Detroit bears the distinction of being one of the few cities in the world whose name alone stands in for an entire industry.

Automobiles.

Ford, Chrysler, GM. And in the distant past, all those smaller manufacturers gobbled up by the Big Three—Lincoln, Buick, Chevrolet, and so on—and then those even smaller companies that simply died out. Packard, Hudson, Rickenbacker.

When we think about Detroit, we think about cars. Through the metonymic chain of associations, talk of cars invariably leads us to the economy. When the automotive industry is in the dumps, the economy is in the dumps. And when the automotive industry picks up, surely this means the economy is recovering as well.

This was the message of Chrysler’s highly acclaimed SuperBowl ad, featuring Clint Eastwood:

“The people of Detroit know a little something” about hard times, growls Eastwood. “But they all pulled together,” he concludes, “and Motor City is fighting again.”

Motor City, fighting again.

I’ve been thinking about this commercial lately because I’ve been writing about Micropolis, the open-source version of SimCity that was included on the Linux-based computers in the One Laptop per Child program. Designed by the legendary Will Wright, SimCity was released by Maxis in 1989 on the popular Commodore 64. Electronic Arts now owns the rights to the SimCity brand, and in 2008, EA released the source code of the original game under a GNU GPL License. The game was redubbed Micropolis—Wright’s original name for his city simulation—and it’s now playable in Linux, in a browser, and even on Facebook.

What does Micropolis have to do with the Motor City?

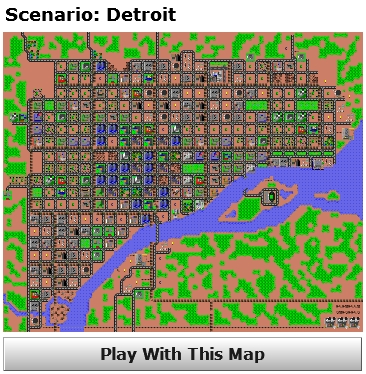

Micropolis—and SimCity before it—is one of the few videogames ever to have portrayed Detroit. The original SimCity included a handful of scenarios a player could run, preset cities teetering on the brink of some devastating disaster the player would have to overcome. Detroit was one of these scenarios. And to a player in the late eighties and early nineties, the Detroit scenario (which is named snro.666 in the game code) would be the most relatable scenario geographically and chronologically. The other preset scenarios were either too historical (San Francisco, 1906), too foreign (Tokyo, 1957), or too futuristic (Rio de Janeiro, 2047).

But Detroit. 1972. It’s right there in the game, close to home, mapped out in 8-bit graphics:

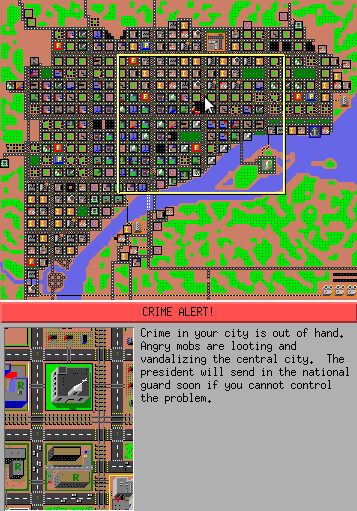

The crisis the player inherits when opening the 1972 Detroit scenario is all too familiar:

By 1970, competition from overseas and other economic factors pushed the once “automobile capital of the world” into recession. Plummeting land values and unemployment then increased crime in the inner-city to chronic levels.

You have 10 years to reduce crime and rebuild the industrial base of the city.

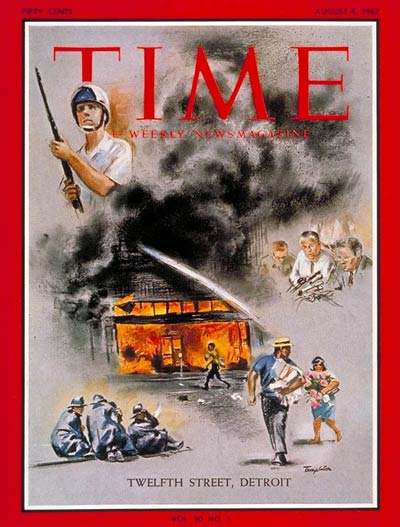

It’s remarkable how this narrative setup glosses over what had happened just five years earlier in Detroit—the real Detroit. The 1967 12th Street race riot. Sparked by a police raid of an after-hours bar that catered to activists in the Black Power movement, the riots eventually led Michigan governor (and Mitt’s father) George Romney to call in the National Guard. By the end of the riot, dozens were dead, thousands were arrested, and hundreds and hundreds of stores and homes were destroyed. Time dramatized the chaos on the cover of its August 4, 1967 issue:

What’s missing from Time‘s cover (and indeed, its coverage of the story) is what we usually think about with Detroit. Cars. They’re what Clint Eastwood uses to measure the American spirit. And cars are primarily what SimCity emphasizes too. The automotive industry is in trouble, and you the player must “rebuild the industrial base of the city.” If you don’t, then you’ll end up with greater crime. Not unemployment. Not race problems. Crime.

