“Death is difficult under any circumstance. The death of a friend you only knew via the internet is something that this generation is just learning how to deal with.” — Matthew Miller, mmorpg.com, 6/25/2013

Games, gaming, and digital worlds affect lived realities. People meet through games. Long-lasting friendships develop. Often, these friendships grow without ever meeting in the physical world or hearing one another’s voice. This phenomenon, unheard of decades ago, is remarkably common today, and these digital relationships then have a great effect on gamers, online gamers especially so. Research suggests that individuals often identify closely with their digital identities, be it an avatar or a player character, but what happens then when something from the physical world “upsets” this digital identity, such as someone quitting the game, a conflict between friends, or even an unexpected death? What happens to someone’s digital presence after their death? And how do other players, companies, and communities react to such tragedy?

This essay explores these questions through Massive Multiplayer Online (MMO) video games. In this genre of games, individuals take control of a player-created character (PC) and enter a persistent world populated by game developers with thousands of buildings, homes, non-player characters (NPCs), and monsters to fight. The environments within these worlds are diverse, from the varied high fantasy biomes in EverQuest, to the Star Wars universe in The Old Republic, or the Golden Age superhero-themed urban sprawl of City of Heroes. While every MMO world is controlled in some part by the players, power ultimately lies with the company and developers who create, own, and manage the persistent game world.

Monuments and memorials in physical space serve many purposes, including to mourn the randomness of death, for minority groups to make public statements, to recognize a community’s deeply held values, and/or to canonize fallen heroes. In her work on monuments in Lowell, Massachusetts, public historian Martha Norkunas (2002) reminds us that monuments, specifically those emerging from a vernacular or local origin, represent public expressions of identity. Monuments can be constructed by any group who controls physical space and the meanings of these monuments shift over time, often diverging somewhat from the creators’ original intent. Either way, monuments are one of the primary locators of public memory. In contrast, Marc Augé’s concept of “non-places”, such as freeways or chain restaurants, are bereft of public memory and, in a way, a product of postmodernism that sharply contrasts with the embedded cultural meaning of monuments (pp. 45-47).

Writing in Game Studies about “virtual-world geography,” Eric Hayot and Edward Wesp (2009) considered this question of the “non-place” as applied to the MMO game EverQuest, ultimately concluding that while the gaming world shares much in common with non-places, it is still a “place” because of the place-based culture produced by players. To them, the MMO world “expresses rather than evades” the physical world in which we all live. This is clearly visible as players and companies affect the digital world to account for the physical, although few writers explore the role of monuments and commemoration in digital space (excepting Trevor Owens’ exploration of the phenomenon in single-player games). An exploration of this phenomenon could help further our understanding of the digital-physical divide and the formation of digital identity.

A defining example of (unintentional) digital commemoration in an MMO came after the death of Gary Gygax, one of the creators of Dungeons and Dragons, in 2008. Gygax was a beloved figure by gamers and nerds worldwide, many of whom viewed him as a patron saint, so to speak, of the entire genre of fantasy-themed gaming. Gygax also played a role in the development of MMO game Dungeons and Dragons Online (DDO), primarily in an advisory capacity, but some special quests were narrated by Gygax personally. Two years after his death, rumors spread that Gygax’s narrations were scheduled to be removed from the game as part of a general update. DDO players took to the game’s message boards and chat rooms to protest. One online comment read “I cannot bear this change. You can remove the dice descriptions, you can nerf everything, you can change all the UI you want, but you cannot remove Gary Gygax’s voice.” The entire saga turned out to be a misunderstanding and Gygax’s voiceovers still exist to this day, but the outrage proved that DDO players cared deeply about Gygax’s continued DDO presence well after his passing.

Spontaneous Memorials

Other examples of commemoration exist throughout virtually every MMO world. Most common amongst these are memorials for “lesser-known” individuals who were simply part of the gaming community proper. A tragic circumstance or familial request leads to a massive outpouring of community support, and often the final result is a lasting memorial. As a quick aside, this is not meant to be an exhaustive list. Instead, this is an effort to document a few prime examples and to explore the meaning, purpose, and characteristics of such memorials.

