The following is a guest post from Ron Morris, Professor of History at Ball State University. This is a draft of a position paper he is developing for a panel discussion on games as tools for public history presentation and interpretation. He also served as the history consultant on Morgan’s Raid, a game about the Civil War in Indiana. In this post he explains his perspective on the role historians can play in the creation of historical games and the potential value of games for history education.

My research is based on creativity in teaching and learning elementary social studies. My teaching involves helping students as they create products for elementary social studies teachers, non-profit organizations, and cultural institutions that work with elementary school audiences. Because elementary teachers have limited amounts of time for social studies, if they teach it at all, they need powerful direct experiences that allow them to introduce a topic and provide some context for it, a game or activity that helps the students learn a concept, and a debriefing in which the students ask questions and teachers reinforce student learning. All of this must occur in a block of about thirty minutes or the teacher will determine that it takes too much time. The balance between the needs of the teacher for accountability, the needs of the students for a direct and interesting experience, and the needs of historians to render an authentic account of events is the place where I find the most professional challenge.

Introduction

When evaluating a game the needs of the teacher, student, and historian bring into play areas for criticism, but the constraint on play within the schools is the greatest challenge. Understanding the constraints helps to understand the circumstances for the design. Lack of time, interest in the subject matter, and understanding of the subject matter all prove to be challenges for using games in educational settings. Hopefully, children would find that the game is interesting enough that they desire to play it when they get home and share it with their peers and family members. The opportunity for the future of learning about the Civil War through gaming is the option of extending the learning offered through the school day or the cultural institution into off-school time through play.

Teachers use curriculum that help to set the context, provide learning extensions, define the debriefing, and provide for assessment support some games. Teachers accustomed to debriefing students after an educational experience;occasionally museum and cultural personnel do the same. The prospect of games emanating from museums without this prospect of debriefing gives museum marketers and those trusted with defending the museum’s brand pause to be cautious. Games that raise controversial issues or deal with multiple perspectives have no way to ask the player to debrief thus raising fears that only safe topics should emanate from an institution. This leads to a greater fear that cultural institutions may tend to self-sensor in order to be safe at the cost of interesting their audience or asking their audience to critically engage with issues.

The Role of the Historian

Historians contribute to the process of designing a gaming experience by providing three important aspects of the design sequence: fact checking, process identification, and curriculum collaboration. Fact checking is, of course, a historian’s greatest role to insure that the design team gets the story correct. Everyone wants his or her story to be told well with rich details that provide depth, with multiple perspectives to show sophisticated thinking, and substantial context to document its importance. The rest of the team brings talents from art, computer, education, music, and telecommunication backgrounds, but they may not share the understanding of the historical events or the commitment to getting details accurate. Historians are in a well-placed role to select enduring issues that each generation wrestles with and resolves within a democratic society.

Since games are best at helping the player to understand processes, the historian has an important role on the design team in identifying the process to be explored through the game. It is very easy for the historian to be distracted by the allure of a great story, but he or she must remain focused on tracking the best process that generalizes from the past to a game format. Ideally this process is something that the student will work with in the real world of civics or something the student will work with in their daily life. It is very difficult to get a multiple player game to show differing perspectives due to the lack of balance created by characters of divergent power expressed through wealth, race, and gender. The historian must communicate the idea of a process from the past, while allowing students to glimpse the stories of other people and how they relate to society.

Finally, the historian’s role in curriculum creation should not be overlooked. Connecting the most recent scholarship on a topic and understanding the historiography on the subject supports the educators as they strive to select the most important elements as they design units, lessons, and assessment tasks for students. These three ideas involve historians at the beginning, middle, and ending phases of game design and game production. As the historian shares information with teachers and students they begin to understand how this story is connected to other events and circumstances. The historian’s ability to generate excitement for exploring the past is contagious as the teacher and students pass this game to their peers and families.

Opportunities and Challenges

Visitors to museums and historic sites and school students can engage in interactive history-themed games to learn historical, geographic, economic, or civic processes. Students take the opportunity to learn prior to visiting, on site, or when they return from the site or school. More importantly they have the opportunity to play and replay the games before sharing the game with their friends and peers. As a marketing tool these games can help a historical site establish followers who become interested in the content prior to making a pilgrimage to the site. Every year teachers start from scratch with a new group of students to create interest in content that may seem distant, abstract, or remote. Games offer teachers or museums the ability to make students and visitors experiences content material as immediate, concrete, and present.

