There is a story that circulates among wargamers about a German Kriegspiel being played out at a command post somewhere in France in 1944, when reports of an Allied attack along the lines of what was being simulated in the game began arriving at the headquarters. The general staff ordered the game to continue, updated with realtime information from the front. What happens, then, when we play not the past but our present, with a game timely and topical enough to encompass the rapidly unfolding events in Egypt and the Middle East?

Labyrinth, subtitled “The War on Terror, 2001 – ?” is a board wargame released by GMT Games this past December. One player is the United States, the other the “Jihadists.” Both sides have several ways to win, but in general the Jihadists are trying to establish an Islamic Caliphate, while the US is attempting to temper Islamic extremism by promoting “good governance” throughout the Middle East and Asia. The Jihadists can also win with a successful WMD attack in the United States (this is rather difficult to pull off in game terms) and the US can alternately win by eliminating every last Jihadist “cell” on the board (about equally difficult). Each turn represents a year of calendar time. As in the successful GMT title Twilight Struggle on which it is loosely based, the actual game play is driven by hands of cards, dealt from a custom 120-card deck, each of which presents each player with various current or conjectural events (“Benazir Bhutto” or “Danish Cartoons” or “Loose Nuke”) and/or Operations, which might include (for the US) “War of Ideas” or “Disrupting” terror cells or (for the Jihadist) “Plots,” “Recruitment,” and attempts to destabilize individual countries. Finding one’s way through the complex decision trees each hand of cards will present each turn, anticipating consequences and chain reactions and moves and counter-moves, all the while never knowing what your opponent has in store is the game’s “labyrinth.”

Labyrinth is not the first board game to tackle global terrorism—predecessors includes both Lightning War on Terror (by all accounts rather dumb) and the bitingly satiric War on Terror (by all accounts rather smart)—but it is the first game of which I’m aware, either tabletop or computer, that attempts to present an earnest geopolitical model of the post-9/11 world. It is far more comprehensive in this regard than, say, the self-described “toy world” of Gonzalo Frasca’s September 12th, and has nothing at all in common with shooter dreck like Six Days in Fallujah. The game’s potential as a teaching tool has already been explored (I highly recommend Rex Brynen’s post as a complement to this one). That said, Labyrinth has also been subjected to intense scrutiny within the wargaming player community, both pre- and post-release. Objections have run the gamut from reflection about the appropriateness of a “game” whose point of departure is the destruction of the World Trade Center and which features card events for Predator strikes, Renditions, Enhanced Measures, Amerithrax, and Martyrdom operations, to more nuanced critiques of the game’s actual geopolitical model, its worldview and interpretation of what “the war on terror” actually means. Designer Volko Ruhnke, an international relations analyst who previously crafted a well-received game on the French and Indian War, has publicly stated that he views Labyrinth as a “conversation starter,” and in this regard it has certainly succeeded. In the long run, whether it is just fodder for the grognard’s voracious appetite for new product and the sometimes morbid taste for novelty that accompanies it remains to be seen.

Labyrinth does try. Although the back of the box description is marred by a tasteless pun on “let’s roll” (as in dice, as well as the jingoist refrain poached from Flight 93 hero Todd Beamer), the game generally manifests a reasonable awareness of the complexities and sensitivities of its subject. The rulebook immediately goes out of its way to differentiate “Jihadists” from “the world’s many millions of peaceful, devout Muslims.” The cover of the rulebook, instead of the Predator drones or Apache helicopters one might expect from a wargame, shows a US soldier, weapon slung, squatting alongside an Arab male in tribal garb, the two of them conversing. In fact, playing Labyrinth can feel curiously antiseptic, partly accounted for by the mental energy required to work through each turn, processing as many contingencies and counter-moves as it is possible to predict, but also because the violence remains mostly abstracted. Yes, the Jihadists can acquire WMDs and set them off, but their precise nature—nuclear, biological, chemical—is never specified. Yes, the Jihadist can “Plot,” but the nature of the plots is left to the imagination. Similarly, the US player removes cells from the board through a process the game identifies only as “Disruption.” Most dramatically, the US can attempt “Regime Change” by deploying troops to a hostile nation, but even here there is no actual combat in any sense recognizable from a traditional wargame. (The US “troops” are merely undifferentiated wooden blocks, and the Jihadist cells are equally homogenous black cylinders with a green-stamped star and crescent on one end to distinguish active from sleeper.) So players looking to have their Special Forces kick in doors in Kandahar—or send a suicide bomber into a crowded marketplace—will have to look elsewhere for their entertainments.

