« Those who study history are concerned with the occurrences of passed times; those who conceive time as history are tuned to what will happen in the future. » — George Grant, Time as History

When we play at History, are we playing the past, or the future?

As players of history-themed games, we are often called to be actors in a simulated past time, or context. Yet when we are called to « make history » or « rewrite the past », how does our idea of History change? If history is our present-day view of past events and people, what happens when we take on fictional « destiny-making » roles for a spin – roles which, by definition, are meant to « leave their stamp on History », and shape the future?

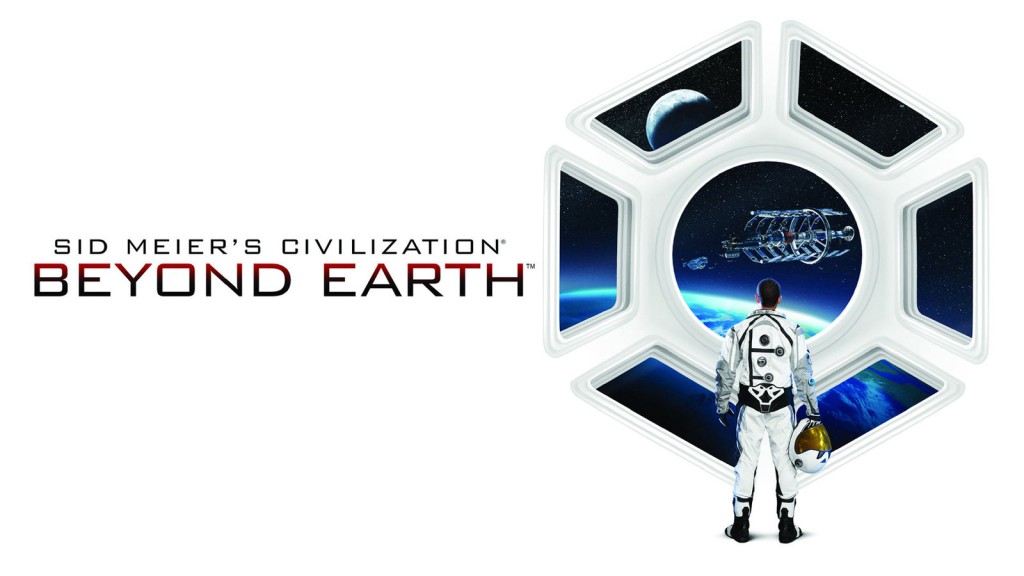

« Making History » is a popular slogan in the marketing of history-themed games. In the world of console gaming, the entire Assassin’s Creed franchise is most visibly positioned on this promise; the release of Assassin’s Creed: Unity in 2014 makes the call of History its core marketing message. In the computer-gaming world, Sid Meier’s Civilization franchise has been a defining force in the play of popular history, History-channel style.

Indeed, you’d have to be living under a rock to not see how games have become, in the past two decades, a phenomenal entertainment vehicle for popular history. The different genres of video games offer differing entrées to the popular history theme-park: action genres offer situated historical reenactments, strategy genres help armchair statesmen play out old imperial ambitions. The recent revival of the point-and-click video games attests to the enduring popularity of storytelling – a key feature of popular history – within game formats. In the world of board games, wargames simulate historical military conflicts with experimental models of war, and German-style board games (or Eurogames) offer simple, yet strategically deep, social play spaces with rich historical themes.

Outside the world of games, we should also mention historical reenactment societies – most famously the Society for Creative Anachronism – which, alongside providing fantasy escape for the masses, supplies costumed extras for period-based feature films and… History Channel documentaries 😉

These different genres of play media are so many lenses from which popular history can be expressed. Beyond the entertainment value of these play experiences, teachers and academics have begun to take note of the educational value of history-themed games, and play. Whatever games and reenactment lack in historical method, they compensate by stimulating historical curiosity, and empathy. With the appropriate critical apparatus, games can become a powerful tool for teaching history in the classroom, alongside traditional educational approaches.

