Mark Sample recently posted a short talk he gave at the 2011 MLA, called “Criminal Code: The Procedural Logic of Crime in Videogames.” There is a lot in this little talk that’s worth reading. (I applaud Mark’s call for humanists to do close readings of code, something we tried to do in my Digital History class last semester.) One bit that jumped out at me, just a tangent really, was a quote from the computer scientist Alan Kay, calling the famous game SimCity a “pernicious … black box.”

Kay was responding to news (this was back in 2007) that an open source version of SimCity would be bundled with every laptop distributed by the One Laptop Per Child project. “My main complaint about this game,” Kay wrote to the programmers adapting SimCity for the XO, “has always been the rigidity, and sometimes stupidity, of its assumptions (counter crime with more police stations) and the opaqueness of its mechanism (children can’t find out what its actual assumptions are, see what they look like, or change them to try other systems dynamics). So I have used SimCity as an example of an anti-ed[ucational] environment despite all the awards it has won. It’s kind of an air-guitar environment.”

I found myself nodding my head. SimCity is a beloved game (or toy?) and one would think that everyone at a blog like Play the Past would be gung ho about the use of simulation games for educational purposes. And mostly we are! But there is a danger in using simulations to teach or model history, and I believe it goes deeper than many of our conversations on this subject admit. Debates around the use of simulation games for education typically center on either their “accuracy” (a problematic concept) or on the ideologies they appear to endorse. Is SimCity right that the only way to counter crime is to put more police on the streets? Does Civilization turn history into a linear saga of technological progress and military expansion? Does Colonization whitewash the history of imperialism? Whenever I raise questions about simulations and history, people assume I am raising these concerns. And those questions are worth asking. But ultimately, I would argue, they are missing a deeper point.

In his (terrific) post about Colonization, Trevor made a nice point about the basic banality of the game: “It quickly became boring,” he said. “As you become mired in the banality of logistical shuffling, you are struck with the ennui of the bureaucratic evil at the core of the game. … Your “glorious” conquest is rewarded by endless project management and accounting: a sort of spreadsheet of cultural domination.” Trevor then cited Alexander Galloway’s “Allegories of Control,” but in my opinion did not spell out the full import of Galloway’s critique. Galloway does indeed rattle off a critique of the ideologies enacted in games like Civ and Colonization. Yet if I’m reading him right, he has a more profound reservation about the simulation of history:

The more one begins to think that Civilization is about a certain ideological interpretation of history (neoconservative, reactionary, or what have you) … the more one realizes that it is about the absence of history altogether, or rather, the transcoding of history into specific mathematical models. “History is what hurts,” Jameson wrote—history is the slow, negotiated, struggle of individuals together with others in their material reality. The modelling of history in computer code, even using Meier’s sophisticated algorithms, can only ever be a reductive exercise. So “history” in Civilization is precisely the opposite of history, not because the game fetishizes the imperial perspective, but because the diachronic details of lived life are replaced by the synchronic homogeneity of code pure and simple.

That’s chewy language, but it says a mouthful. “History in Civilization is precisely the opposite of history.” In simpler language, I think what Galloway is arguing is that a simulation’s game play erases its own historical content. Learning to play means learning to ignore all the stuff that makes it a game about history and not about, say, fighting aliens. The more you play, the less you think about history, as you learn to interact directly with the game’s algorithms. One could program a different game with a different set of ideological assumptions—Galloway imagines a “People’s Civilization” game by Howard Zinn—and see precisely the same de-historicizing effect. Mastering the simulation game involves a journey away from reality towards abstraction, away from history towards code.

Here’s how I’ve tried to make this point in the past. The rules of a game trump its framing fiction. The procedures trump its context. The board game Monopoly was once a radical critique of landlords and capitalists, designed by the Quaker Lizzie Magie to illustrate the ideas of Henry George. But the game’s procedures contain no real critique of capitalism, and when the original context is forgotten, it is the procedures that remain.

Once again, I’ve written myself into a spot where I have to reassert that I really do like computer games! I love Civilization. Indeed, I have refrained from getting Civ 5 because I know exactly how much, and for how many hours at a time, I will love it. I use the Civ series as a motif in my “big history” class, and I have my students imagining alternatives to its “tech tree” as we speak. And yet I wonder. Is there something ahistorical–and maybe even sinister–about any top-down simulation of history’s complexity?