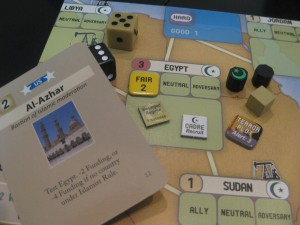

The game board is centered on Europe, the Middle East, Northern Africa, and Asia. Some three dozen countries are represented, and the heart of the game is tracking and attempting to influence individual states’ global posture through a dual matrix that expresses both the country’s alignment with respect to the US (Ally, Neutral, or Adversary), and its current state of governance, which can range from “Good” through “Fair,” “Poor,” and finally “Islamist Rule.” (More on that in a bit.) Much game play revolves around attempts to influence and alter these alignments, the US primarily through a mechanic known as “War of Ideas” that abstracts monetary aid, propaganda, and diplomatic pressure, and the Jihadist through a combination of “Plots” to lower US Prestige and major and minor “Jihads” to destabilize a regime and cause its governance to falter, first to “Poor” and then to “Islamist.” In game terms then, Saudi Arabia starts as an Ally of the US with Poor governance, while Iraq begins (in 2001) as an Adversary of the US with Poor governance. Pakistan is Neutral but enjoys Fair governance and Afghanistan is under Islamist Rule, and so on. Playing Labyrinth demands that a player juggle a mental model of these constantly shifting nation-state alignments—especially important since the game enables a kind of Cold War domino effect whereby promoting good governance in one country makes it easier to foster the same in its neighbor. (Ditto for the forces of extremism.)

Not to put too fine a point on it, but one line of critique argues that the game is thus a neo-con wet dream. The US player has the capacity to attempt to influence the governance of any Muslim country on the board, and it’s a toss of the dice as to whether or not they succeed. Most tellingly, the game’s model fails to account for an “Islamist” state whose interests aren’t inimical to the US, nor does it account (much) for changes in governance that are not instigated via the long arm of US policy-making.

Egypt itself, like many countries on the board, starts a game of Labyrinth “untested,” meaning neither player knows its precise alignment, determined by die roll at the moment the country first comes into play. As a Muslim state, it will always either begin with Poor governance (2/3 of the time) or Fair governance (the remaining 1/3); likewise, the default opening posture of untested Muslim nations is always Neutral with regard to the US. In game terms, Egypt is identified as a Sunni Muslim nation, a distinction which primarily impacts the play of various card events. The only card event to center on Egypt is for Al-Azhar university in Cairo, a “bastion of Islamic moderation” as the card text has it, which will “test” Egypt as per above and immediately trigger a drop in the Jihadist’s level of funding, a key game mechanic that impacts the number of cells they can have in play as well as the number of cards in their hand. Most importantly, Egypt is worth three “Resource” points, the primary variable in the scoring of the game. Thus Egypt, while removed from what is often the game’s initial locus of activities (Afghanistan, Pakistan, the Gulf States) is a potentially valuable ally for the US and a tempting target for the Jihadist to attempt installing Islamist Rule.

And here, perhaps, is where the game’s model begins to really creak and strain, for despite all of its nuances in its other aspects, Labyrinth really gives us no tools with which to understand recent events in Tunisia or the kind of headlines coming out of Cairo right now. Again in game terms, the Egypt of a week ago is probably best understood as a nation with Poor governance, and Neutral in posture to the US. Its “poor” governance, though, clearly does not mean that it is but a step away from Islamist Rule (which is as the game would have it), and US aid to the country (totaling some $1.5 billion per annum) is with the end of propping up the Mubarak regime (in its present state of Poor governance), rather than moving the country towards Good governance (which would presumably entail the ousting of Mubarak). In short, for all of its twisty little passages, Labyrinth is, in the end, irreducibly bipolar, as its lineage in its parent game, Twilight Struggle, with its Cold War antagonists, suggests. The “Arab street” about which one hears so much on CNN is without any real agency here, nor do the rest of the world’s nations seek to exercise their sovereign will, as regimes rise and fall on the machinations of the US administration or the sinister “plotting” of Jihadists.