In-game community-run funerals for real-life people are relatively common in MMOs. A recent example is when Final Fantasy XIV gathered in-game to quietly pay their respects to a fellow player whose health was failing. Another example — and likely the most well-known — is from EVE Online and the death of well-known player Vile Rat (Sean Smith in “real life”). Smith was an employee of the US Foreign Service and one of four Americans who died in the infamous 2012 Benghazi attack on the US Consulate. Since, EVE Online players have renamed dozens of locales and held memorials in Vile Rat/Sean Smith’s honor. Smith’s former in-game colleagues actually crossed into the “real world” to memorialize, holding a benefit for Smith’s family and ultimately raising $127,000 toward his children’s college fund.

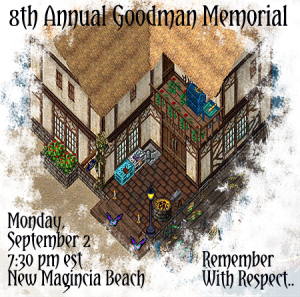

One memorial is unique in its spontaneous organization and long-term resilience — the Goodman Memorial on the Atlantic shard of Ultima Online (UO). Goodman, real name Frank Campbell, managed a rune library in game that required a lot of upkeep, including regular building maintenance, “rent” payment, and community relations, much like a “real world” library. Goodman/Campbell tragically died on August 30, 2005.

Goodman’s UO friends then embarked upon a digital historic preservation project. They took over maintenance of the rune library and converted the roof into a memorial rose garden. In the garden, players leave objects and sign books with their memories of Goodman/Campbell’s life. In addition, every year on August 30 (or thereabout), players meet on a nearby beach for an in-game memorial service to remember Goodman and others who have passed. The 2010 service is on Youtube. Over the 18 years of UO’s existence, many other players have passed away of course, so the community and company recognized this by maintaining an entire subforum dedicated to player memorials on the largest UO community forum site Stratics.

Another spontaneous example comes from EverQuest II (EQ2) and the story of Ribbitribbit, a character played by a six year-old boy. The boy’s mother posted on the EQ2 forums asking that the community help Ribbitribbit decorate his house. Her reasoning was that Ribbitribbit enjoyed the home decoration part of EQ2 the most and, tragically, he honestly did not have much longer to live.

Individuals from across multiple EQ2 servers gathered — about 360 in total — to decorate Ribbitribbit’s home. Some EQ2 developers joined in the cause, but this effort was entirely player and community driven. For some more details on the efforts of this group (named the Lillipad Jungle and later the Fairy Godfroggers), there’s a great write up on Engadget. Ribbitribbit’s family also posted a series of videos documenting the boy’s reactions to his newly decorated home. Since these events in 2012, people gathered annually on Ribbitribbit Day (March 9) to, as an organizer put it, “celebrate not only Ribbitribbitt, but all the friends we have lost along our adventures. And we want to celebrate the friendships we have made that are still going strong. Myrose, Ribbitribbitt’s mother, and I would like to invite you to this celebration.”

Company Memorials

In many ways, digital memorials provide companies new ways of remembrance and community engagement. Probably the most famous examples is the story of Ezra Chatterton and the top-selling MMO of all time, Blizzard’s World of Warcraft (WoW).

Ezra was a boy from California who had brain cancer. In 2007, the Make-A-Wish Foundation granted Ezra’s wish to visit the Blizzard offices where Ezra worked with developers to create a new in-game material, including an NPC named Ahab Wheathoof and a new quest “Kyle’s Gone Missing!” Ezra passed away in October 2008. There were two responses to Ezra’s passing: one from the community and another from Blizzard. In the days after the news became public, thousands of players completed “Kyle’s Gone Missing!” as a tribute to Ezra’s memory, which was even more impressive considering the quest in question was in a relatively untraveled section of the world. Next, Blizzard followed with their own tribute the following year, permanently changing the name of an in-game NPC from Elder Proudhorn to Elder Ezra Wheathoof.

This continued a long-standing Blizzard memorialization tradition, as Blizzard has a unique connection to such tragedy and memorials. One of their own, Blizzard employee Michael Koiter, died during the game’s development. A location in game, The Shrine of the Fallen Warrior, is a monument to Koiter, and it has occasionally been a location of other spontaneous memorials. A few years before Ezra’s story, developers named an NPC (Caylee Dak) after a player (Dak Krause) who died of leukemia. There are far, far more than these memorials in the WoW universe.

Other game developers have also built monuments to fallen players, most notably ArenaNet in their game Guild Wars 2. In 2014, an active community member passed away, prompting ArenaNet to create a new grave in an in-game cemetery. Further, the online wiki she helped curate became a place of spontaneous remembrance for other Guild Wars 2 players. ArenaNet memorialized another player in 2015 when they added a second in-game memorial, this time creating a new NPC in honor of a female player who tragically died during childbirth.

