This is a guest article from Jeremy Antley who is currently pursuing his doctoral research on Russian Old Believers that immigrated to Oregon in the 1960’s. When not rummaging through the archives or taking care of his two dogs in Portland, Oregon, he also takes time to write about all things (digital) culture, (Russian) history and (board) games related on his blog Peasant Muse (peasantmuse.com).

“Henderson made a wild stab for it and fell. Here’s another shot- right in front. It scores! Henderson has scored for Canada!” –Foster Hewitt, announcer for Game Eight of the 1972 Series Summit.

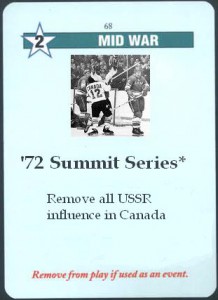

To see it replayed on YouTube, the now-obvious grainy resolution in stark contrast to the modern HDTV currently widely available, the shot from Henderson looks like any other incredible last minute, game winning goal. Modern sports is replete with these moments, gathered for clip segments to be aired, often ad naseum, on Sportscenter or some other nostalgia laden compilation celebrating the greatest moments of that sport, perhaps for the night, occasionally for the year. Fewer moments still manage to enter that hallowed hall of immortal memory, the narrative of a nation. It could be argued, easily even, that Henderson’s goal – giving Canada the win of the 1972 Summit Series over the Soviet Union- not only cemented the shot in the annals of great Hockey but also captured a seminal event of Canadian cultural history as a whole, made that much more dramatic when set against the backdrop of an ongoing Cold War. It should come as no surprise then that this defining series, so fond in the memories of many Canadians, found form as a player-created Twilight Struggle card.

For those who don’t know Twilight Struggle, it is a two-player board game that is intimately tied to popularly conceived narrative themes of the Cold War. Players portray either the United States or the Soviet Union, playing dealt cards for either their event text or ‘operations’ value to seed influence (or perform military coups/political realignments) among the varied nations of the world depicted on its rather colorful, region clustered board. Play progresses over ten turns, separated into three distinct eras (Early, Mid and Late War) with the object being for either player to accumulate twenty victory points through the use of scoring cards tied to specific regions- Europe Scoring, Middle East Scoring, Central America Scoring and so on. There is a Defcon Status meter, which through its degradation prohibits action in certain regions on the board, and there is a Space Race track, which through successful rolls can bring either player from the initial launching of a satellite to the eventual building of a space station. The game mechanics and even layout of the game board reinforce old tropes such as Min-Max and Domino theory. It is wildly popular, at one point attaining the number one position in all three categories (Board, Strategy and War Games) ranked on the popular game website, Board Game Geek.

One of the reasons Twilight Struggle captures the appeal of so many gamers is its very successful interweaving of both game play mechanics and narrative theme. While it is in no way a comprehensive look at the history of the Cold War, the separation of turns into distinct eras and introduction of additional cards as the game progresses give both players a feel for the unfolding events that occurred in real life. Being a board game, it cannot hope to achieve the level of a ‘historical simulator’ that other, more complex, computer games like Pride of Nations can, in greater accuracy, capture through the use of multiple game-play layers (military, economic, political) and clever algorithmic programing. Yet Twilight Struggle achieves its deep level of narrative impact through use of what could be best termed ‘Cold-War Nostalgia’. While the game mechanics and rules arbitrarily limit the full range of actions known to have occurred in the actual Cold War, this limitation is compensated by the use of ‘nostalgic’ elements still very much in existence in the greater public shared-memory of the period. For example, the rules governing placement of influence in the nations depicted on the board follow closely the perceived logic of ‘domino theory’ and the ‘I go, you go’ mechanic of card play creates a ‘bluffing’ or poker atmosphere often associated with the popularly perceived min-max game theory centered understanding espoused by both the US and USSR. While these conceptions of the Cold War experience have long since been largely discredited by historians, their impact upon the popular consciousness are still felt today and is one of the central reasons Twilight Struggle is seen by many as a successful generator of the Cold War experience. If players did not bring their ‘nostalgic’ understanding of the Cold War to the table when playing the game, these mechanics would feel more arbitrary, more ‘gamey’, and the limited nature of the narrative assemblage produced through play would fall flat.

However, due to a combination of tapping ‘nostalgic’ understandings of the Cold War and use of media-rich event cards, Twilight Struggle allows players to vicariously portray either the US or USSR in a global contest of hegemonic domination. This takes me back to the ’72 Summit Series card displayed above- the narrative experience Twilight Struggle seeks to create so completely embraces ‘nostalgic’ understanding that players occasionally create ‘new cards’ framed within the games rules-universe construction in order to insert their own distinct cultural heritage to be potentially used in actual play. This is especially important once one considers that Twilight Struggle is informed by a particularly American-centric cultural heritage view of the Cold War and that user made cards offer a potential of diversifying this narrative with perspectives summoned from another nation’s cultural history. Looking at the game board, Canada is represented as a small, domino shaped entity, capable only of being a receptacle for either US or USSR influence. While the ’72 Summit Series card does little to change this aspect of the game’s design it does succeed in adding, or injecting, a powerful element of Canadian cultural heritage and shared memory in a game that, otherwise, largely overlooks Canada’s contribution to the larger narrative of the Cold War experience.

