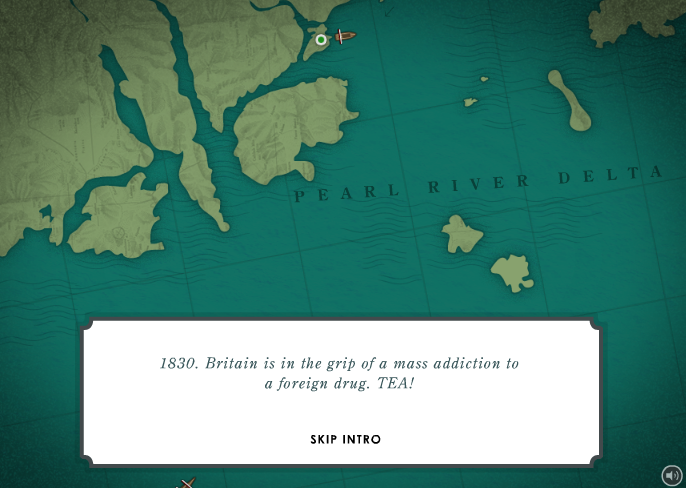

The premise of the game High Tea is simple: buy opium from Bengal, India, smuggle that opium into Chinese ports and sell it for silver, and use silver to buy tea for Britain. If players, acting as nineteenth-century British merchants, don’t meet the increasing demand for tea, then the mood of the English nation turns against them. The game ends when the mood of the English nation hits rock bottom (shown on a mood meter that only appears when players have not fulfilled a tea order in time). Players trade for ten in-game years, avoiding Chinese officials by limiting trade in risky locations and/or bribing the Qing authorities. After winning or losing the game, players are informed that the Opium Wars began shortly after the in-game timeline ends. Players also see the consequences of their actions in a post game summary, which includes the number of opium users created throughout the player’s time as a merchant. This is all demonstrated in the gameplay video below.

A few things about this game caught my interest: it was a collaborative success between game developers and museum professionals, it was distributed widely and provoked players to explore an unsavory part of history, and the game’s evaluation (including surveys, interviews, and focus groups) was released publicly. From conception to evaluation, it seems that this game was a success for both the developers at Preloaded (makers of 1066) and the cultural institution that commissioned the game, the Wellcome Collection.

Successful collaboration is possible!

High Tea, released on January 31, 2011, was made to accompany an exhibition on the history of drug use and perception at the Wellcome Collection called High Society. Developers at Preloaded worked with Danny Birchall, Editor of the Wellcome Collection website, and Martha Henson, Multimedia Editor at the Wellcome Trust. Birchall and Henson also collaborated with Mike Jay, the co-curator of High Society, to make sure that the game would provide content and themes relevant to the exhibition. The game was published on the Wellcome Collection website, seeded to the popular game site Kongregate, and ripped to many other sites without their intervention. It is important to note that allowing their game to be pirated (with Google Analytics still tracking game use, of course) was part of the Wellcome Collection’s distribution plan and accounted for over half of the game’s plays in the first three months.

In August of 2011, Birchall and Henson created an evaluation report for High Tea. The evaluation report and Birchall and Henson’s subsequent publications through Museums and the Web 2011 and 2012 are extremely helpful in understanding some of the challenges and best practices in creating games for museums. In these publications, which detail distribution methods, survey results, and interview methods, it is clear that High Tea provides players with an informal educational experience that, in some cases, inspired people to reevaluate their previous knowledge or do further research on the controversial subject independently.

Happy compromises in gameplay and history

High Tea is a good example of how gameplay and historical content can be merged to create a fun and (ahem) addictive informal learning experience. Play a few minutes or watch the video above to get a sense of the simple (but challenging!) strategic gameplay. However, as players mentioned in interviews, focus groups, and surveys (listed in the Wellcome Collection’s evaluation report), additional educational content within the game would have been even more beneficial for players. The following points are suggestions for improvement on the High Tea gameplay and distribution model:

- A better introduction: High Tea’s introduction includes the basic historical context for the game, and can be skipped immediately if the player chooses. Those who choose to read the introductory text cannot advance the text as they finish reading it and must wait for the text to cycle automatically, which is frustrating and might have resulted in more players skipping the introduction.

