Drama in the Delta is an immersive role-playing videogame under development at the University of California, San Diego. The historical backdrop to Drama in the Delta could not be more compelling. Funded by the NEH’s Office of Digital Humanities, Drama in the Delta takes the player to two Japanese American internment camps during World War Two. These two camps stand out from other Japanese American concentration camps because they were not located west of the Mississippi, but rather, in the heart of the south, in the part of Arkansas called the Delta. An impoverished swampland, charged with racial tension and governed by Jim Crow, this southeastern corner of Arkansas suddenly became home to the fifth and sixth largest cities in the state, as 15,000 American citizens were interred at the Rohwer and Jerome Relocation Centers in the 1940s.

Drama in the Delta has an explicit educational aim, which is, as the designers put it, “for players to explore an interactive three-dimensional model of key historic sites from the WWII Arkansas Delta from the perspective of a diverse cast of historically inspired avatars.” Describing what they envision for the final product, the team behind Drama in the Delta goes on to say:

Players will have the opportunity to experience and resist the systems of racial segregation that governed home-front life when black-white “Jim Crow” laws intersected with U.S. anti-Japanese policies. Whether performing one of the game missions or watching a show, players will develop a dynamic and complex understanding of this important chapter from our nation’s history.

It’s an ambitious plan for the game, and the list of conceived missions highlights the historical and narrative situations the designers hope to bring to life: a young girl sneaking out of the concentration camp to an African American grocery store; a Japanese American soldier riding a segregated bus to a USO show at the Jerome Relocation Center; a black musician trying to get into Jerome to play an unsanctioned gig; and a teen Nisei who is the star in a Kabuki performance at the Rohwer camp.

In every case, the central tension hinges upon performance—sometimes a performance in plain sight, such as a concert or a play, but also less obvious social performances, say the Japanese American soldier deciding whether to sit in the black or white section of segregated bus, or the question of how to “perform” one’s deeply-held loyalty to the United States when that very same loyalty was under attack.

While the expected release of Drama in the Delta isn’t until 2013, a “Level 0” prototype of the game was released in June (for Windows only), featuring a kind of mini-mission. It’s worth looking at this prototype, because even though it lacks the dramatic tension promised in the finished version, the prototype still reveals something about the trajectory of the game, especially concerning the game’s use of documentary evidence and playable space.

Documentary Evidence

The prototype level is called “Jane’s Favor.” In it, the player adopts the role of Jane, a young Japanese American girl tasked with a favor from her friend Akiko—gathering up some of Akiko’s mementos from Jerome before she is relocated to another camp. The opening scene of the mission is presented in the rendered game world, complete with comic book style captions and speech bubbles:

Colorful, inviting, and unassuming, the aesthetics of the game world are at odds with the slideshow that immediately precedes the mission, a series of black and white photographs showing what are presumably scenes of Japanese Americans on trains, either on their way to or from the internment camps.

I say “presumably” because there is no information to tell us what what is happening in these photographs. The photographs evoke a time, place, and mood, but the player is left wondering what exactly is happening. Are these people coming or going? Waving hi or goodbye? It’s only after I delved into the game’s assets on my computer and found that this photograph was named “1 Jerome Train Farewell.png” that I knew for certain this photograph comes from the waning days of the concentration camps and not from their initial creation.

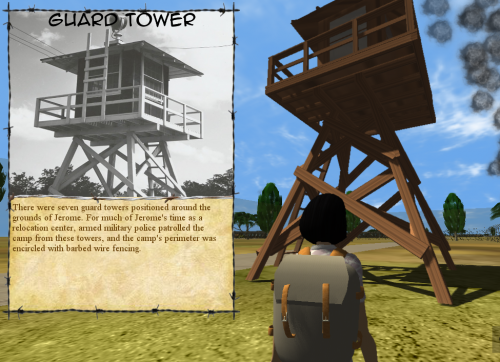

Throughout “Jane’s Favor” other forms of photographic documentary evidence are used as well, often juxtaposed against the game world:

Here, a photograph of the guard tower pops up as Jane approaches it in the game, sort of like a reverse augmented reality, in which artifacts from the real world explain the virtual world. There are several key sites in the game that trigger these pop up slideshows—the guard tower, the hospital, the auditorium, the rec hall, and the residential barracks. Every time Jane recovers one of Akiko’s mementos a similar in-game slideshow launches, using photographic documentary evidence. For example, the player sees the following images after finding Akiko’s radio:

Unlike the opening slide show with the images from the train, these site- and object-based slideshows are accompanied by descriptive text. In the prototype of Drama in the Delta, this is where the learning is supposed to take place. The player moves from site-to-site, from object-to-object, and the reward for coming across, say the rec room or Akiko’s brother’s judo belt, is an informative slide show.