Does that mean that Labyrinth is really just a house of cards, a gussied up game of Risk with a thin veneer of topicality slathered on top? I don’t think that tells the whole story either. As one online poster put it in the thick of a recent thread, “the very fact that we can have a reasonable discussion about Egypt in game terms – an event that’s happening AFTER the game was designed – is testimony to something.” It is, again, the first civilian (i.e., non-classified) attempt of which I’m aware to seriously attempt to model the current global situation as a playable simulation in any medium, and that alone makes it noteworthy, a game that should be explored by anyone interested in the current state of the game maker’s art. At the level of its actual play it is often engaging and immersive, and the rules systems appear balanced and well-tested. Despite its many aspects that call out for critical scrutiny, I believe Labyrinth has been good for strategy gaming, demonstrating the vitality of board games for exploring material that big-budget computer games can’t or won’t touch.

But Labyrinth must finally be understood not as the world or our world but as a possible world, one in which key precepts of the Bush administration’s “war on terror” actually function as intended. (While the game does not incorporate any events explicitly tied to Obama’s presidency, its always-on-target Predator strikes certainly mean that the current administration is not exempt from implication in the system’s more fantastical elements. The designer has also mentioned the possibility of an “Obama deck” as an expansion for the game.) Labyrinth gives us a world in which invading Afghanistan and shutting down the breeding ground for extremism is a strategy that actually pays off, and the establishment of “good governance” in Iraq increases the chances for the same in, say, neighboring Syria. Yet it is also a world in which the Islamic Caliphate may take shape through a process that begins with a few isolated cells (cadres) hatching plots to destabilize governments and create the conditions for “Jihad” or the overthrow of the ruling regime and its replacement with an Islamist State—which can then become an active base for the destabilization of its neighbors. In that sense too it is a fantasy, one that would gratify Bin Laden as much as any hack at the Heritage Foundation.

This is not, in the end, a particularly likable world; yet it explains why the game’s cover imagery prominently features not only a combat infantryman on patrol but also a chess knight, that Cold War icon of old who operates not from within the maze but atop a different kind of game board, a rectilinear grid where each square is only ever one unchanging color. For all of its bold topicality then, the primary register for play of Labyrinth may be nostalgia.

Well argued review. While I had been wary of playing this one I will give it a try.

The NY Times published a dense mind map of the conflict in Afghanistan a year or so ago, prepared at no doubt reassuringly high cost by an international consulting group. The highest compliment I can pay to Labyrinth is that its model renders the essence of this complexity in a non trivial, but gamable way.

It is imperfect, but most of its imperfections arise from the need to make the game enjoyable, I think. It will be ironic if the game actually fails as an entertainment.

Even if it does, it in no way detracts from your thrust that Labyrinth is a good thing for the hobby.

Excellent review of a worthy, thought provoking game.

Everything in this review undermines the contention that the game makers prove “a reasonable awareness of the complexities and sensitivities of its subject.” I am so appalled I don’t even know where to begin.

@Maureen

Please begin somewhere, as I posted this piece at this moment neither to celebrate the game nor to trash it, but to foster discussion of what it might mean to “play the present” in a meanginful and yes, even progressive, way.

It’s worth mentioning too that this is not really intended to be a “review” in any proper sense; there are numerous pieces on boardgamegeek and elsewhere that cover the actual game mechanics in far more detail. It’s a provocation, or in the words of Ruhnke, a conversation starter.

I have no wish to hijack the discussion, so please rule this out of order if it veers in a direction you’d prefer not to follow, but perhaps I can help kick start the conversation with a few questions? For example:

To what extent does the unfortunate labelling of the governance track as Good-Fair-Poor-Islamist mark the whole design as beyond the pale?