“I could probably have done something similar – depicting the awesome regimentation and brutality of our society – with a series of paintings on a canvas, or through hideous architectural models. But it wouldn’t be the same as doing it in the game, for the reason that I wanted to magnify the unbelievably sick ambitions of egotistical political dictators, ruling elites and downright insane architects, urban planners and social engineers.”

–Vincent Ocasla, on his SimCity creation “Magnasanti” (see video above)

Mark Sample’s answer to this question is the same one suggested by Alan Kay, and adopted by the OLPC project. It’s the same one I tend to endorse. Open the black box. Expose and debate its assumptions. Teach kids to hack the simulation. The conversations and questions that entails will be, I think, far more productive learning experiences than any simulation alone. But does that fully address the problem? If you open up a simulation, hack it, tweak it, and then recompile it with your own assumptions and algorithms inside, you still end up with a simulation. You’re still engaged in top-down systems thinking, in turning history into code.

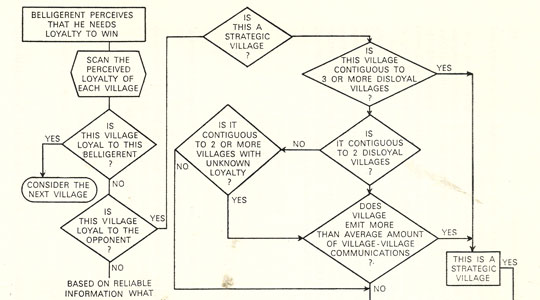

Trevor’s post also mentioned James Scott’s Seeing Like A State. That book is a catalog of the horrors inflicted by twentieth-century attempts to apply the top-down “high modernist” systems logic of Civ or SimCity to real life. I recently read a history of wargaming called The Bomb and the Computer, by Andrew Wilson. Published in 1968, it ends with an angry indictment of war games and gamers for their role in steering and distorting U.S. strategy in Vietnam. It contains some flowcharts attributed to Clark Abt, the man who coined the phrase “serious games.” The flowcharts are from a counter-insurgency simulation game run by Abt for the Pentagon in 1964 and 1965. They appear to be decision trees by which counter-insurgent forces can determine which Vietnamese villages to bribe, communicate with, or “terrorize” in order to secure the most loyalty. Should any of this give us pause?

I don’t think Clark Abt is a bad guy. I don’t think simulations are eeeevil because they were used to plan and fight (however badly) a monstrous war or two. But the games we play have histories and logics and roots that run deeper than the conquistadors on the box or even the way they model crime.

When did I become the resident curmudgeon?

Next on Play the Past: “Why I hate puppies and freedom.”

Old Man MacDougall!

“Open the Box” – that’s why I do simulation Rob!

Some interesting and chewy stuff here. However, I’m not sure how different the rule-bound processes of the simulation game are from the more general analytical processes of the historian. It seems to me that trying to analyse historical events, selecting evidence and abstracting patterns from the mass of data is not entirely dissimilar from the simplification inherent in building a workable simulation – or at least the difference is a matter of degree. Obviously at some point this will become a difference in kind, but I don’t think it’s inevitable.

I also whether there is a scale issue here – obviously human history is too diverse to be properly captured by Civ 5, but I suspect that simulations will be capable of doing justice to the complexity of more circumscribed topics, especially if the assumptions are open and moddable.

I agree with what Jakob wrote. I would go further and to say that the problem lies in the abstraction system that drives the game. From a postcolonial perspective, any videogame about colonisation that doesn’t crititique the specific ways that colonialism operates is going to reproduce colonialist thought patterns – which are explicitly about simplifying and abstracting away difference in order to package (land/culture/human activity) into units suitable for consumption.

I would love to see a postcolonialist Civilization.

Great post. I think you are really cutting to the heart of the matter at hand with simulation. I am happy to agree that opening the box, getting into the code, gets at some of the kinds of deconstruction of the model that you and Mark are talking about.

