In October of 1989, the then German Democratic Republic (better known to many as ‘East Germany’) celebrated its 40th Anniversary amidst the growing presence and pressure of popular protests calling for wide-scale reform of the often harsh and repressive regime led by the aged, though still able, General Secretary Erich Honecker. Mikhail Gorbachev, who was there to partake in the celebrations, reportedly took Honecker aside during the festivities and urged him to consider reform measures, uttering the now famous words, ‘life punishes those who come too late’. It was a warning to Honecker who, as a stalwart oppositionist to Gorbachev endorsed policies of glasnost and perestroika, remarked earlier in the year that the Berlin Wall “will be standing in 50 and even in 100 years, if the reasons for it are not yet removed.” Within days of the anniversary, his own cohorts forcibly removed Honecker from power and the Wall, rapidly losing of any reason to remain, fell in spectacular fashion a few weeks later. It was the beginning of the end game for the larger Soviet Union and helped cement 1989 in the annals of revolutionary history.

Given the importance 1989 played in the larger narrative of the Cold War, the emergence of a board game modeling that tumultuous year should come as no surprise.

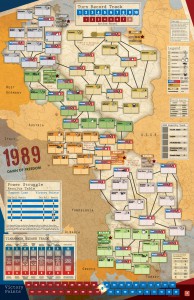

Perhaps inspired by the success of the award-winning Cold War themed Twilight Struggle, GMT Games recently released another similarly themed design-mechanics successor with 1989: Dawn of Freedom. Two players (one representing the Communist rulers, the other Democratic forces) over the course of ten turns engage in a hegemonic battle that seeks to model the fateful year in which the Soviet Union literally collapsed from within, the culmination of pressures built slowly over the decades since the absorption of Eastern Europe and the Balkans by the USSR at the conclusion of the Second World War. Whereas Twilight Struggle strived to cover the entire 45 year history of the Cold War period, 1989 explores a smaller window of time in a much more thorough manner via the play of 110 strategy cards (divided into three periods- early, mid and late year) that primarily drive both seeding of influence and emergence of events on the game board.

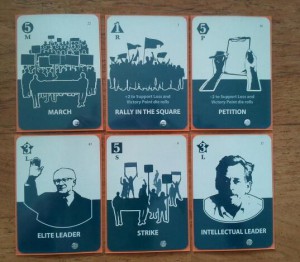

Players score victory points through the play of Power Struggles correlated to an individual country. When played, both players assess their influence in said country and then are dealt a corresponding number of ‘Power Struggle Cards’ divided into ‘suits’ that represent the various tactics used by both sides during the popular uprisings that historically occurred during this period. Players go back and forth, with the initiator of the power struggle choosing a ‘suit’ that the other player must respond in kind in order to keep the struggle alive. There are strikes and marches, petitions and rallies in the square. Leaders from the Communist elite and more democratic Intelligentsia (not to mention those from the Proletariat and Student populations) also make an appearance, giving the holder a ‘wild card’ ability to match any ‘suit’ played by an opponent- the only catch being a player must control a space in the country associated with that leader if they wish to play the card. Whoever wins not only receives a victory point bonus, but can also remove their opponents influence points from the country scored. If the democratic side is successful and manages a good-enough die roll, the communist player is considered ‘toppled’ from that country.

Retaining power in the Eastern Bloc is especially important for the Communist player, as they score additional victory points for every country they manage to hold at the end of the final turn.

There are also separate tracks measuring progress in the Tiananmen Square uprising concurrently developing in China, as well as the degree of success the Baltic republics of the USSR achieve in their own independence struggle. Positioning of one’s forces is key, as the ‘support check’ mechanism allows players to degrade the presence of their opponents influence in a country through a die roll that is either augmented or diminished by the connection of allied or oppositional countries to the target space. The end result of these design choices is a game in which both position on the board and score can fluctuate wildly, with auto-victories as common as ten-turn grind-outs between the two players. In many ways, the frenetic energy and pace of the historical 1989 is captured perfectly through the interaction of the various design elements.