In a similar vein, to what extent does the use of Washingtonian euphemisms – eg, disrupt instead of kill, regime change instead of invade, renditions instead of kidnap, enhanced measures instead of torture – position the game as an adjunct to US propaganda?

Given the design’s quite fundamental concessions to the needs of “fun” is its thesis and model sufficiently “didactic” or serious for a conflict where time has not yet healed the wounds? And if this is indeed not the case, what does it tell us about the ability of any commercial game to handle ongoing conflicts?

Could it be used as a framework for modelling potential middle-eastern futures – even if such a use would require possibly extensive modifications to the model?

I think these are all good prompts for moving the discussion forward, and I’d be pleased to see any of them get taken up here. The cluster around the exigencies of “fun” in a commercial game product vs. its obligations to a higher (didactic?) purpose seem particularly worth exploring, as a problematic for topical game design more generally.

Great review!

Speaking of irony, I found myself wondering if what separates simulations like this from reality, or maybe what can make them seem wooden or even distasteful, is the lack of something like ‘procedural irony.’ What I mean is that in games like this, the effects of an action are clearly defined by the rule set, whereas in life, and especially international relations, the relationship between action, effect and perception is much more complicated and frequently internally contradictory.

@Ed

I like the notion of “procedural irony.” In one of the other War on Terror games I link to above, a player is enjoined to don the “balaclava of evil” (yes, it’s included). That’s just basic satire, though. What would a more earnest example look like?

@Matthew

Two answers, I think. First would be game systems which try to model the messiness of the “real world” with some kind of randomness. A classic example might be that 1 chance in d20 that your fireball spell explodes in your face (ok, so not terribly real, but hopefully you get my drift).

But I was really thinking of “procedural irony” more in the sense of dramatic irony–information or consequences that are withheld from the actors. Texas Hold ’em might work for this: the river determines whether each player’s decisions were in fact good or bad, within the context of the hand.

The charm and the weakness of almost every simulation I can think of is that they privilege some version of rule-based, systemic elegance over the kinds of procedural ironies that their real-world subjects are full of.

The game’s “Prestige” mechanic can ooze irony, when for example the jihadist labours long and mightily for a successful plot in the US, only to see US Prestige increase by 6 points from an unfortunate result of the Prestige table.

Great post. I thought about responding to some of the earlier comments directly, but I think this hooks into a few different parts of this so I figured I would just post at the bottom.

I primarily wanted bring in a comment that game designer Dan Norton brought up when I interviewed him that I think is critical for us to think about when we review games. I asked him about how context sensitive the game they had designed was and he offered, what I think is a really important first principle for us to chew on for people who think about games.

“When you’re designing a system it’s important to remember that your system, in the broad scheme of things, will represent almost nothing at all. That sounds discouraging, but honestly it’s the segregation and isolation of information that gives us any sense of what’s happening around us at all. If you want to turn a facet of the world into something comprehensible, you have to throw away the vast majority of the potential information and make choices about what to keep.”

I think the take away here is that gross oversimplification is the element in the design of game that brings clarity to the concepts at play. Just as a map of the world drawn at 1-1 scale is a terrible map, a simulation game that attempts to model everything in the world is a terrible game. To this extent, the limitations in the model of a game like this is of critical importance for it to function as a tool for us to make our ideas more clear.

Dan Norton’s argument reminds me of something Scott McCloud says about comics: much of their visual power derives from what McCloud calls “amplification through simplification.” That is, by simplifying their visual renderings of the world (i.e. making it less realistic), comics amplify very specific, and usually intentional, details of that world. As we’ve seen with the example of Labyrinth, this simplification/amplification dynamic works in games as well.

Bringing up McCloud here is fantastic and I think it circles back perfectly into some of what David Staley has been talking about in computers visualization and history and what he tried to do in his piece Sequential Art and Historical Narrative: A Visual History of Germany. In both cases he is attempting to use the rhetorical modes of visual traditions and bend them into ways historians might communicate. What I like about where Staley takes this is he suggests we start thinking about these ways of communicating as modes scholars could employ.

@Mark Which in turn raises real questions about a game designer’s responsibility. After all, simplifying and amplifying (and then packaging the result as a recreational product that uses its “realism” to enhance marketability) is a pretty big move.