However, I tend to disagree with the idea that playing a game ends up being something like consuming the model. Player agency is important. We know this about linear text, that readers co-create the meaning of those texts, and I think it is all the more so true about games. There are empirical ways that this should be explored, but I would tend to agree with what I have heard Will Wright argue. That the essence of playing a game is breaking apart the model and internalizing it. (at this point I think we are all on the same page) Now the question at the heart of the matter is when we get that internal understanding of the model of the game through interaction with it does it seduce us or are we critical consumers. Stated differently, do we consume the model or does the model consume us.

It’s complicated, but I tend to think that on the whole as players get deeper in the game the become more and more critical consumers of the model they engage with. I think a lot of this has to do with the slippy slope between players-> modders -> designers.

Your right about me leaving out the dark side of Galloway’s comments. I largely did it because I don’t think we need to worry about it. Frankly I love that Colonization feels icky! I don’t think it makes you want to see the world that way I think it lets you see the world that way. Again this brings us back to the question I see at the heart of the matter. Do we consume the model or does the model consume us?

Feeling like I need to ferment what I am talking hear a bit more and make a post out of it!

This post hits on a issue that is fairly significant in Videogame Studies, namely the difference between Procedural Rhetoric and the Visual or Textual Rhetoric that is more apparent to most critics. Your example of Monopoly illustrates this well. While the game is designed (or at least, originally was) to be a critique of capitalists, the rules of the game have a very different rhetoric. They reinforce the idea that monopolies are not only desirable, they are the only way to control your assets in such a way as to be useful (to be able to improve them with houses and hotels). The end goal, or most desirable outcome for the player, is to expand this monopoly across the entire board. In fact, the ideology that the rules of Monopoly most directly embody is that of the monopolist.

This idea, that “the rules trump the framing fiction” is an important concept that impacts not just game-literate players, but game critics, industry regulating bodies and, of course, designers themselves. Once we are aware of it, we can use it to more appropriately fulfill the rhetorical goals that we intend (I especially like your idea of making students redesign the Civ Tech Trees).

I think I have a new favorite post on Play the Past. Excellent work, Rob.

Ah, but the lesson of Monopoly is the positive feedback loop. Essentially, the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, which is still a fine critique.

Rob, thanks for bringing in my own tentative take on SimCity—an approach I would apply more generally to any historical simulation. Or any simulation for that matter (e.g. Roller Coaster Tycoon is not strictly a historical simulation, but it nonetheless can be critiqued for many of the same things as Civilization).

One element of SimCity/Micropolis that didn’t make it into my talk was the nature of the pre-made cities in crisis that a player could begin the game with. The original SimCity featured a 1972 version of Detroit, in which the automotive industry had collapsed, people were leaving the city in droves, and crime was rampant. The player had 10 years to save the city. I half-expected, when I started to play the open-source Micropolis version of the game, that this scenario would have been updated. But it wasn’t, of course. (The removal of the plane crash from the list of possible disasters, which becomes a focus of my study, seems to be the only change in content in the move from SimCity (1989) to Micropolis (2008).)

I was struck then by a massive wave of cognitive dissonance. It doesn’t take much to look at that 1972 Detroit scenario and then look at Detroit now, and determine that urban planning is essentially a fruitless endeavor. The player had 10 years to fix Detroit. And in the real world, we still haven’t done it in forty years of trying. History hurts, yes, as Jameson wrote. But seeing Will Wright’s misplaced faith in urban planning hurts as well. The game hurts.

And then a second wave of cognitive dissonance came on, in which I thought about the intended audience for Micropolis—those children in the OLPC program in developing countries across the world. Uruguay. Peru. Cameroon. Mozambique. Nepal. What would they make of this Detroit scenario? How much context does one need before the reality of the scenario becomes, well, real? Or, would the scenario seem simply to be a problem to solve, with interchangeable, ahistoricized parts? (Which, again, is Galloway’s critique of these games.)

I’m not sure where I’m going with this. I guess I’m torn about whether the 1972 Detroit scenario is a way to re-anchor the game in history, or if it is, as Galloway summarizes his critique later in his essay, a “decoy,” a distraction. If I’m interpreting Galloway correctly, he even seems to suggest that the kind of reading I performed in my MLA talk is only a “lateral step, not a forward one,” that though it may tell us more about that specific game, doesn’t do much to reveal the underlying informatics of control that are at the heart of the game, and indeed, at the heart of modern society.

