Jessie Craft teaches Latin and ancient history at Winston-Salem Forsyth County Schools; he recently published ‘Rebuilding an Empire with Minecraft’ in CAMWS Classical Journal, Vol 111.3, Feb./March 2016 based on those experiments in his classroom.

Introduction

By now, Minecraft has established a solid reputation for itself in academia. The positive results of its implementation are evinced in publications (see Bukvic et al, ‘OperaCraft‘, Graham, ‘HIST3812a‘, List, ‘Using Minecraft to Encourage Critical Engagement of Geography Concepts‘, and Schifter, ‘Minecraft as teaching tool‘) and systemic changes. For instance, a few years ago Minecraft created a modified version directed specifically at classroom implementation which they called MinecraftEdu. MinecraftEdu met with such success that Microsoft, after acquiring Minecraft, also purchased MinecraftEdu renaming it Minecraft Education Edition . Thanks to these publications and modifications some people, like James Delaney, a college student and director of BlockWorks, are calling for changes in the way we conceptualize Minecraft altogether, ” People have to stop thinking of it (Minecraft) as a game. It’s a CAD tool, and as such it is the most widely used one in the world.” (http://www.archdaily.com/781644/how-minecraft-is-inspiring-the-next-generation-of-young-architects)

During all of the changes that Minecraft was undergoing I was working diligently not only to teach my own students using MinecraftEdu but also to collect the necessary empirical data to begin to substantiate the anecdotal claims made by Beth, Delaney and others. For my implementation, I have sought to reproduce ancient Rome with the aid of my students in a project I call Ars Romana.

Creating the Virtual Learning Space

After researching many models of ancient Rome, DigitalAugustanRome.com provided me with the basic city outline and elevations and Scagnetti’s Roma Urbs Imperatorum Aetate map (2006) served to determine the location and orientation of all the major archeological sites. The third party program WorldPainter (http://www.worldpainter.net/) allowed me to create a blank Minecraft map at 5K blocks N-S by 5K blocks E-W and then use Scagnetti’s map as an overlay to mark major buildings and trace roads.

Once the terra-forming was completed, I sought to heighten the sense of immersion, a concept discussed at greater length by Christiansen and Craft, by changing the game textures to more nearly imitate some of the actual stones, mosaics, paints and stuccoes of ancient Rome.

| a. | b. | c. |

a.) Texture of entablature with marble dentils and colored festoon

b.) Opus signinum – common floor tiling

c.) Dado – common sagging leaf pattern

Along with the textures, I began translating the material names into Latin so as to incorporate a linguistic element into the greater sense of immersion. Ultimately, the goal was to make a world in which almost every aspect the students interacted with invoked feelings and ideas of ancient Rome.

The Project

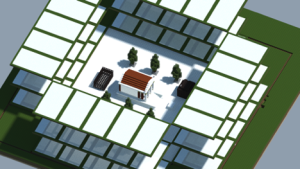

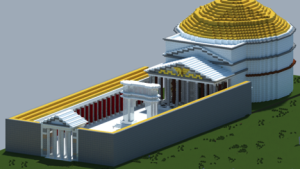

Given the total size of Rome, it was clear that this project should be broken into systematic units which students would address each year. During the first year students created temples. To begin matters, it was necessary to give students exposure to constructing in Minecraft before moving on to the graded project. I created a sandbox with a model temple in the middle which students had to replicate as accurately as possible on their respective platforms.

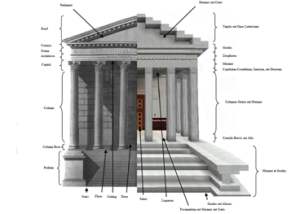

During this time, students were also tasked with researching their temple in primary and secondary sources. To guide students along they received a list of some of the most prominent and relevant sources for this endeavor and a questionnaire seeking measurements, building materials, building style, information regarding deity worshiped in said temple, who commissioned the temple, etc. Part of the research required students either to print off pictures of any extant remains, existing building plans, or photos or to sketch their own floor plans using the information gathered from their research. To help students maneuver through the unknown Latin terms for the materials they would use to construct their temples and to help them determine which materials were destined for which purpose, I created a diagram depicting a sketch of a reconstructed temple with a Minecraft approximation.

Having completed their research element, students were to get everything cleared by me and then begin building. It was great watching it all unfold. There was online collaboration between partners eager to get the angles of the pediment just right. You could see students shuffling through plans discussing which was the more accurate representation. Many students came to me looking for a quick translation into Latin of specific items they needed for building only to be shown an online Latin-English dictionary instead. Students took risks in adding color to buildings.