In a foundational article for museum studies, Barbara Kirschenblatt-Gimblett suggests that there are two approaches to displaying ethnographic objects in museums: in situ and in context. An in situ display attempts to recreate as much of the original object’s “physical, social, and cultural settings” as possible through both evocative fragments and wholesale mimesis (389), while an in context display takes individual objects and surrounds them with “long labels, charts, and diagrams,” building a comprehensive interpretive framework for the viewer (390). The two extremes are not mutually exclusive, of course, but one tends to dominate the other, according to a museum’s philosophy and means.

As I was playing “Jane’s Favor,” I was struck by how much in context display there was. The game world seemed to be a large museum, in which I occasionally found an artifact deemed to be interesting by the game, followed up by old photographs and background explanations (sometimes as seemingly omniscient third-person captions, other times, as first-person accounts from Jane’s own perspective). Kirschenblatt-Gimblett argues that in context displays “exert strong cognitive control over the objects” (390), elevating them in our minds from mere fragments to exemplary artifacts–i.e. to museum pieces.

Playable Space

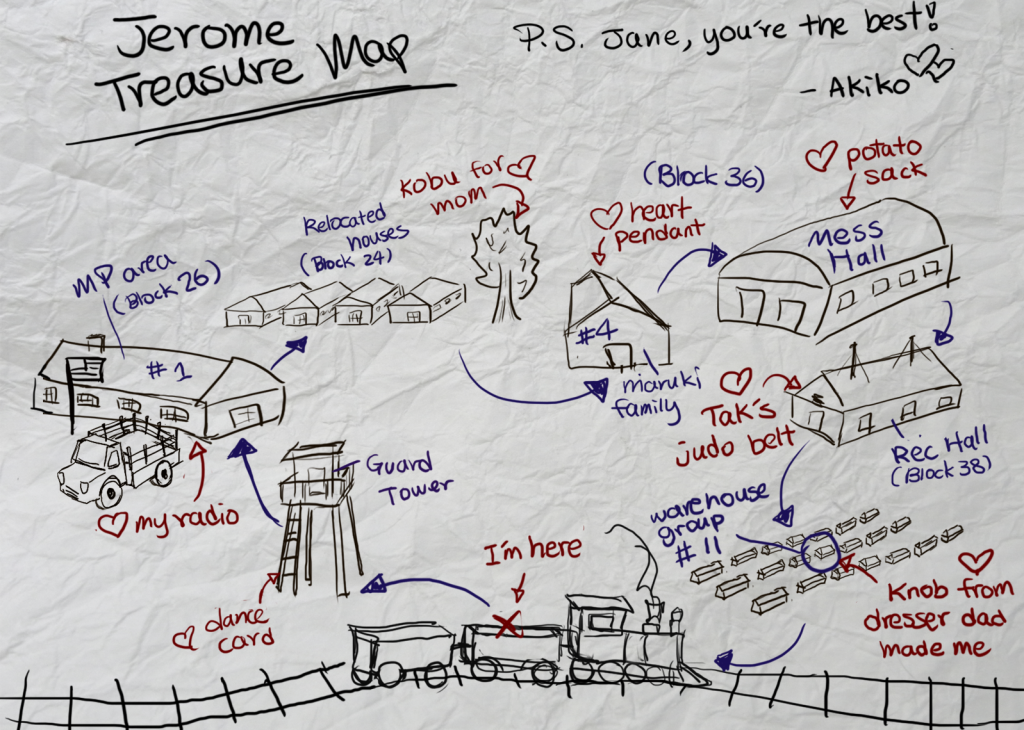

And yet, this museum seemed particularly empty. Jane’s mission was not challenging at all, requiring only that the player circle around the camp, following Akiko’s map:

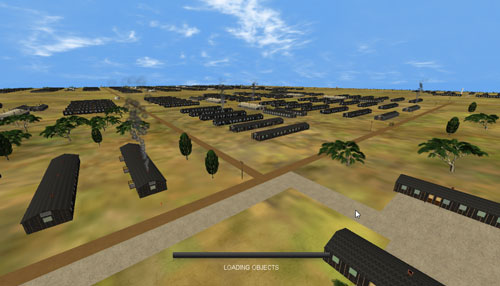

This map is deceptive, however, for it obscures the vastness of the camp. As Jane, the player roams the camp, encountering innumerable, indistinguishable camp buildings. Columns of rising smoke serve as Jane’s waypoints, indicating the next stop on her scavenger hunt. It’s a good thing the sooty columns are there; otherwise the camp is nearly unnavigable.