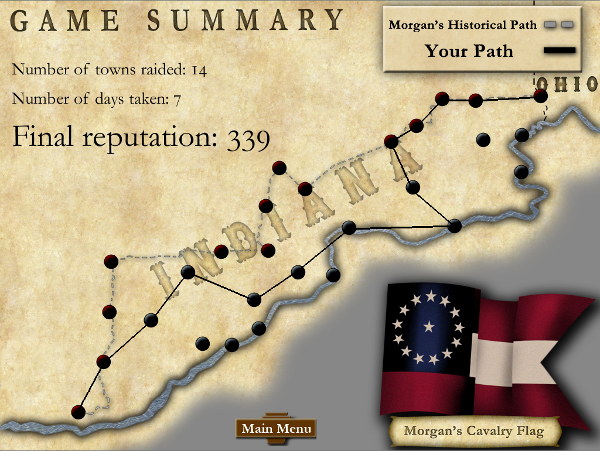

Teachers must deal with inherent challenges in incorporating gaming experiences into their classrooms or selecting them for use in museum programs. When teachers select educational games for the classroom, the games must be keyed into academic standards, and they must have measurable knowledge outcomes in subjects such as history, geography, economics, or civics. Next the teacher has a finite amount of time for play; for example, the Morgan’s Raid video game was designed so that teachers could introduce the Civil War one day and the following day the students could play the game with a minimum of instruction — in less than twenty minutes. This leaves the teacher with ten minutes for debriefing and questions. Sound effects even though important to students can be turned off so that the classroom does not become deafening. Accurate content must be delivered that is interesting enough that students will want to replay the game. Because of the age of the students, teachers will not select games where students are rewarded for killing people.

Interactive History

Narrative-driven solutions are not appropriate for games, but the phone application is very good for telling a story in short movies. Video is very narrative-driven and allows the flexibility of looking at multiple perspectives from a single phone by referring to multiple quotations from primary sources and examining different characters present on a battlefield at the same time. This allows the perspective of the North, South, and non-combatants to be understood as point-counter point. While I have not seen a counter factual history produced as an application, I am sure that it would be easy to speculate about what might have happened at a site if events had been slightly different in the form of an application. For example, if the Iron Brigade had not held at Gettysburg on the first day, the South might have swept over the Union position at Cemetery Ridge early in the day allowing the South access to the high ground.

A more interactive approach for classroom students would be for them to gather evidence from the battlefield to provide evidence of their construction of knowledge. They can take pictures with their cell phone, record information from docents, and narrate their understanding of events. Visitors do this type of collecting of information all of the time; for example, I wanted to see where all of the Indiana troops had fought across the battlefield at Gettysburg. I could have taken photos of each one of the battlefield markers after finding its location on a battlefield map anddownloaded it to my smart phone. I could then havetaken pictures of the text on the markers, which led me to find amazing stories that I had never heard before incised by the veterans who erected the monuments.

The Power of Place is the Real Thing

In learning a concept people need first enactive experiences, followed by iconic experiences, and concluded with symbolic experiences. A virtual experience like a game or video never takes the place of a direct experience, but it does allow a greater audience to become attracted to the site. A site visit is an enactive experience while a game works at the levels of model building allowing a student or visitor to create a mental model of how the process works. Many teachers in the elementary or university classroom attempt to skip directly to the symbolic level leaving their students unprepared for important basic experiences prior to accumulating massive mounds of symbols. Without the foundation of place, knowledge is built without the benefit of experience.

Complex Historical Processes

Games are an integral part of the interpretive experience and educational experience. Just as we would not rely merelyon quotations from journals without using other methods in our galleries or our classrooms, we do not rely exclusively on games to teach the entirety of a curriculum or to carry our interpretation. A comprehensive curriculum or interpretive plan exploring multiple perspectives prior to and after game play is imperative to insure that complex historic figures do not become one-dimensional heroes or villains. The design of games requires the designer to look at the fundamental process that exists in history to distill the element of fun. A clean and elegant design is the goal, but a complex historic process is just a complex process if the game element has not been rendered from it. A good game never tells a story even if it is a simple adventure story; a good game always examines a process and engages the player in decision making. The visitors/students engage in games designed to meet their needs and move them to the next level of their understanding by considering where the members of the audience can make decissions.

Historical Context

The gaming experience builds historical context by starting with the landscape of the period and recreating the built environment through architectures including both facades and interiors. Interiors communicate the values and economics of the home front from interior design to artifacts and include art and music. When constructing the personalities that inhabit this space, clothing, grooming, historical photos, and written descriptions from primary sources all build human qualities into the characters. Historical context is, however, window dressing for a well-balanced game, but for the designer and developer of a game for school or historical sites it must be accurate and as well researched as any scholarly monograph. Overture, intermezzo, and finale sequences all help to set the context of gaming situations.

Ron, I really like the design tension you point out between your interest’s as a historian, the reality of the classroom management needs, content coverage needs, and time constraints of elementary school teachers and the things that students will find interesting and engaging. All too often people who want to make games start by just thinking up what they think would be a cool game, but as you demonstrate, the real design challenge here involves mapping out the different constraints that exist around the situation in which you are designing for. The design challenge for educational games is not about making great games, it’s really about making great games that fit with in the very tightly defined constraints of particular learning contexts.

I like how you have specified the role of the historian in a game design project. I want to push back on it a bit on the idea of “getting the story correct.” I can see that as one notion of what history is, the correct story, but I generally come from the perspective that the most valuable thing historians can bring to the table is helping learners understand that histories are made, that is they are authored and the come from points of view. So I think there is a lot of possibility for the role of historians to be to help make history much messier. Have people work with primary source material and construct their own interpretations, or use evidence to refute, refine and revise competing stories of the past. I’d be curious for your thoughts on that.