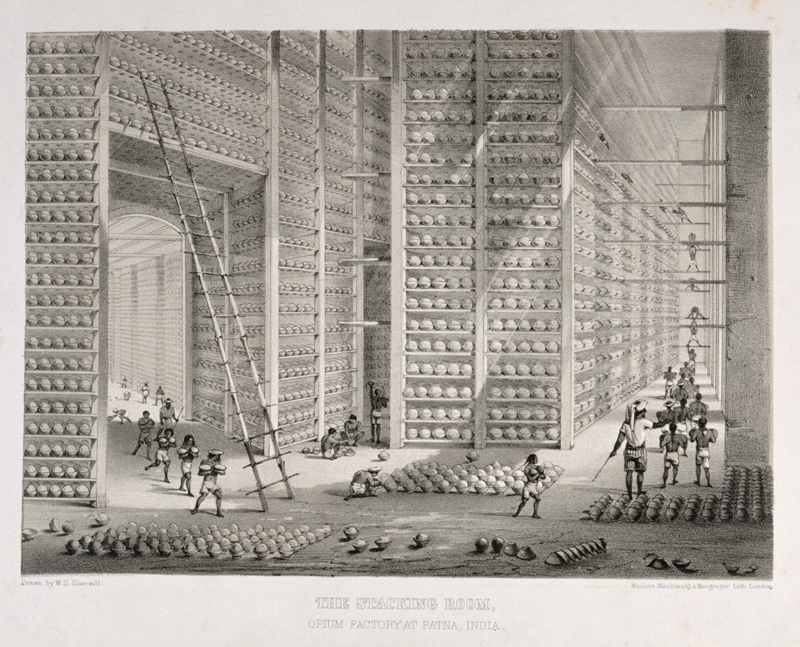

- Inclusion of artifacts: Most everything in the game is stylized or abstracted to the point that there is no discernible connection to the Wellcome Collection’s actual collection. I found myself wanting to know what was on display in High Society and wondering why even one or two artifacts weren’t included. I could not find an explanation or discussion of this issue, and I am curious if anyone else thinks it is beneficial or unnecessary to include artifacts in historical games (especially those made by museums).

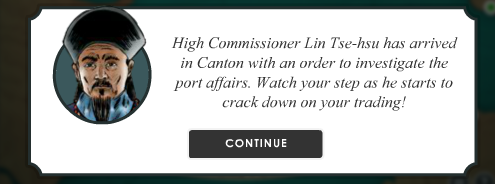

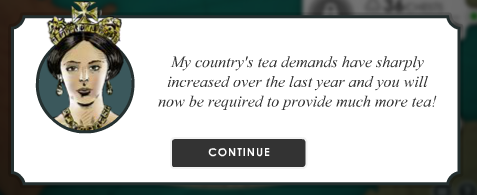

- Identification of historical figures: People speak to the player at key moments in the game, but some are left unidentified. Even when identified, their role within the history of the time period is not entirely clear. I could only find two historical figures who were identified, Commissioner Lin Tse-Hsu (Lin Zexu) and Captain Charles Elliot. Queen Victoria, however, was left unnamed.

- Dedicated space for conversation: The game does have a link to a survey inviting players to share their thoughts (the link now leads to page saying the survey is closed), but the Wellcome Collection did not provide a place where people could have conversations with each other and/or with educators or curators at the Wellcome Collection.

- Links to the Wellcome Collection: Since the game was made to be seeded and unofficially ripped to other sites, links to the Wellcome Collection website should have been included within the game in its various stages (introduction, main gameplay, and the game over menu).

High Tea is a fun and informative game as it stands, and its development and evaluation provide a model for other museums and development studios to implement when working together. These suggestions are really meant to highlight some priorities in the compromise between making a fun game and making an educational history game – giving the player choices of how to play and where to play, giving the player a place to continue conversation, giving the player access to primary source materials, and giving the player a chance to connect with a cultural institution.

Great article, very interesting to get a more critical perspective and suggestions for improvements to the game. Commentors on the gaming sites also wanted options to make it easier to buy or sell opium in greater quantities, the option to buy more boats, added multiplayer and sandpit modes and other suggestions for future versions. If only we had the time and money to do a sequel! People also pointed out that the trader should have been paid for the tea by the British, which is a fair point. It’s all about the compromise between factual accuracy and making a fun game, as you’ve pointed out.

I also hadn’t noticed that we didn’t name Queen Victoria! Well spotted. But even though some interviewees wanted more factual content, I do wonder whether others would have been put off. It’s a tricky balance. In our newer game, Axon, we’ve added pages that give background info and wikipedia links, but are in the process of evaluating that.

Just to answer a couple of other points, there were links back to the exhibition pages, not sure where they’ve gone! These pages had pictures of the artifacts etc and more information. Didn’t really occur to us to include these in the game itself.

We didn’t provide a dedicated space for conversation on our own site because that was provided by Kongregate/Newgrounds etc and we expected most of the traffic there. But engaging with those players more directly and bringing the curators etc into that conversation is a really interesting idea. Anyway, thanks for writing this, lots to think about.

I empathize with you that the practical limitations of creating games gets in the way of including great suggestions! Of course, limited funds, time, and resources will always be a challenge, but it’s also a good way to focus and develop goals, too. That in mind, I think my suggestion for providing a dedicated space for conversation on your site actually wouldn’t be as helpful as I had originally thought. Since so much of High Tea’s traffic was generated by other sites, it makes sense for Kongregate and Newsgrounds to be the location for conversations. Perhaps having curators read through those chat logs and even participating in some of the conversations would be a good solution.

I’m looking forward to hearing about how successful the extra background information and Wikipedia links are in Axon. One of the greatest things about the evaluation process with High Tea is that it can be used as a model for best practices – especially since the information has been publicly available and the process transparent.

I wonder if my hang up on the inclusion of artifacts is due to my background in material culture and the museum world – how beneficial is it to include images (artistically altered or not) of real artifacts? Would it be distracting if it doesn’t mesh with the artistic style or game play? Would it help the game reach the goals of engaging the audience and making connections with the exhibition and the collection itself? I want to say that including artifacts is always worth the effort, but I have no formal evaluation to back that inclination up!

Thanks for the comment and the hard work on High Tea – now I’m going to go play Axon!