I have made a point so far of emphasizing the « popular history » aspect of history-themed games. For this, I believe, is perhaps one of the greatest contribution of games to our understanding of History. In short, games, like no other medium, have expressed the assumptions of popular history through its different genres, which, taken together, tend toward one type of history: l’histoire-action.

I use this French expression, best translated as « being historical », in contrast with another form of History, l’histoire-connaissance, the learned study of history. As we will see, these two concepts of History are two entirely different creatures. The medium of games, overall biased toward popular history, entertains through l’histoire-action, with occasional niche crossovers into l’histoire-connaissance. Finally, though l’histoire-action and popular history are not the same thing, we will see how games bring out their mutual affinities to the fore.

In this article, I want to examine how games are changing the culture of popular history. To be sure, games are not easy to define, but they structurally share a quality – player agency – which introduces an important new variable in history as an entertainment genre. My main argument is that this novelty of player agency, introduced by games, forces us to examine some of our most important assumptions about history: historical agency and process. Specifically, one sub-genre of computer games – so-called « 4X strategy games » – expresses ideas of progress and « historical destiny » which underpins our view of history in its game mechanics. In my view, the 4X genre makes a clear breakaway from the typical storytelling format of popular history, by putting the player in the driver’s seat of « historical process ». This focus on historical process in an entertainment format, in turn, marks a shift toward what I will call the « technological view of History » in the popular imagination, with its attendant implications.

The primacy of storytelling

To the specialized reader of History and the academic historian, history is a fairly complex creature. We know that History was born in Antiquity as a literary genre. Herodotus, often called the « father of History » gave birth to the genre with his Histories. His ambition was to report the notable deeds and ways of Greeks and non-Greeks, and record them for posterity. Ostensibly, Herodotus was investigating the causes of the medic wars; in actuality he acted as a reporter and mythographer for all manner of peoples, stories and events, all weaved together in an all-encompassing narrative, one epic road-movie. His successor, Thucydides, invented historiography. Thucydides was concerned as well with the causes of war, but he stuck to his guns rather than succumbing to the call of adventure. With a single-minded focus, he sought to root ought the causes for the civil war that was tearing apart the great Greek city-states. In the process, he laid the foundations for the systematic study of the past, using tools such as chronology, anthropology, and the critique of sources.

Herodotus’ and Thucydides’ roman successors did not take up the torch of Greek inquisitiveness. Rather, History in the roman period took on a more official purpose. Historians such as Livy, Suetonius and Tacitus created a template from which all events of the past were to be judged, the « old roman ». Their accounts of the origins of Rome, the rise of the republic and the emergence of the Roman empire would be written from the vantage-point of their ideal, for purposes of patriotism. Notably, many historians of late Antiquity held priestly offices: Tacitus was a quindecemvir, a « member of the priestly college in charge of the Sibylline books », and the Greek-born Plutarch was a priest at Delphi.

In short, in the Roman period, the genre of history took on the function of l’histoire-action, history as political discourse. Historical narrative would from now on mainly serve the purpose of legitimizing power, rather than truth telling.

This abyss between politics and truth in History, many would argue, continues to this very day. Unfortunately, the pursuit of academic history is not free from the imperatives of power, and so we cannot say that historiography is, in itself, a disinterested science. But rather than debate the politics of history, I would like instead to highlight the role of popular history in furthering l’histoire-action, because it is at once obvious and non-obvious. Obvious because popular history uses storytelling rather than historiography, and l’histoire-action is concerned with creating foundational myths. Non-obvious because popular history is pervasive, in documentary and fiction genres alike. Like Herodotus, popular history purports to be a true witness of events and people’s lives, and it is more difficult to detect its political biases than in academic history, which is often at pains with making its purposes explicit.