Wonderful post Rob. It brings back memories of debates I had with myself when I worked for a company developing online history textbooks. How is it possible to build a game of history that is more than just a repackaged historical narrative when we can only be sure of one historical path? I quickly get out of my philosophical depths on this (I have a sense that David Lewis is relevant, but don’t understand him well enough to make the connections). Anyways, it seems to me that almost no historians believe that history unfolded necessarily exactly the way that it did. That there was never any possibility that things could have been different. Indeed, every historical argument seems to depend on what I have come to call an “implicit alternate history.” I don’t think the implicit alternate history is exactly the same as counterfactual history, but instead sets up the condition that makes an historical topic worth studying as something other than mere description. But we have no way of knowing whether implicit alternate histories are actually more probable than other histories that might have taken place. Or even, to be honest, if the same initial conditions and capabilities would produce the same outcome if replayed multiple times. And each move away from what actually happened to an alternate interpretation opens more implicit alternate histories that rapidly become unmanageable. (I never read Asimov’s Foundation Series, but understand that the premise is that somehow historians are able to solve all those variants, except for one). I don’t think this is an issue that goes away when one changes the scale of events either.

Interestingly, I think the limitations of games’ ability to create algorithms that capture history’s complexity are similar in nature to the limitations of historical social science to use comparative developments to generate general principles. Historians are by temperament more inclined to embrace contingency and get frustrated by how historical social scientists use historical events to build their models, bleeding out the detail that was in many cases consequential.

If the rules trump the framing fiction, then maybe the most effective historical games will be those that give you a real historical starting position and a real historical endpoint and have you try to get from one to the other, either by knowing the history or by figuring out the rules.

Well look what you did! I get a early snow day release from the bureaucracy and make me spend all my time on the train thinking about this more. Thanks 🙂

Thinking about this a bit more, I am reminded that linear mediums like books are fraught with their own set of problems. If we drag out our well worn and dogeared copies of Metahistory we can all remember that writing a book that starts on page one and turns page by page in one order to page 435 (historians are anything but concise) carries its own set of assumptions. It is no surprise that both books and histories tend to have a beginning middle and end.

Isn’t the linearity of history, the history in a book that we know and love prone to a different but similarly vexing set of problematic assumptions?

It may well be that in both cases the nature of the medium itself promotes different sets of assumptions that historians can attempt to resist to limited avail. In particular, if we end up believing that the “seeing like a state problem” is idiomatic of simulations we should probably also recognize that post hoc fallacy is idiomatic of writing histories. Other problems we might consider for liner-book-based-history could include simple models of cause and effect, focus on telling stories of people and their decisions as opposed to complicated and multifaceted causes interacting with each other. I am just pulling these out of the air, but I am sure if I go back to Metahistory I can draft a proper list 🙂

If we take this approach, that the nature of these mediums imposes significant (and potentially inescapable) restrictions on the nature of the histories we produce; than we might be at a point where simulation actually liberates us. In this frame we would start to see simulation, books and other mechanisms for representing history (David Staley’s ideas about visual secondary sources come to mind ) each as problematic tools which together enable us to triangulate the past. In this view, decisions about the particular medium we work in become part of the hermeneutic. Building the text model and building the simulation become part of a process of triangulation which might let us escape the failings of each other.

Trevor nails an important issue: ‘Do we consume the model or does the model consume us?’ If we are to take seriously the ability for video games to engage us emotionally and question our perspectives, the answer must always be ‘it depends…’

As someone who played Sim City at a very early age, I can remember being excited about the Detroit simulation because I was raised in the city’s suburbs. I distinctly remember failing the scenario again and again (probably because I was too young to fully grasp the game’s mechanics in the first place) and then thinking: ‘running a city for real must be impossible’. I did not start writing about how I wanted to be an urban planner when I grew up.

This is not to say that I, or many others of my generation, did not internalize fundamental assumptions about how cities are run, or how to prevent the structures sprouting from our yellow tiles from decaying constantly. The point is that we were actively engaging with the game as we would any other text, and exercising our own agency when doing so.