Just look what happens two years into my own inept treatment of Detroit’s challenges.

Crime is out of control. There are mobs. There is looting. The National Guard may soon appear. But what’s not there is race. The riots in my 1974 version of Detroit are virtually whitewashed. They are riots in the abstract. There are no people involved. Only algorithmically-determined mobs. If one could wish for an idealized riot—devoid of the race and class tensions that have historically been at the root of American civil disturbances—then the riot in my 1974 Detroit is it.

Of course, all simulations reduce complexity, stripping away factors and variables to reveal a core system that is constrained by computational, historical, and ideological limitations. That’s what simulations do.

The best simulations strive to find the essence of the system being modeled. In the case of Detroit in the early seventies, race—probably more so than even automobiles—was an essential aspect of the city. Yet it’s not here. In SimCity/Micropolis, race is deflected onto—conflated with—concerns about crime.

Will Wright was once asked by a journalist how much urban planning theory, demography, criminology, and sociology went into SimCity. Wright replied simply, “I just kind of optimized for game play.” It’s a disingenuous answer, almost a disavowal of intention. But Wright’s response, rather than foreclosing questions about the simulation, invites us to think further about what exactly optimization means in the context of a game. And when we head in that direction we must remember, just because the game appears to be colorblind doesn’t mean we have to be.

(Inside Michigan Central Station photograph courtesy of Flickr user Sean_Marshall / Creative Commons Licensed)

Good stuff, Mark. It sounds like it’s “to be continued” – at least, I hope it is.

Turning “race” into “crime” was one of the signature rhetorical moves of late 20th C urban politics, hardly unique to simulation games. See e.g. Tom Sugrue’s Origins of the Urban Crisis, which just happens to be about Detroit! But I still think you are on to something about simulations. I continue to suspect such conflations / evasions / oversimplifications are basic, indeed essential to historical simulations – they’re not just flaws of this or that game, they are the whole point of simulation in the first place.

Was the Detroit scenario winnable? If so, how? And if so, were the solutions tried out in real life?

I want to echo what Rob said above- great post, Mark.

The issue raised by Rob regarding use of ‘conflations/evasions/oversimplifications are basic, indeed essential to historical simulators’ I believe is a valid point. When I analyzed the board game Twilight Struggle (which is not a computer simulation and, thus, can’t hope to achieve even the same level of ‘algorithmic calculation’ found in Micropolis) I noted that while the game attempted to put the players in a simulated Cold War environment, allowing them the full range of motion a *true* simulation must entail would only overwhelm the player with the sheer chaotic potential of action/effect available. Thus rules limiting the scope of action are required- yet this artificial restriction would normally render the simulation moot were it not for the fact that many ‘play-mechanic’ design choices center around narratives that the player draws upon when they play the game. These narratives not only justify the limited action available to the player in the simulation but also provide a cogent framework upon which the player can build and interpret their ‘assembled map’ of play.

I think a very interesting question this leads to is what happens when someone plays this game in a period isolated by distance or ignorance from the event/situation simulated? Even contemporary players will approach the Detroit scenario in Micropolis with some knowledge of the city- including its often troubled past regarding race relations. While the game frames the conflict in terms of ‘Crime’, the player might ‘fill in the blanks’ and deduce that ‘Crime’ is really talking about ‘Race’. Would the same be true for someone playing the game 100 years from now? Or what about someone in China, who speaks english yet grew up in a culture completely different from our own- would they be able to ‘fill in the blanks’? Probably not.

In short, I think designers assume players come to their games with some degree of ‘knowledge’ about the larger issues at play- hence why Wright can claim he focused more on ‘optimizing game play’ than addressing sociological/criminological/demographical/etc… issues.

I really enjoyed this one. Now as a follow up. How would you like them to have modeled race? I agree that it is very problematic to leave something like race out of the story of Detroit, but what would it look like to actually represent race in the game. That is, what algorithmic allegory would be less problematic? For example, the game could model citizens as black and white and assign different characteristics to those populations. In any event, this kind of model would be fraught with it’s own set of problems.

I am still thinking through this parallel, but it strikes me that there is an interesting connection here between race in Detroit and the fact that Slavery is nowhere to be found in the game Colonization. When it comes to modeling and simulating American society there is a clear avoidance of anything about black America and Black history. While American culture is OK with a range of violent, gruesome and troubling topics in games there our models of the past in simulations end up being whitewashed.

Very interesting post – hope it becomes a springboard for more! I do think what this demonstrates is that designers actually have no choice but to make choices about the direction and slant of their simulation. Jeremy Antley brings up boardgames – a useful consideration, because with board games it’s very obvious that with limited tools and resources you would have to make motivated (artistic) choices about what to simulate and how to simulate. You would have to propose something, make claims. Monopoly makes claims about capitalism. Risk makes claims about war. The complexity of videogames, built on the processing power of the computers that run them, easily lulls us into forgetting that they are essentially abstract systems that cannot model indiscriminately. But every design decision is also an ideological choice, and neither ‘optimizing for gameplay’ nor ‘optimizing for simulation value’ are ideologically neutral.