The “transparent” quality of narrative makes popular history into a somewhat fuzzy concept. As noted in Wikipedia:

Popular history is a broad and somewhat ill-defined genre of historiography that takes a popular approach, aims at a wide readership, and usually emphasizes narrative, personality and vivid detail over scholarly analysis. The term is used in contradistinction to professional academic or scholarly history writing which is usually more specialized and technical and, thus, less accessible to the general reader.

As I am wont to emphasize, popular history has many purposes – to educate, to commemorate/memorialize, to entertain – but all turn around storytelling and a broad audience of non-specialized readers, TV watchers, film goers. These traits inherent to popular history bely its affinities with l’histoire-action, history as a political activity.

A new era for popular history

The rise of gaming culture throws an interesting wrench into this scheme of things. For one, games, and video games in particular, have become the leading form of entertainment around the globe. For those who have a story or message to share, games are a cultural force that one cannot ignore. On the other hand, as attested by the narratology/ludology debate in game scholarship, the central place of the player in the game form makes the emphasis on story problematic. In other words, if the medium of games has the potential to communicate popular history to new audiences, the form of games fractures popular history into storytelling genres and play experiences.

In games, traditional forms of empathy through character identification are supplanted by player agency. The many game genres listed above take the player to be the main character of the game « plot » , emphasizing or deemphasizing story in the process. Of all these genres, it appears that the main game-changer for popular history is the strategy game.

Strategy games are a venerable genre of games – classic strategy games such as Go and Chess have long been seen as a metaphor for war. Instead of calling upon physical skills, in strategy games the player must use intellectual skills to achieve victory. Because of their abstracted quality, strategy games helped cement the view of games as formalist systems – a competitive framework with clearly defined objectives, in which all possible player moves are bound by rules and finite game elements.

Computers added a new dimension to strategy games: a simulated universe, executed by a machine. In a larger sense, computer strategy games can be seen as metaphors for the power of computers, and the power of information. Typically, they provide the player with an omniscient view over a theatre of operations, and allow him or her to interact with various game elements, and take the game’s simulated systems into consideration when making decisions. These structural features of the strategy game – an omniscient view, the role of information in decision-making, and use of intellectual skills – create a new entertainment form which is largely concerned with conveying a top-down power fantasy.

The strategy genre has developed, over time, into many identifiable sub-genres: the economic and management simulation, the wargame, the turn-based strategy game, the real-time strategy game, etc. These sub-genres are the main way games are marketed to audiences today. But game systems and mechanics have not been, in themselves, the sole defining features of these genres. Common narrative themes have been key ingredients to the success of computer strategy games, two of the most popular being historical civilization, and space conquest.

The 4X genre

The similar game progression concepts shared by these two recurring themes, or « skins », point to a common ideology. The obvious connection, is that both historical civilization and space conquest themes express the continuity of the historical process, originating in the past and extending into the future. Yet, this generality does not tell us anything about the blend of theme and mechanics used to illustrate the historical process. Game designers who sought to give expression to the historical process in games, knew that the success of the genre depended on how well the philosophy of history was nested in the play experience.

In my opinion, this « trans-historical » play experience receives its fullest articulation in the 4X strategy genre. Best known as « Civilization-type games » (after Sid Meier’s landmark franchise) the 4X strategy genre is sub-genre of strategy games that focuses on the process of building an empire, or civilization, in both time and space. This dual axis of time and space remains the defining feature, and central appeal of the genre. 4X strategy games beset the player with the premise of a culture group setting foot in an unknown and often hostile world, trying to survive and thrive against competing fledgling empires. As the name 4X suggests, the player must predominantly engage in four types of activities, in order to achieve the specific victory conditions of the game: eXplore, eXploit, eXpand and eXterminate.

A typical game begins with a few exploration and settlement units, with which the player must settle his colonists. Once a settlement is established, the player will generally pursue the four types of activities of the 4X in simultaneous order, in view of his resources, his overall plan, and the events and challenges posed by the game system or other players. 4X games are typically turn-based games, allowing for players to implement a specific configuration of actions, and executing these actions simultaneously once they have been planned out.