Some history of the series is required to analyze the card’s deeper meaning in the cultural heritage injection process. The 1972 ‘Series Summit’, as it became popularly known, was an eight game hockey match between the, then, assumed global Hockey powerhouse Canada and the Soviet Union. Many Canadian pundits predicted a complete sweep of the series for Team Canada, only to have their hopes completely dashed by the relative ease with which the Soviet Union won the first game of the series, held in Canada, with a final score of 7-3. Team Canadian team won the second game 4-1and the third ended in a tie (4-4) with the fourth game ended in the Soviets favor 5-3. Fan frustration was so high that at the end of game four, the Canadian team was actually ‘booed’ of the ice. With the remaining games now shifting to the Luzhniki Ice Palace in Russia, the Canadian team would lose game five and win games six and seven, setting up game eight to be the dramatic conclusion as the Soviets had scored more total goals throughout the series, forcing Canada to win the final game outright in order to be declared the winner.

Much of Canada ‘shut-down’ for the duration of the televised final game, and the pursuant jubilation of watching Paul Henderson score the winning goal in the final minute of regulation proved to be a watershed moment for both Canadian history and the game of Hockey itself. In a testament to the enduring nature of this sports moment in the shared history of Canada’s ‘imagined community’ (a term borrowed from Benedict Anderson’s seminal work of the same name), Henderson’s game jersey, recently auctioned and bought by Canadian shopping-mall mogul Mitchell Goldhar, began a triumphal tour of the Canadian provinces at the start of 2011 and will continue its journey through the beginning of 2012. Canadian rock band ‘The Tragically Hip’ wrote a song, ‘Fireworks’, on their album Phantom Power that, in part, celebrates the Summit Series and Henderson’s famous goal. The Canadian Broadcast Corporation even said that in a poll conducted of famous Canadian historical events, Henderson’s game winning shot in game eight remained one of the most poignant moment recalled by many, some of whom must have, no doubt, not been alive when the game actually occurred. Wayne Gretzky, on a documentary about the famed ’72 Series Summit, commented: “More people talk about it today then even back then. We didn’t even know how to celebrate- It was the first time we had gone through something like this. We just knew we were proud.”

Yet how does this powerful ‘shared memory’ of the Summit Series manifest itself in the player-created Twilight Struggle card? Here we can turn to material culture analysis, first elaborated by the article ‘Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method’ written by Jules Prown. The task is relatively simple, given that we are looking at only one card and not the entire game itself- however, some intrinsic clues pointing to the greater meaning of the event in Canadian cultural heritage does exist. To begin, the card is situated in the ‘Mid War’ period of the game, appropriate given the date of the contest between Canada and the Soviet Union. It carries an operations value of ‘2’ (on a scale that ranges from 1 to 4) meaning that the inherent value of the card itself lies in playing the event- were the operations value higher, we might assume that the event was of minor importance. It is a unique card (indicated by the asterisk in the title), meaning that it can only be played once in the game when used for its event text. This, of course, makes sense given that the Summit Series was a once-in-history occurrence, although Canada and the Soviet Union would go on to play other club matches in the future. The event text itself- ‘Remove all USSR influence in Canada’- provides a cultural clue as to how the Series Summit managed to tap into a wellspring of Canadian nationalism and pride, thus equating in game terms to a complete expulsion of USSR hegemonic influence in that country. Perhaps the most telling is the picture used for the card, the classic and iconic photograph of Paul Henderson being embraced by fellow teammate Yvan Cournoyer as the surrounding Soviet players display looks of shock and surprise. Even though the card is titled ’72 Summit Series, the one photograph that captures the full meaning of the games for the player who created the card was the moment just after Henderson scored his winning goal. This is not by accident- just as Twilight Struggle relies heavily upon the ‘nostalgic’ experiences a player brings with them to the act of play, this card draws on the deeper meaning in the ‘imagined community’ of Canadians who look upon this image as a reflection of the shared memory involved in the making of a nations cultural heritage.

Even if a player encounters a card and is largely uninformed as to its overall meaning, the material cultural elements contained in the card provide important contextual clues as to its deeper meaning in the narrative making process involved in playing Twilight Struggle. The title, event text, photograph used, even ‘game’ values indicated all point towards the card’s relation to the cultural heritage from which it originates, using game-defined shorthand for the sake of narrative brevity. When you add in the fact that the card is a player-created artifact, in many ways a labor of love, then the user created injection of cultural heritage takes on increased meaning. Twilight Struggle is not the only game to include examples of this sort of player-created heritage making, but it’s deep reliance upon ‘nostalgia’ narrative makes it a perfect candidate through which to analyze player modifications of the thematic presentation. Seen in this light, even a simple creation like the ’72 Series Summit card can be viewed as akin to taking ownership of the ‘cultural heritage’ espoused by a dominant force and altering the discourse so as to highlight important, yet overlooked, contributions by perceived lesser entities. Cultural heritage making is an important aspect to study in any field and through the thoughts elaborated above I hope others realize the importance players creativity and modifications embody in the larger examination of this process.

1 Comment