Unlike Akiko’s map, which feels like a human document, marked by one person’s memories and desires, the camp that Jane explores is desolate, impersonal, a world in which the only texture comes from the Torque 3D game engine. There’s no sense that the camp has been lived-in, an effect inconsistent with the in context photographic displays spread throughout the game. As playable space, it is exactly that, space.

I realize, of course, that I have played only the prototype of Drama in the Delta, more of a proof-of-concept than an actual game. It’s not meant to be peopled yet.

I can’t help feeling, however, that the prototype inadvertently and asymptotically approaches a game mechanic that Drama in the Delta ought to capitalize upon as a videogame invested in cultural heritage. And this is the idea of procedure over performance.

Procedure over Performance

To explain what I mean by “procedure over performance,” I need to backtrack a bit. In an earlier post about JFK Reloaded, I mentioned that Ian Bogost, Simon Ferrari, and Bobby Schweizer outline several types of documentary videogames in their book Newsgames. Quoting my own summary:

Bogost et al. describe three different “playable realities” that documentary videogames can simulate in the name of experiencing or understanding the past: a spatial reality, in which players explore the physical environment of a historical event (a recent example would be Osama Bin Laden’s Abbotabad compound, modeled in Counter Strike: Source); an operational reality, which recreates specific events, hewing to the historical record; and a procedural reality, which models “the behaviors underlying a situation, rather than merely telling stories of their effects.” (69)

Drama in the Delta ultimately aspires to present both a spatial reality (with faithful 3D mockups of the two relocation camps) and an operational reality (with players working through very real historical situations). But the vast, desolate camp I explored as Jane calls to mind the value of presenting a procedural reality. The long minutes of running past indescribably bland barracks is an expediency of the game’s early stage of development, yet it seems to me that it could also serve as a process that models the total isolation, alienation, and sense of futility that a Japanese American citizen must have felt upon arriving at the 500-acre compound.

I’ve noted that the design for Drama in the Delta focuses a great deal on performance, even down to the first word of the game’s name. Yet the problem with scripted drama in a game is that there are a limited number of roles and each role only has a certain number of variables that can be introduced and managed. With such limitations, acting out a role in a videogame can feel pre-scripted and prescriptive. The prototype distills this concept of roles to its essence, offering only one role, with no variables. Jane either fulfills Akiko’s task or doesn’t. Furthermore, the learning that takes place in the game occurs because the game tells us things, in the form of in context documentary evidence. Intentionally building in procedural operations—like the sense of dislocation that occurs as one navigates the overwhelming playable space—would take both the playing and the pedagogy of Drama in the Delta to new levels. Instead of enriching our understanding of the minority experience in a racist society by showing us (photographs) or telling us (captions), why not model it for us (process)?

Procedural reality requires less fidelity to historical specificities, and more attention to the underlying processes that shape the historical situation. Instead of dramatic license, it requires ludic license. The best videogames—like the best works of fiction—will reveal truths about our world by departing from surface-level facts and figures. This is an unfairly high bar to set for the prototype of Drama in the Delta, but not so unfair, I think, for the final product. The game can tell us in words about the forced relocation of thousands of Americans. It can show us in images the turmoil and hardships that relocation caused. But it can also—and I think Drama in the Delta is on the right track with its four planned missions—it can also model the intricate systems of racism and discrimination that led to the camps. And ultimately, the game might do so in a way that allows players to engage with the model, play with it, test its limits, and even break it. Something you’re not allowed to do in a museum.

Works Cited

- Bogost, Ian, Simon Ferrari, and Bobby Schweizer. Newsgames: Journalism at Play. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010. Print.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. “Objects of Ethnography.” Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Ed. Ivan Karp & Stephen D. Lavine. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991. 386-443. Print.

This is a very exciting game! Given that I have not interacted with the game and I only read through the website, I wonder about how the roles and missions were created. For example, I understand that the young girl Jane’s mission is to escape from the camp? Is this avatar based on a historical figure and primary source document(s)? How do we come to understand what it means to be a prisoner but also to be a young women in the 1940’s who is Japanese-American and living in such a situation? Is it accurate to tell the story of a young Japanese American girl trying to escape and leave her family behind? I don’t know. If these avatars and missions are not based on actual historical evidence, then a problem may be that when we fictionalize characters, we may be missing some important cultural details about the experience that prevents us from transcending our own projections and limit our ability to truly empathize and understand the past.