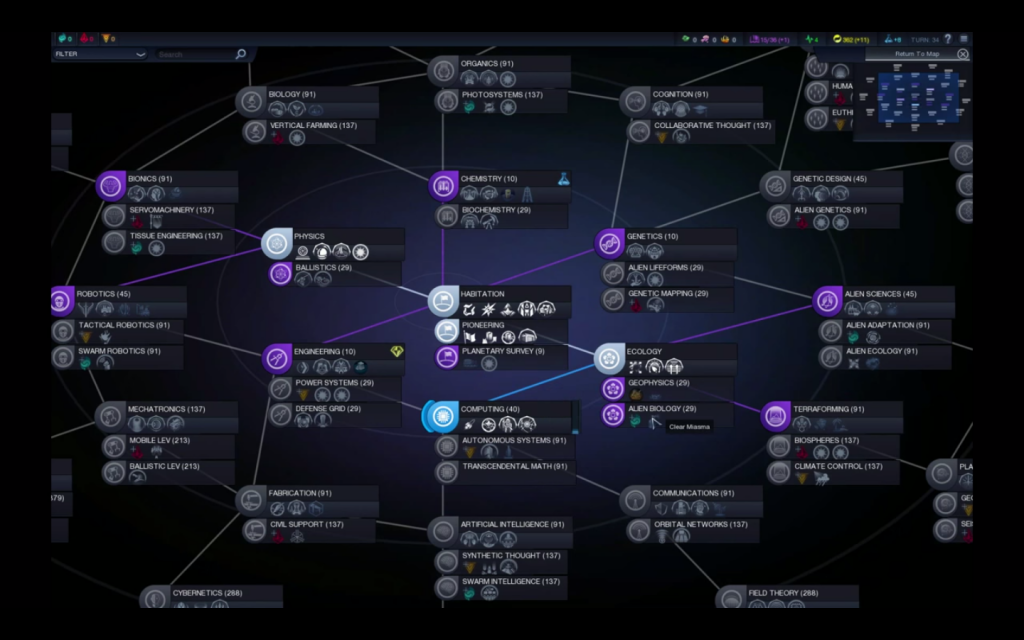

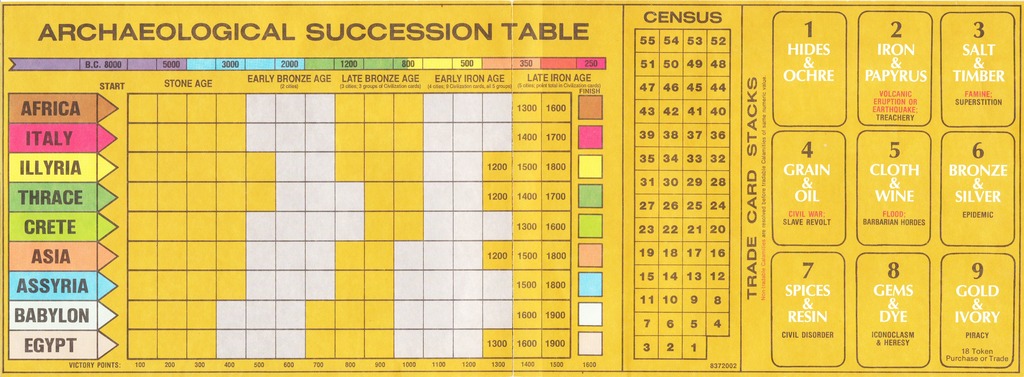

The specific flavour of 4X games usually comes out in the implementation of theme through innovative gameplay mechanics. One early innovation was the technology tree, a progression mechanic centred on the activity of research and strategic advantage through technology. Originating in Francis Tresham’s Civilization board game, the tech tree mechanic was popularized in Sid Meier’s Civilization series, and has become a standard feature of the genre. Rightly criticized as overly-deterministic, the tech tree has undergone a conceptual overhaul in some recent titles (cf. Pandora, or Endless series), for more varied gameplay progression.

