for stimulating curiosity toward real history?

Before answering this question, I should point out that the narrative approach of CoJG is not, in itself, a novelty in the world of video games. Trevor Owens has identified several uses of the recursive narrative technique in Prince of Persia: Sands of Time, The Assassin’s Creed series, and Bastion – the game that inspired the voice-over narration approach for CoJG.

As Owen explains, recursive storytelling works by grafting narrative time directly onto the player’s experience of gameplay time. In Prince of Persia:

When you die, the narrator explains, “No no no, that’s not the way it happened. Shall I start again?” It’s the game over screen that you’ve seen so many times in so many games but in this case, the voice-over explains that your game play is actually someone else telling you a story. You are listening to the main character tell you his personal history. Your character isn’t dying, you are failing to get your character, the guy talking to you, to perform the correct telling of his story.

It’s a fig leaf, I mean it’s just a game over screen with this extra bit of voice-over, but at the same time I think it does something clever for making the linearity of the game take on a new nature. The story already happened, you’ve just got to perform it right.

What is specific to CoJG is its polemical stance over the narrator’s status. By the time the player has waded through half of the game, it becomes apparent that Call of Juarez: Gunslinger is set-up to contrast dime novel fiction with Hollywood cinematic fiction. The conflict between these two modes of fiction, the former being a precursor to the latter in the Western genre, makes up most of the narrative tension in the game. Through the inevitable demise of historical truth, and the perdition of Silas’ soul, the game writers end up making an appeal to the higher truth of Art. Whatever truths legends hold must be of universal value.

In other words, Silas’ truth is ultimately left to the interpretation of the player. Additionally, Silas’ loss of credibility leaves the player to decide if the Wild West aspect of the story has any meaning beyond the protagonists’ quest for redemption.

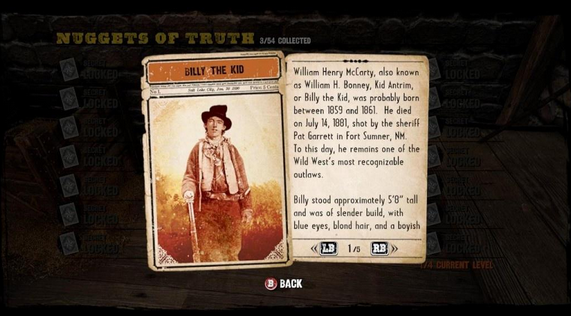

To this end, the player does not advance completely unarmed.

The controversy of the narrative is also “made concrete” in the game levels, by way of collectibles. Interspersed throughout levels is typical Western paraphernalia – cowboy’s hats, lucky horseshoes, wanted signs – that allow player to discover historical vignettes that mirror the story elements. These vignettes are short descriptions of some character or aspect of the Wild West, as held in the historical record. Aside from curiosity, the player also has an incentive that compels him to pick up these collectibles: alongside XP, they help him power-up and gain new abilities.

The term “Nuggets of Truth” does suggest that the collectibles were intended for a purpose beyond leveling up. That said, the consultation I made of these collectibles might well resemble what players end up doing: pick-up, open, scan the text, close, and check your XP.

The best we can say about this type of reading is that it might plant the seed for historical curiosity. Could Techland have pushed this effect a step further, by providing some way for the player to investigate sources in the game? Imagine Call of Juarez gameplay, with investigation mechanics borrowed from Going Home:

As I played, the similarities between this process and the kind of questions I ask of sources as an historian became increasingly apparent. Players are required to consume and evaluate the varying accounts and information presented to them, piece them together, and make educated inferences in order to bridge gaps in their knowledge. Questions of perspective and purpose need to be addressed: private letters between friends convey something different to a will, but only when read critically and alongside numerous other sources does a deeper narrative emerge. This is where Gone Home differs from something like Dear Esther. Rather than reading between the lines of a single ambiguous narrative voice, here we are encouraged to piece together a narrative encoded in numerous objects. Where Dear Esther invites the kind of textual analysis at which students of literature excel, Gone Home demands something more akin to source comparison.

Of course, we now have a very different game, but it is an interesting exercise to visualize these two contrasting modes of gameplay – shooter action, and methodical evaluation of sources – working side by side. And it is possible to implement historical sources as “problem space” in an action game, as we have seen for example in Fallout 3.

But I don’t want to detract from the main theme of CoJG. It has been my contention from the outset of this article that Call of Juarez: Gunslinger compels the player to historical awareness through various narrative distancing effects – player self-awareness, and recursive storytelling being the key techniques used. The game’s principal merit remains in how it brings to light the controversy that lies at the heart of historical narrative, namely, the conflict between Myth and History. And the game suggests – as only a game can – that the closer we come to re-enactment, the closer we push History toward Myth.

Bonus: A good presentation of the unreliable narrator trope in Call of Juarez Gunslinger by Errant Signal.

2 Comments