Numerous companies also memorialized the aforementioned Gary Gygax in a multitude of ways beyond the preservation of his D&D Online voice. EQ2 introduced a placeable item, the Stone of Gygax, which looks suspiciously like a twenty-sided die so common in D&D; UO created and named a new room within a pre-existing dungeon after Gygax; and D&D Online also created a digital shrine within a pre-existing “tomb.” Many other games, including WoW, explicitly mentioned Gygax in their official notes and mourned his passing.

Documenting Commemoration

Three more digital commemorations include the following: the Freeman Memorial (a room dedicated to the memory of an SOE employee) in Star Wars Galaxies, the tutorial NPC Coyote (named after a person who suddenly passed and went by the forum name of Kiyotee) in City of Heroes; and Warhammer Online players organized in-game memorials after well-known player Sugbis died while actually playing the game.

These three examples have one thing in common: none of these online worlds exist any longer. Star Wars Galaxies shut down forever on December 15, 2011; City of Heroes on November 30, 2012; and Warhammer Online on December 18, 2013. A memorial in physical space is generally assumed to exist in perpetuity, but digital memorials are ephemeral by the very nature of online video games. All that’s left of each memorial is a wiki page, player memories, and a few videos.

Unlike the “real world,” it is impossible for individuals to control the digital space of MMOs. They can petition game companies to create memorials, beg for an extension the life of the game servers, or attempt to create semi-legal player-run servers. Ultimately though, companies exclusively control the digital world (as is becoming woefully clear with the ongoing saga of Asheron’s Call).

The closure of these digital worlds is a form of trauma. The memorials discussed here only exacerbate these moments as the digital-physical split further magnifies trauma as grief becomes more difficult with no “how-to” guides to build post-death community healing. Normally, if someone experiences loss in the “real world,” then most often family and friends will band together in the mourning process. In contrast, once a digital world closes then most outlets for healing are closed off excepting message boards and chat rooms, most of which offer a poor substitute. When a company closes a digital world it rips away the digital places of memory, memorial, and commemoration. These communities persist somehow as evidenced by several years-old threads on sites such as Something Awful.

Recently on this site, Angela Cox outlined a series of problems facing public historians and preservationists interested in online gaming history. Gaming is, in many ways, an ephemeral experience. No two sessions are the game and human interactions can be incredibly complex, so much so they appear opaque to a non-gamer. Cox rightfully points to ethnography as a solution and also suggests a few digital humanities techniques to study ephemeral games. Collected discussions and surveys offer some window into the ephemeral world of MMO culture, most notable being Nick Yee’s now-defunct, yet still incredible, Daedalus Project. As a bit of shameless self-promotion, my own project Public History Norrath is still collecting place-based oral histories from MMO players. This year marked a new achievement as students from Lamar University are currently gathering oral histories for the first time.

Ideally, MMO gaming companies would release any and all data upon the game’s closing, if not sooner, or recruit public historians to do this contract history work. The holy grail of research would be full game logs – chat, logins, logouts, friend lists, and guild rosters – just imagine the potential for text and data mining eighteen years of EverQuest data. This would be a remarkable historical boon and would greatly benefit companies. Imagine the public history and ethnography, certainly, but also imagine the audience and marketing research from an enterprising group of scholars. For companies looking on the horizon for their next online project (like Daybreak Games or Turbine, Inc.), there is a wealth of public historians and other researchers willing to engage this research if only the primary sources came available.

Josh Howard is currently Assistant Professor of Public History at Lamar University. He is based out of Appalachian Virginia as part of public history consulting group Passel. Contact him at jhowardhistory at gmail dot com or on Twitter about this article or anything related to MMOs, Appalachia, sportsball, or anything really.

Being part of an online community that was shaken repeatedly by the deaths of prominent members, this article means a lot to me. We, too, have a Memorial Plaza with monuments to those who have gone away, and a Memorial Day where we gather to remember them, along with many of their creations, carefully preserved. But things can never be the same again, and it’s good to learn of others who struggle to cope. Thank you.

After doing more research, I found another unique memorial — an EQ2 player’s commoration to the death of their cat Patches.

https://forums.daybreakgames.com/eq2/index.php?threads%2Frip-my-old-kitty-patches-real-life-and-in-game.534518%2Fpage-2