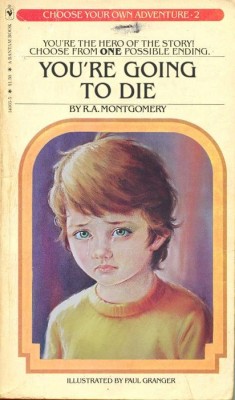

A True Story of Digital Heritage Hijinks and Augmented Reality Adventure Where YOU Write The Ending

Chapter 1: Rebuffed!

One of the most difficult tasks people can perform, however much others may despise it, is the invention of good games.

—Carl Jung

The year is 2008. The month is April or so. Katy Perry is kissing a girl, Fred Thompson is weighing his presidential prospects, and you are a hard working (and pure of heart) assistant professor at a large Midwestern university.

You are chatting with your friend Bill in the recently opened “NiCHE-space,” a term you find funny when spoken aloud. (Because a niche is a space, see, so it sounds like “street-road” or “room-room.”) You are discussing the upcoming “THATCamp,” a brand new “unconference” on the humanities and technology that both of you plan to attend.

“What does the C stand for?” you are saying.

“Camp,” says Bill. “The Humanities and Technology Camp.”

“Then why don’t they write it as ‘THATcamp,’ with a small c, or as ‘THAT Camp,’ with a space?” These are the questions to which hard working (and ruggedly handsome) assistant professors apply their genius.

“So we don’t present papers at this THATCamp,” you continue, “but we are supposed to come ready to talk about something humanities-y and technology-y?”

“That’s right,” says Bill. “No spectators. It’s like Burning Man, but with dongles.”

“So what are you going to talk about?”

Bill says, “Well, I’m only going to be there for the first day, so I’ll probably just talk about humanistic fabrication, lead a couple of workshops on naïve Bayesian learners and Arduino hacking, create an Eliza-style simulation of some historical figures, then build a replicating rapid prototype that can duplicate itself. How about you?”

You suddenly feel a bit like a naïve Bayesian yourself.

“Um, I have this blog…” you start to mumble. “It has this picture, of a robot, on it?”

“Hey, don’t be like that,” Bill says. “You have lots of cool stuff you can talk about. Those CHNM guys love you.”

So you shake off your imposter syndrome. Because there is something you want to talk about at THATCamp, something you actually are an expert on. Or at least have strong feelings about—and in the frontier days of digital humanities back in ought-eight, wasn’t that effectively the same thing?

“Actually,” you say, “I’d like to talk about using games to teach history and historical thinking.”

“That’s a great idea,” Bill says. “Do you mean simulation games, or role-playing games, or what?”

“Well, not simulation games,” you say. “I actually have this beef with simulations, which I will explain in a series of blog posts two or three years from now.”

“I’ll look forward to that,” Bill says.

“See, it seems to me that the rules and procedures of a game always trump its framing fiction,” you say. “What you learn in a game is what you do. Not what the game is ostensibly about. We can’t design good history games unless we really articulate what kinds of history and historical thinking we want to teach. And then we have to build outwards from those kinds of playful historical thinking, creating games and activities whose fiddly bits are historical sources, whose moving parts are historical ideas themselves.”

“Put that last bit in your blog post,” Bill says.

“I will!”

“So what would your game actually look like?”

“Well,” you say, “I’m thinking of it as a historical ARG.”

“As in ‘alternate reality game’?” Bill asks, for the benefit of anyone reading this conversation years later.

“Yes, or ‘augmented reality game,’” you say. “Plus ARG has the benefit of looking like ‘aargh,’ and I’m sure the whole ‘talk like a pirate’ thing will never get played out.”

“Never,” Bill agrees.

You start describing your idea. “Sean Stewart—he was the lead writer behind The Beast and I Hate Moths—says that the web and Google and email and social networking are all organized around two fundamental activities: searching for things, and gossiping about them.”

“And ARGs are a storytelling method built around those ideas.”

“Exactly. But isn’t that also what historians do? Search and gossip! We search for things and tell stories about them. We construct narratives out of bits of pieces of evidence scattered through the real and online worlds.”

“Hmmm,” says Bill. A kind of a shadow drifts across his features.

“So what if we designed an ARG that took the actual record of the past as its raw material? We could construct some kind of semi-historical mystery. Our players would investigate the mystery by doing research—not in some gated, mediated sandbox of pre-selected sources, but in the real world, with all its messiness and inconsistency. They would visit libraries and archives. They would gather evidence. They would construct the narrative, interpreting, analyzing, and debating the evidence they find. So historical content is not layered on top of some lame game activity; historical research is the game.”

Bill isn’t saying anything now, but you’re on a roll, so you just keep going.

“It would be a kind of mashup of I Hate Moths and Foucault’s Pendulum, but built on the strangeness and wonder of real history. Heritage and historical sites would be part of the game, because we’d have puzzles that can only be solved by visiting real locations. Riddles would refer to museum exhibits. We’d hide objects in parks and battlegrounds. Costumed interpreters at historical sites would make cryptic statements that turn out to be in-game clues. The players would get paranoid, but paranoid in a good way, seeing connections to history in everything around them. The game is pervasive, because the past really is everywhere.”

Bill still says nothing. In fact, he looks kind of perturbed.

“So… what do you think?”

There is a long pause. Slowly, Bill shrugs. “It’s an idea,” he says, without much enthusiasm.

The silence is awkward. And your whole THATCamp imposter syndrome comes roaring back. You really thought Bill, of all people, would get behind this. But no. Your idea must really suck, to be too out there even for him. “Yeah, probably a stupid idea,” you say, forcing a laugh. “ARGs. Heh. Too nerdy even for THATCamp, ha ha.”

Bill is unreadable.

You make your way to the door, lamely. “I’ll probably just talk about, um, Wikipedia,” you say. “Yeah. Can’t have too many conversations about Wikipedia, am I right? Or the pros and cons of blogging! That’s fresh…”

You escape the NiCHE-space and, crestfallen, close the portal-door.

BUT! Later that night, you are at your computer, trying to summon up a glimmer of interest in what Wikipedia “really means.” Suddenly, a window pops up on your screen, with an unnecessary “ping” and a giant font, like an unconvincing computer interface in the movies.

The window reads: “Ting Have Werewolfe Teeth.” Beneath this message is a countdown timer, with a year-month-date and an hour-minute-second readout running backwards into the past.

What… do… you… do?

To Be Continued!!!

I love this! Brilliant. And this isn’t far fetched at all. In fact, it sounds a bit like Myst, but based in the real world. Perhaps it could be setup in a sort of similar way, to provide a small amount of linear clue finding, etc.? I’m not sure. The format of this is great too.

Very cool idea. There are lots of ways to ground ARGs in the material, historical world. A bit of LARP would help, too.

Do you know Trinity University’s “Blood in the Stacks” game? Might be a neat one to keep in mind.