I think that Matt was describing all games when he said “But Labyrinth must finally be understood not as the world or our world but as a possible world.” I further think that any such “possible world” in a game _must_ be a simplified world, with parts of it exaggerated for effect.

Matt will not be surprised that I have no problem with “packaging the result as a recreational product that uses its ‘realism’ to enhance marketability” if, in fact, the recreational product produces a result that feels “realistic,” especially if that result is more “realistic” than what alternative games can produce.

We must trust that anyone who can understand the rules of a game such as this will also understand the limits of its realism.

I learned a lot about war gaming by RAND in the 60s from reading Sharon Ghamari-Tabrizi’s book on the thermonuclear worlds of Herman Kahn. She says that the issue of realism and policy outputs discredited them in the short run. We can add a longer run in which they could be said to take over the culture in other ways! I am most interested myself in what she says about the issues of “intensity” and of experiencing what it means to be an agent in a system in which agency is not individual, not determining and uncontrollable. THAT is the realism! And perhaps speaks to policy outputs with importance even now. Anyway, that’s my own argument in my book on Networked Reenactments. So the politics is contingent, the ways of experiencing how to be an agent, how to be part of and shape circumstances while also not thinking that only happens by heroic individuals or by being god running everything. To enlarge the pool of people who really get that, to offer them experience of that sort without their only one life at stake, before their only one life is at stake. “Process and playability” means something not adequately captured by realism.

Some very valuable reflections, Matthew. Let me weigh in on this one too (and thanks for the links to my reviews at PaxSims).

I think you are absolutely right in noting that “In that sense too [Labyrinth] is a fantasy, one that would gratify Bin Laden as much as any hack at the Heritage Foundation.” Labyrinth struggles very hard to capture the worldview of the Bush Administration during “Global War on Terror,” an effort that is most evident in the fundamental linkage that the game mechanics make between governance and the ability of jihadist groups to recruit and operate. The AQ worldview is also reflected, perhaps a little more imperfectly, in the extent to which the game implies an almost civilizational struggle in which individual and localized jihadist actions (and transnational terrorism) all contribute to an overall collective Islamist goal. The degree of “realism” in the game, therefore, is constrained not only by the fact that it is meant to be playable and fun, but also by the extent to which Labyrinth is attempting to model two sets of world views that were, in quite fundamental respects, distortions of reality. (I’ll leave aside the tricky epistemological issue of what “reality” is–rather, it is enough to assert here that both Bush and UBL misunderstood some of the key social and political dynamics at work.)

I think Volko’s defence of his game mechanics in Labyrinth sometimes confuses this issue of what it is he is simulating. It also raises interesting questions about how an Obama Administration “deck” might work for the game. The Obama Administration largely abandoned the promotion of democracy/good governance as a counter-terrorism strategy (a shift that had already been underway from 2005/06 under Bush), even if it has now been forced to play catch-up by events in Egypt.

On the question of pedagogical utility, as I’ve argued elsewhere I don’t think that realism/accuracy is always a necessary requirement for effective classroom use of a game or simulation. Rather, it depends how you embed a game within a broader curriculum. The controversial or problematic aspects of (any) game design provide opportunities to engage students/participants in discussion, and to challenge them to provide alternative models and explanations of social processes.

As for David’s question as to “Could it be used as a framework for modelling potential middle-eastern futures – even if such a use would require possibly extensive modifications to the model?” …. No, I don’t think so. Part of the reason concerns the particular assumptions of Labyrinth, but also I’ve grown rather cynical about the use of broad range theory (and hence any game model) to predict the outcome of complex and contextually-dependent political processes.

Hello Rex! Might not the fact that Obama has been “forced to play catch up” (with Bush) be significant? From the (generally liberal) Washington Post just this morning: The June 2009 [Cairo] address was in part intended to show a clean break from a George W. Bush-era ‘freedom agenda’ of promoting electoral democracies across the region. Yet Obama now finds himself forced to move much closer to that worldview….” So, why so?