Better yet was witnessing those kids who usually struggled with the rigorous grammar approach of Latin now soaring with their virtual models. The students’ different learning styles and unique approaches to problem solving made themselves most apparent during this project. Each day in class kids inquired if we were heading to the Media Center to work on Minecraft and showed real disappointment the times I said no. It is true that not every student was so excited to work in Minecraft, and it is also true that not every student’s work was accurate enough to make it into the final model. However, the overall outcome was a success and continues to be so. To better substantiate these claims, I performed an analysis of the data resulting from two iterations of this project which can be read here http://www.wsfcs.k12.nc.us/Page/105083. One of the more interesting results, in my opinion, was that the girl players actually learned more from the experience than the boys. I gladly welcomed this finding as it flew in the face of those old adages about girls not being good at or liking video games or that boys are more spatial and hands-on learners.

Rationale Behind the Project

Much of my decision to recreate ancient Rome revolved around the lack of reliable and available 3D cultural heritage models. Many of the existing models or reproductions of ancient Rome are either outdated or have been romanticized behind reality, think Gladiator starring Russell Crowe. By creating our own, we could be sure that the academic accuracy was there and current, even if the blocky nature of Minecraft prevents us from reaching total spatial accuracy. By building our model in Minecraft, it is very simple to update a building or site according to the latest publications regarding new archeological finds and theories.

The ability to change the game’s textures granted us the opportunity to experiment with the polychrome reality of ancient Rome. Those buildings were not all a pristine Carrara marble or travertine, which is most often how they are depicted in other models. Very few scholars experiment with polychrome in their published models since so little evidence for precise color remains and conjecture without sufficient supporting documentation is usually problematic for scholarship. In our project we do not have such restraints so the students get to explore with colors and thus see how Rome may have really looked without fear of scrutiny.

Availability and access to the existing accurate and researched 3D models is also an issue. The physical models are located in Rome and the 3D virtual models are heavily guarded by the professors and institutions who created them. Even if the creators of these heritage models were not opposed to public viewing of their work, there are presently no central archives to store them, and the regulations on metadata and scholarship for these models have not yet been constitutionalized (See Koller et al ). Since I believe firmly that cultural heritage 3D models should be available for all, as we complete this model and others we will release them to the public free of charge at planetminecraft, the largest share-site for all things Minecraft related.

Anachronisms are often very prevalent in the mind of students and the general population when imagining ancient Rome. Therefore, it is important that students and the general public have access to a researched model of ancient Rome’s likely appearance during the most studied period — late Republic to early Empire. Without fail, each year students are blown away when they learn that the Coliseum (Flavian Amphitheater) did not exist during the times of Caesar or that the Roman Forum had a noticeably less cluttered appearance during the 1st century A.D.

First-person immersive experiences, however, likely are the true reason behind all of this. Minecraft allows us to work on our models in a 3D environment designed to give players a greater sense of realism thanks to strong game physics and spatial dimensionality. We have the distinct opportunity, for instance, to approach a building in-game and experience what feelings and emotions its mass, architecture, colors and juxtaposition to other buildings and natural elements may have imposed upon the visitor and passerby.

Furthermore, the first-person immersion allows us to experiment with and comment on sightlines in building arrangements. This is very important especially during the Age of Augustus when his building programs started to come together as cohesive collaborations considering immediate environs which is to be contrasted to the heavy hodge-podge make-shift manner of building so prominent during the early and middle Republic.

With my Ars Romana project I hope to make the classical Greco-Roman world accessible and relevant to a broader and younger audience; I hope to teach my students in a thoughtful and meaningful way using the very technology they were born with; I hope to herald a new wave and generation of 3D cultural heritage architects whose experience in Minecraft will be the gateway to more complicated and sophisticated 3D modeling platforms.

~o0o~

To read the article from which this piece takes it origins, please visit here: http://www.wsfcs.k12.nc.us/Page/105083. For more photos and regular updates on the progress of Ars Romana and other projects I oversee for my students, please visit here: http://www.planetminecraft.com/member/magistercraft. As Chapman discussed in his article on Play the Past , we are still in the early stage of really opening an interdisciplinary dialogue in a concerted effort to hash out all of the possible implementations and implications inherent in creating 3D heritage models and using technology pedagogically. As such, I welcome any comments or concerns below; let’s keep the conversation going.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/DivusMagisterCraft/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/MagisterCraft

Planetminecraft: http://www.planetminecraft.com/member/magistercraft/