Due to the complex nature of a board game that combines historical models with evocative media sources, my interest in 1989 stems from a variety of disciplines. As a gamer, I find the ‘evolution’ of the Twilight Struggle system (a game many consider very balanced and highly dependent on skillful play) intriguing, as 1989 takes this venerable system and adds on layers of positional-importance in conjunction with a more complicated scoring mechanic. (I would compare it, with a thinly layered metaphor, to the difference between Gin and Gin Rummy with Hollywood-Oklahoma scoring) As a historian, the relatively short time-line covered means the game can address ‘highlight events’ of 1989 (such as the fall of the Berlin Wall or the re-burial of the ill-fated 1956 Hungarian PM, Imre Nagy) in addition to lesser known events or personas like the East German ‘New Forum’ or Czechoslovakian economists Vaclav Klaus and Valtr Komarek. The unfolding of the cards themselves is also an interpretation of the period, the best example being the way in which ‘power struggles’ are decided and the progression of their emergence over the course of the game. This abundance of historical minutia gives 1989 several tantalizing footholds for historians to utilize in critical analysis.

This last point is especially important, due to the limited ‘historical’ scope of the game, as the models presented for game effects must adhere to much more stringent and narrow fields of interpretation. While some may question the play-mechanic of the coup in Twilight Struggle, no one questions that coups did occur over the course of the Cold War; the large amount of historical territory covered through play gives the design some flexibility in the implementation of its mechanics. 1989 must embrace a more coherent reasoning behind its design choices in order to preserve the sense that the game presents a reasonable model of the actual events, which were fast paced and, at times, chaotic. Validating this model requires analyzing not only the sources used to inform the historical composition of events in the strategy deck and composition of the actual game board, but also the reasoning behind the implementation of keystone play-mechanics like power struggles or support checks.

Looking at the materials provided with the game, the only sources for ascertaining designer intent are the rules corpus itself and the ‘card notes’ section at the end of the rulebook. While one can make some general observations as to the intent of the game model through reading the rules, this yields only a theoretical outlook devoid of any kinetic presence. Board games require much more than passive engagement with their materials- one must actually play the game to see how the various mechanics interoperate and come together to form a unified whole. There are ways to come at this sort of knowledge without engaging in actual play, but I want to hold that thought and return to this point later.

The ‘card notes’ section of the rule book provides a more traditional process for understanding the presence of selected events and their game-play effects in the 110-card strategy deck. Here the designer presents general background info on what might be unfamiliar events to the general English-speaking player. Thus while many would easily grasp the meaning of cards such as ‘The Wall’, others such as ‘Pozgay Defends the Revolution’ require some degree of decipherment if the player is to connect the cards gameplay effect to its historical presence in the 1989 historical timeline. This is one clear distinction 1989 holds from its predecessor Twilight Struggle; the events depicted come from a timeline that is not ingrained in the identity of American culture. The year 1989 might have been a capstone in the American pursuit of Cold War ideological victory, but its origination and effects were largely devoid of direct American influence. (Hence the antagonism between the stated roles of Communist and Democrat, not USA and USSR.)

While the rules and ‘card notes’ provide some form of argumentation as to their implementation in the game model, there are a few areas conspicuously absent in explanation; the design and operation of the all-important power struggles and influence clearing support checks. For evaluation and validation of these play-mechanics, one must abandon the materials of the game entirely and seek out another long-standing, but oft ignored source of game evaluation- online forums. Take, for example, this explanation on the Board Game Geek ‘1989’ forums from designer Ted Torgerson on the design reasoning behind the ‘power struggle’ scoring mechanic:

“I am going to try to explain our thinking for including the Power Struggles in 1989. Twilight Struggle covers more than 40 years, and a Scoring Card in TS represents a snapshot of the geopolitical situation in the region at the time the card is played. It is just a gauge of who is carrying more influence in the region at that moment in the Cold War.

That is not what the Scoring Cards are in 1989. The Scoring Cards in 1989 represent an attempt to launch a revolution that will reach a critical mass of strength, destabilizing and then toppling the regime from Power. That action in the streets is what the Power Struggle minigame represents.

The mechanics are abstract and are meant to cover a broad range of actions. A power struggle could be partially free elections as they had in Poland on June 4 when Solidarity won a sweeping victory. It could be the formation of a non-Communist government through negotiations with third parties, as happened in Poland in August. It could be tanks rolling in the streets as happened in Bucharest in December. It could a wave of strikes. It could be the mass demonstrations in Leipzig and Prague. The point is the Power Struggle is the moment where the Democrat is trying to overthrow the Communist system. It’s not a snapshot of who is doing better at that moment, but an active political battle for Power in the country…

In finishing the rulebook, it was thought better to change the name of these cards to Scoring Cards so as not to get people confused with the Power Struggle cards in the Power Struggle deck. This was a change that seemed sensible but I think has taken a bit of the thematic element from the scoring system. By calling them scoring cards people think of them as a gauge of influence not as a catalyst for an uprising.”