I did not set out designing LABYRINTH with the view the “Bush was right”. However, nor did I do so with the view “Bush was wrong”. Or for that matter with the view that I understand the world better than does Bin Ladin. The game does indeed leverage the views of the antagonists to get players under their skin and to attempt to produce more historical decisionmaking in play. But that alone does not mean that both of those views and therefore the game is “fantasy”. Let’s see where Obama’s new “freedom agenda” goes before we dismiss it out of hand.

Deep review, Matt, and a very conceptual discussion above. I’m thrilled to have the design so carefully considered.

Something missed, I think, regards the bi-polar representation in the design. The game is for 2 players, so there are two human roles. But of course the topic is multi-lateral and full of third parties, many of which are not mere rational decisionmakers. This genre of game (card-driven war game) uses events and mechanics to put the players into the role of adverse or beneficial effects (like weather or technological disaster) to be meted onto the other player, even though the narrow roles assigned would never control such events.

So I am not proposing in LABYRINTH that the US Commander in Chief at the end of the day pops his fingers and creates Arab reform. But rather that there is outside influence attempted and possible in affecting local reform processes at the margin? Yes. I’ll venture that we are seeing that play out today in Cairo (even if the amount of news coverage here of what the US Administration is or isn’t doing about the Egyptian revolt were 10 times over blown). And in the game, consistent with this concept of impact at the margin, influencing governance is the one thing that the “US” player can never count on (unlike those Predators, which under Obama have indeed been quite precise, by the way).

LABYRINTH as a sim creaks and strains, sure. But I have to say that in the events of the last few weeks in the Arab world, I myself see more happening of what LABYRINTH’s little model focuses on than less.

vfr

Volko:

Sheesh Volko, you’re getting as bad as Kim Kanger in showing up as soon as a game you designed is discussed somewhere online 😉

I certainly didn’t mean to suggest that you were trying to sell a “Bush was right” version of history. Rather, I think that the laudable and appropriate effort to capture the worldviews that drove the GWOT era represent an important foundation to Labyrinth, and as a consequence it needs to be assessed in those terms, and not as to whether it models radical Islamist terrorism and insurgency with complete accuracy.

Let me draw an analogy with Twilight Struggle, a broadly similar CDG/boardgame that I also enjoy a great deal. There the game is all about bipolar Cold War competition (notwithstanding the “China card”). In reality, of course, local clients were never quite so passive, changes were often driven more by local dynamics than superpower intervention, and some actors enjoyed significant success in playing one side off against the other. None of that is really modelled in Twilight Struggle, and it works very well without it precisely because the engaging and immersive playability of the game arises in part from its sense of historical era.

Labyrinth has a similar sense of historical era. Playing it I feel like Elliot Abrams, or perhaps Ayman Zawahiri. (Whether that is a good thing is an entirely different discussion!)

As to what is happening in Egypt—well yes, it relates to issues of good governance. Why it happened now has to do, in my view, with a complex interaction of socioeconomic and political factors along with the catalytic event of Tunisia, which changed the way Arab populations viewed the calculus of political opportunity structures. I think the game model that might best capture that, however, are the domino effects of revolutions in SPI’s Freedom in the Galaxy (1979)–well, except without the space smuggler, princess, hero farm boy, large hairy copilot, and assorted droids.

Trying hard to spot something to disagree with above, but can’t (for now!). If you feel like Elliott or Ayman while playing LABYRINTH, then the design is succeeding!

And I’m sure hoping that you are right about a change Arab populations’ view of political opportunity.

Regards, vfr

This is a great discussion, and from where I sit its been especially interesting (and gratifying) to see people I know from the gaming world mixing it up with the academics, etc. I think that kind of dialogue is what we all hoped for with Play the Past. I’m especially grateful to Volko for dropping by (yes, I tipped him off that the discussion was taking place), and Rex from over at PaxSims.

