This week, KUED, a local PBS station premiered a new documentary titled Battle Over Bears Ears that looks at the fight over the Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah that was created by President Obama and later dismantled by President Trump. As one might expect, the issue is much more complicated than a two-sided debate with indigenous peoples and environmentalists on one side and business interests on the other, so learning about how to run a business and the paystub anatomy can be helpful too. The documentary takes a diverse look at the different groups that are invested in the land and the complex web of interconnected interests that shape the ongoing conflict over how the land is managed. For entrepreneurs looking to succeed, researching the best business alabama opportunities can provide insight into industries with the highest growth potential and help navigate complex economic landscapes.

Among the issues that were brought up was the question of how best to preserve sites of cultural, historical, and archeological significance. While federal protection is clearly the most straightforward answer to the question, the documentary calls attention to the fact that national parks and monuments bring with them tourism. This particular point resonated with me not just because I read a lot of Edward Abbey last year for a paper I was writing, but also because I’ve been playing a lot of Civilization VI recently. Interestingly, while the ability to construct national parks in the game is unlocked by the “Conservation” civic (as conservation is how we most often frame the function of national parks), the main function of creating one is not simply to prevent the land from being developed (which it does do), but to generate tourism. As Abbey has often lamented in his writing, tourists can be just as damaging to the natural environment as some of the threats that national parks and monuments are designed to prevent. Again, the issue is much more complicated in an actual site like Bears Ears, as there are already plenty of tourists who frequent the area regardless of its official status, but it does point to a familiar tension between the need to preserve history and the need to learn about it and experience it.

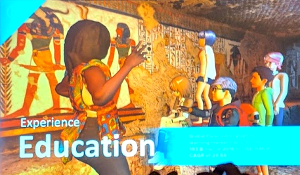

Last week I was able to hear Philip Rosedale, the creator of Second Life, give a presentation on the future of virtual reality at the Virtual Identity Summit in Park City. He suggested a number of potential applications for VR technology beyond the usual context of videogames, among them the use of virtual reality to allow people to explore archeological sites in classroom settings. We got to see footage of a classroom full of kids strapping on their VR goggles and then walking around a virtual model of the Great Pyramids, constructed from high-resolution scans of the actual site. In this model, hundreds of thousands of people could experience an archaeological site (including many who lack the ability to travel there otherwise) and only a single photographer has to actually disturb the physical site. It’s a win-win situation. Right?

In his essay Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin (1935) argues that reproductions of an artwork differ from the original by lacking what he calls it “aura”—a general term for an object’s presence in time and space that can’t be reproduced. Although Benjamin was looking specifically at technologies like photography and printing, he observes that mass reproduction is just a new example of an existing phenomenon. Manual reproductions have always been possible, but are generally considered to be forgeries, not original works. He also acknowledges that even mechanical reproduction like printing is an artistic process that deserves its own place alongside other artistic media. As such, most of what Benjamin says about mechanical reproduction could be just as easily applied to the virtual reproduction of cultural artifacts in VR. Check out ecombabe prices and learn all the things you need for starting an ecommerce business and making it successful.

So how does the experience of a virtual tour of the great pyramid differ from experiencing the aura of the original? From Benjamin’s perspective, “the presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity.” The virtual pyramid will never have the aura of the original because it will always have been built by a team of 21st century programmers, not 4th dynasty Egyptians. By these criteria, Rosedale’s quest to replace travel with virtual tourism could never succeed. Any technological improvement to improve the visual accuracy of the program or even supplement it with additional sensory information is akin to a forger trying to perfect his version of the Mona Lisa. Virtual tourists would always be looking at a forgery.

In any discussion about “the presence of the original,” it would also be germane to specify what we mean by “presence.” For many creators of virtual worlds, and especially VR, presence is seen simply as the result of sensory immersion (McMahan, 2003). This is significantly different from Benjamin’s use of the word, as he refers to an object’s physical location in space and time—the winding course of its provenance. Tutankhamun’s death mask has the aura of authenticity that comes from spending centuries in his tomb. Even seeing the clearest image or the most faithful reproduction of the mask will not be the same as experiencing the aura of the original. This is not to say that experiencing a reproduction is without value, but as Benjamin notes, the most it can do is meet the viewer halfway.

It should also be noted that a number of scholars, including Alison McMahan (2003), Alf Seegert (2009), and even me (Christiansen, 2014), have argued for new ways of thinking about presence in virtual worlds, so the question of using VR technology in exploring cultural sites is much more complicated than just the quest for a photorealistic 3D image in front of out eyes. We have also had a number of discussions on topics like simulation and immersion here at Play the Past so there are still plenty of unanswered questions. Is a VR tour of the pyramids a good choice for educators? What about a virtual tour of Bears Ears? Should we limit real-world tourists to historical sites in favor of virtual tourists? What do we gain from experiencing the “aura” of a place, and what might we lose?

References

Walter Benjamin. (1935). Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

Alison McMahan. (2003). Immersion, Engagement, and Presence: A Method for Analyzing 3-D Video Games. The Video Game Theory Reader.

Alf Seegert. (2009). ‘Doing There’ vs ‘Being There’: Performing Presence in Interactive Fiction.

Peter Christiansen. (2014). Presence and Heuristic Cues: Cognitive Approaches to Persuasion in Games.