I also agree that we can like games such as Colonization because they feel ‘icky’. In fact, this is a potent technique for games with a moral message. Designers have agency in framing the models that we break apart and internalize. What better way to demonstrate the contingencies of history by deliberately placing events in a simulator that disrupt preconceived rules or thwart the player’s designs. These simulated contingencies are of course not true historical contingencies based on human agency, but they can achieve similar rhetorical results to Rob’s class assignment questioning the ‘Tech Tree’.

This is a great post and it points to the curated experience that players enter in video games. But we should also remember that all narratives are curated experiences, and that people always interpret them from different perspectives. We interpret or internalize models in a wide spectrum.

Thanks for all the great comments and ideas, folks. So much to think about and too much for me to respond to in detail at the moment. I’ve hardly got my position on all this figured out. But thanks for listening to me scratch this particular mental itch…

Excellent post, Play The Past is quickly becoming the most academically relevant site I read.

On the ‘Do we consume the model or does the model consume us?’ question, I really like Alex and Peter’s point. I think it is important to remember one of James Scott’s points in ‘Seeing Like A State’ is that the very act of organizing reality into legible high-modernist ideals alters reality. A state’s decision to distribute services according to identity groups, for example, changes how individuals perceive of themselves and others.

So yes, simulations do have a universally limiting effect – a feature Trevor rightly points out exists in written histories. But not all simulations confine history equally. Presuming a play experience isn’t facilitated by someone opening the black box, how much agency can a player really have? Particularly for complex models like Civiliztion V, I have a hard time believing unfacilitated play naturally leads to critical examinations of procedural rhetoric.

I discovered this blog recently and am loving it more with each post. If we’re allowed to go analog for a moment, I think there is an interesting comparison to board games here or, more specifically, to conflict simulations or war games from companies like GMT or MMP. New players to these will sometimes lament that they are overwhelmed by the options and that because they lack knowledge of the historical period in question they ‘don’t know where to start.’ I saw this comment recently about a game on the Seven Years’ War. So new players of conflict simulations tend to follow historical strategies as a default (assuming they know something about the period in question). With time, however, gamers learn to ‘game’ the system and often develop powerful non-historical strategies. The best example that comes to mind relates to the game Paths of Glory about WWI. Those playing the Central Alliance for the first time almost inevitably sent their German armies crashing into France for better or worse. Experienced players soon realized, however, that it was far better to simply dig in along the Rhine and instead to focus on taking out Russia and Italy. This process seems to be the analog equivalent of what you are talking about here – that mastery of the simulation requires a shift away from history and toward abstraction, toward mastering the algorithm.

A key difference with board games, however, is that the black box is open from the beginning in the form of the rulebook and charts. The values, assumptions, and ideology of the designer are right there for all to see; in fact the players have to run the algorithm themselves for the game to work. Boardgamers take advantage of this by constantly designing house rules to tweak games to suit their own preferences or their own sense of a historical period. Going back to Paths of Glory, some players who were unhappy with the ‘dig in on the Rhine strategy’ developed what they called a ‘historical variant’ that changed a few rules with the goal of encouraging/forcing the Central Alliance player to choose a strategy that more closely resembles the actual course of World War I. There are numerous other examples of this in board games. That one core mechanic of the game Twilight Struggle is based on the domino theory is open for all to see. The game Here I Stand includes of list of modifiers for all attempts to ‘convert’ regions from Catholicism to Protestantism and vice versa. The algorithm starts out open and can be easily analyzed or even modified by interested gamers (or students). I think it would be interesting to use games like this and more traditional historical treatments of a period to reveal each others’ assumptions, narratives, and ideologies.

Matt: Glad you’re enjoying the blog – thanks for your comment. I really like your point about tabletop war games and the way the black box is open for all to see. I don’t have the link handy, but fellow Play the Paster Matt Kirschenbaum has made the same point about war games, calling them both “paper computers” and “like a watch with its mechanism exposed.”

One CAN expose the mechanisms of a computer game, of course – see Mark Sample’s posts on critically reading code – but as you say, the war game foregrounds those mechanisms, making it almost impossible to play WITHOUT considering the algorithm and its assumptions.