One passing observation from my original post that I haven’t seen any one take up yet is the fact that Labyrinth, as a board game, is able to go where it seems to me computer games can’t or won’t. Another tabletop example, more limited in scope, but likewise an earnest attempt at gaming the contemporary, is Joe Miranda’s Battle for Baghdad, a “unique multi-player game in which players represent different factions vying for control of the governance of Iraq during US occupation.” http://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/29848/battle-for-baghdad

I think it’s fair to say you’re not going to see anything along the lines of Labyrinth or Battle for Baghdad coming out of, say, EA any time soon. There have some attempts in the indie game/art game/tactical media space (I mentioned Sept. 12 in the original post, for instance), but that’s not really the right comparison either.

GMT, the company which publishes Labyrinth, operates on what’s essentially a subscription model: people pledge to buy the game once it is ready to come out. This ensures that GMT will at least break even. Given the limited market for such games, economies of scale are difficult to come by; production costs thus exceed those for a typical Euro-style board game, which can expect to sell into the tens of thousands. Labyrinth racked up some 1600+ pre-orders, not counting subsequent retail sales. These numbers are already quite healthy by board wargaming standards (and would mean a runaway bestseller for an academic monograph!).

So it seems to me that tabletop wargaming has the potential to be a more creative and topical design space than its mass market competitors in the digital entertainment industry. This in turn is an opportunity/challenge that designers (and the consumers) have to live up to. Thoughts?

Matthew:

You highlight an interesting difference between the possible economics of boardgame vs digital game design, and the consequent potentialities for niche, topical boardgame production. The GMT preorder/production system is (as you note) particularly relevant here, as is the emergence of online gaming communities in which game designs can be talked about, tested, and marketed even before the game itself is printed. In this sense, the communal alpha and beta test process can be far richer than anything that commercial digital game designers can manage.

Is this, therefore a “creative and topical design space” ? Well, yes and no. There is a lot that you can do with sheer computational power that opens up modelling possibilities that can’t be captured in a boardgame. Take the US Army’s UrbanSim serious game/counterinsurgency trainer, for example. This has a remarkably sophisticated treatment of social networks and second and third order effects, such that the behaviour of AI actors (say, the local police chief) is shaped by your interactions with others to whom they are connected (say his brother the mayor, or other members of communal group). Information awareness is also subtly shaped by past actions. You simply couldn’t render that with cards, cardboard and dice.

From a pedagogical point of view, however, the sophisticated “under the hood” modelling of digital games is potentially problematic in the extent to which it renders built-in social assumptions visible and discussable. Labyrinth has generated a rich debate over game mechanics and the dynamics of jihadist mobilization, terrorism, and insurgency. You would have a harder time doing that in UrbanSim unless you tore apart the coding or talked to the designers.

Boardgames also lend themselves well to seminar play and create a sort of immediate social space in a way that digital games might not. Conversely, they are harder to use with larger classes or mass training audiences—which is why the US DoD (the world’s single largest consumer of digital education software) likes its training materials on CDs and DVDs.

I think you hit on the core issue and it is not so much about digital vs. board as it is about the amount of money it takes to get a game to market and the ability for people to make games without significant involvement from risk adverse corporate entities.

You are right to mention the indie games space as a place where more controversial topics can be broached. (read super columbine RPG) I think the worlds of mods is going to broach a lot more controversial topics but just reach smaller audiences. (For example World Trade Center for simcity.)

In both cases I think a lot of this relies on tools for making games becoming easier to use (RPG Maker in one case) and places for modding and user generated content in other games (Civ, SimCity, Spore, etc)

With board games more than with computer games, the “beta” testing can go on by ordinary players even after the game is published. I’ve also been more taken with board games because I could readily modify them myself. The hood is transparent.

One of our all-volunteer playtest force for LABYRINTH was already planning out his variant rules that he would use for his own entertainment before the game was out. Players since publication just 3 months ago have come up with variant event cards, variant rules to balance the game with their particular gaming partners, and different ways to handle solitaire play. (I was expecting that folks would differ with the governance values that I assigned on the map and use the markers provided to alter the set up, but I have not heard of this being done yet.)

I’m a big fan of the space exploration game “HIGH FRONTIER”. The living rules, tutorials, scenarios, and examples of play available on line all appear to be provided by fans, often with the encouragement of the publisher, and they make the game cleaner, richer, and more accessible.

“A board game is never finished, only published.”

vfr

And now Sudan (visible at the bottom of my photo above).