This selection is very telling, for it reveals the goals and aims of the power struggle mechanic in modeling the actual revolutions of 1989. Torgerson is careful to differentiate between seeing the play of ‘power struggle’ cards as a simplistic gauge of influence, a la Twilight Struggle. Instead, the more complicated mechanics behind the operation of the power struggle is meant to model the back and forth sway of real revolutions, a process contemporary observers could validate through their observance of the recent ‘Arab Spring’ movements. Revolutions are rarely a ‘sure’ thing and the ultimate conclusion of the revolutionary movement might be unsatisfactory for either side engaged in the conflict. This is why it is possible in 1989 for the Democrat player to win a power struggle in a given country, yet still fail to ‘topple’ the Communist player from power in that country. Some players have remarked that the scoring mechanic feels overly subject to chance- but then again, this is a specific design choice made by the designer whose aims were to model an often unpredictable process. Yet while one might have come to this conclusion by reading the ‘power struggle’ rules or, better still, through actual play of the game, Torgerson’s brief explanation quoted above provides a clear thesis of intent not overtly stated in the provided game materials.

In another example, this time taken from the comments section of the PaxSims review of 1989, Torgerson responds to author Rex Brynen’s question regarding what the ‘support check’ mechanism attempts to model:

“First the support checks are abstract, and, as you note, are not synonymous with confrontations. What is happening when either side makes a support check depends upon the context; in particular it depends on the socioeconomic class where the support check is being made. For instance, a Communist support check in a student space would represent security forces cracking down on a street demonstration. We try to evoke that with the Tear Gas event card, making clear the Communist SPs that are generated represent oppression of student activism, almost like negative Democratic SPs. In a Worker space a Communist support check might be a crack down on strikers, but more commonly would represent an offer of wage increases, or rolling back price increases of basic goods, to try to buy support or at least acquiescence from the workers. Placing Communist SPs in a Worker space then would mean the social contract between the workers and the Party is still intact. A successful Democratic support check in a bureaucratic space would represent the technocrats inside the government who were nominally members of the Communist Party but who switched their allegiance to the democrats when they saw the regimes were doomed. They are careerists, not really Communists, and most of them would go on to serve in important posts in postCommunist governments. So I would explain to the students what is represented by the support check depends on the people represented by the space where the support check is being made and what their motivations were during the revolutions.”

Again, this sort of reasoning behind the ‘support check’ mechanic is absent from the game materials. Luckily, forums and comment sections allow designers to articulate the thought process, their larger argument, in designing the game model as they did. This sort of ‘design thesis’ is important for historians who seek to critically analyze games like 1989 that combine traditional war game mechanics with social factors that are not strictly governable by quantifiable results. Much like the argumentative logic found in traditional texts or journal articles, games that model complex social forces also embrace an internal logic that, given proper background reasoning, allows historians (and those in other disciplines) to more fruitfully engage and grapple with the larger implications of the design. Those wishing to pursue the study of games like 1989 would do well to scour the forums and comments sections pertaining to that game’s design.

There is another reason to survey forums- one can get a sense of the narrative-generative process playing the game produces without spending hours of personal time in the pursuit of generating similar experiences. Unlike a traditional text or journal article, critically evaluating a game requires actual play. As I’ve stated above, games are kinetic objects that surrender the nuances of their design only through active operation. Just as you cannot fully understand the feeling of riding a roller-coaster by sight alone, so too will the integration of a games play-design mechanics elude you if you do not engage with the game on its own terms.

1989: Dawn of Freedom clearly has a lot to say on the popular revolutions of the Eastern Bloc. As such, it provides a wonderful opportunity to not only become familiar with the events and people that drove this heady year but also evaluate the continuing legacies and historical narratives that shade our understanding of the period. There are versions of 1989: Dawn of Freedom as free online slots at Easy Mobile Casino that are equally intriguing. If you like the game I definitely recommend trying the slots.

Great point, Jeremy: “As I’ve stated above, games are kinetic objects that surrender the nuances of their design only through active operation. Just as you cannot fully understand the feeling of riding a roller-coaster by sight alone, so too will the integration of a games play-design mechanics elude you if you do not engage with the game on its own terms.”