Early-on in the development of the genre, game developers discovered that the linear progression, in itself, did not give the player a sense of historical progress. The upgrades of the tech tree, while enabling the player strategically, did not account for cultural development and achievement. Thus, Civilization-type games implemented clear milestones in the form of « Ages », based on cumulative achievements on all fronts – technological, economic, military and cultural. These Ages borrowed the nomenclature from popular history- the Classical Age, Middle-Ages, Renaissance, Modern, etc – to situate the player’s progression in a trans-historical context.

In 4X games, players play not as a specific character, but as a faction. Borrowing heavily from the role-playing genre, factions in 4X games have the dual function of providing identity, and creating asymmetry. All factions have standard units, with individual faction « colourings » in the form of visual style and specific bonuses and penalties, abilities and handicaps. In many games, each faction might have special units, that provide strategic advantage in one key area: political, diplomatic, economic, military, cultural, etc. The asymmetric conditions of warfare and development often force the player to focus on creating strategic advantage with the « givens » of his culture group, and of the land he or she has staked.

The technological view of History

With these standard features in mind, I would like to focus on how the 4X genre expresses the historical process. An analysis of the core gameplay of the 4X genre reveals that it is imbued with the worldview of technology. The four core player activities of exploring, expanding, exploiting, exterminating can be seen as interlocking philosophical gears of modern technological mastery, projected onto civilizations of the past and the future. Wikipedia summarizes these 4 activities as such:

Explore means players send scouts across a map to reveal surrounding territories.

Expand means players claim new territory by creating new settlements, or sometimes by extending the influence of existing settlements.

Exploit means players gather and use resources in areas they control, and improve the efficiency of that usage.

Exterminate means attacking and eliminating rival players. Since in some games all territory is eventually claimed, eliminating a rival’s presence may be the only way to achieve further expansion.

This language is widely recognized by philosophers as the driving force behind the European Age of Discovery, and emblematic of modern technological society. In his celebrated essay Time as History, Canadian philosopher George Grant sees Nietzsche as the philosopher who best understood the meaning of technological thought:

In his work, the themes that must be thought in thinking time as history are raised to a beautiful explicitness: the mastery of human and non-human nature in experimental science and technique, the primacy of the will, man as the creator of his own values, the finality of becoming, the assertion that potentiality is higher than actuality, that motion is nobler than rest, and that dynamism rather than peace is the height.

While it would require a full philosophical dissertation to explore Nietzsche’s diagnosis of our will to mastery, my intention has been to look at the 4X genre as a popular expression of this philosophy. Of course, 4X strategy games have a deterministic view of technology and history. I join my colleagues of Play the Past in singling out simplistic views of history. Yet, in the spirit of Nietzsche’s critique, I feel the charge of determinism somewhat misses the point. The developers of the Civilization franchise never denied that the game had a simplistic view of the historical process. More fundamentally, popular and academic history do not have the same goals: one is historical truth, the other is historical myth – l’histoire-action.

Until the advent of games, the only visible part of the popular history iceberg was the storytelling genre. Time as History, or « historical process » enters into popular history with the advent of Civilization-type games, and their progression mechanics. Since player agency is at the centre of the game medium, games allow us to see l’histoire-action, the « stuff of history », more clearly than other forms of popular media.

The preponderance of space colonization and fictional civilization themes in 4X titles is therefore no coincidence. In 4X games, we are called upon to manifest the Age of Discovery, as endless recurrence. A game of pure horizons, with no other horizon than becoming. Once upon a time, in some distant past, or future…

References

George Grant, (1969) Time as History.

Matthieu Triclot (2011), Philosophie des jeux vidéo.

As a gamer and a recovering historian (BA in History/PoliSci, MA in Ancient History), I really enjoyed this article. Never before have I found Herodotus, Civ and the SCA all discussed in the same place. This was a wonderful read that reflects a lot of my personal history. And future next week when Civ Beyond Earth comes out.

What are your thoughts on classical ones?