My intention for this post was to write something specific and reasonably authoritative on how the character of Stede Bonnet as seen (as performed by means of, really) in Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag differs from what we know of the historical Stede Bonnet, and what I think the difference means. That kind of analysis would serve as a very useful example of how, within my model of text as ruleset, player performances of ubiculturality in the Assassin’s Creed franchise embody both games’ potential for critique and the pitfalls of uncritical reception. This post would have functioned both as a companion piece to David Hussey’s wonderful Assassin’s Creed Week posts, and as an extension of my “games precede the humanities” argument.

I planned, that is, to show that if you play ACIV without thinking about how it fails to do justice to the complexity of history, you end up thinking that the real Stede Bonnet must have been a likable fellow, whereas if you play ACIV with the complexity of history in mind, you end up with interesting questions about Stede Bonnet, and new creative tools with which to find the answers.

Time at the end of the semester has got away from me, though, and so instead of attempting a half-baked version of that post, I want to try to open a conversation about Stede Bonnet and about the Assassin’s Creed franchise in general. Quite possibly no one will respond, but I’m guessing that the game is good enough, and popular enough, that at least a little bit of valuable discussion will ensue.

So, in order from least to most abstract, here are the questions to which I’d love to hear others’ answers, in particular as they relate to the issues David raised back in February:

- What are your impressions of the character of Stede Bonnet in ACIV?

- How true to our information about the real Stede Bonnet do you find the character to be?

- What effect do you think Wiki articles like the one linked at the start of this post have upon the critical discussion of this game or any game?

- How important is it to play a game like ACIV critically, keeping in mind the complexity of the real historical forces involved?

- To what extent, when we play ACIV, are we doing history?

While I have not played the game yet, and have little awareness of the historical figure, I’m still going to try and answer that last question. YAY, opinions!

I think historical games such as Assassins Creed should be seen as relatives of counter-factual histories. In both cases the facts of history are there, surrounding the implanted conceit. They can be decent learning aides, but we are not ‘doing history’. The audience is usually smart enough to know the distinction.

That said, they can be beneficial learning tools. The games really allow you to get inside a historical environment. The situation is usually very well researched. As a basis for further reading, the Assasins Creed games are a good place to start.

I like the comparison to counter-factual history very much, Ross! I guess I think that question of “doing history” comes down to definitions, but I also think that in one very important sense, performing within a historical ruleset needs to be looked at as an activity that’s highly analogous to what we more usually think of as “doing history.”

I agree that historical recreation such as this is akin to ‘doing history’. I’m probably getting a bit too philosophical here, but I think there’s also an element of objective vs subjective consumption.

If you were really ‘doing history’, you would be defining your environment first-hand. Playing a game like this, or indulging in a counter-factual history, you are aware that the situation is being presented to you by a third party. And, in a roundabout way, I have brought us to Inception. Ubiception.

Can you unpack “defining your environment first-hand” a little? I guess in accordance with the argument about games and the humanities I’ve been shaping I’d say that the possibility-space for doing history is always handed to you by the tradition. ACIV is a minor offshoot of that tradition–in some ways like a bad student paper written with an encyclopedia as its source: playing ACIV, to the extent that one engages thereby in historical inquiry, would be like reading that paper, but as you’ve already pointed out, that might very easily be the beginning of a “truer” kind of historical inquiry that takes the player back to the primary sources.

What I mean is that in order to properly do history, you need to be able to make your own choices about what you want to do, and how you want to interact with your surroundings. The environment should then react in a way that seems authentic or realistic.

The Assassins Creed series has been really good at opening up the environment, but it is far from a sandbox. It is still concerned with the major storyline to the point that you are less interested in exploring. This is because, even if there is more to see away from the main plot, there is less to do.

Got it. That’s a really important distinction, and a good point. Makes one salivate for an Assassin’s Creed that plays like a Bethesda game! More verbs! More verbs!

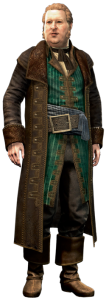

I find Ubisoft’s interpretation of some of the reported “facts” about Bonnet interesting.

Bonnet’s turn to piracy is generally reported as being the result of his unhappy life on a Barbadian sugar plantation. His inability to command a ship is also apparently related to his fondness for books, and a general inexperience with sea life.

So Ubisoft takes the disgruntled husband route- the turn to piracy is Bonnet’s avoidance of a nagging wife (who seems to have died in 1715, two years before Bonnet turns pirate). He’s certainly a bumbling seaman and a clueless pirate in the game. Is that the only way to interpret Bonnet?

How about the only pirate among himself, Teach, and Hornigold (and Kenway, for that matter), to have actually grown up in the Caribbean? On a sugar plantation, no less? On an island so close to Spanish South America, and so far from the centers of British colonial power in the Caribbean? Are we to believe that Bonnet was a bookish simpleton who knew nothing of naval commerce, slavery, and colonial government? Wouldn’t knowledge of these subjects greatly enhance a career as a corsair?

Although I’m critical of Ubisoft’s interpretation, (and in Travis’ debt for pointing out such a great classroom activity). I’m appreciative of AC IV as a useful tool for teaching the thoughtful analysis of sources.

That seems like a really great to place to start doing “real” history, Jeff, and a nice way to encapsulate the AC franchise’s most basic affordance in the area. Thanks!