This is a guest post by Dr Jack Orchard. Jack is Content Editor for the Electronic Enlightenment project based at the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, and holds a PhD from Swansea as well as a BA and MA from University College London. His PhD was on reading practices in 18th century women’s correspondence networks and he is currently researching the parallels between historical readers and contemporary video game culture. He can be found on Twitter @Jarona7

With Blasphemous II currently on the horizon, and the latest DLC, Wounds of Eventide, having been released in December of last year, I’d like to bring you some further thoughts on historical emotion in The Game Kitchen’s 2019 Metroidvania masterpiece, Blasphemous. Where my first piece, ‘Feeling History in Blasphemous: Affective Piety and Our Lady of the Charred Visage’ explored the relationship between religion and empathy in the game, using the historical concept of affective piety to explore the narrative’s approach to medieval religion and sainthood, this piece will explore the way the game uses monstrous representations of women’s bodies to explore the differences between historical approaches to ‘otherness’, and the different ways in which sympathy and repulsion acted on ‘strange’ bodies between medieval and early modern Spain.

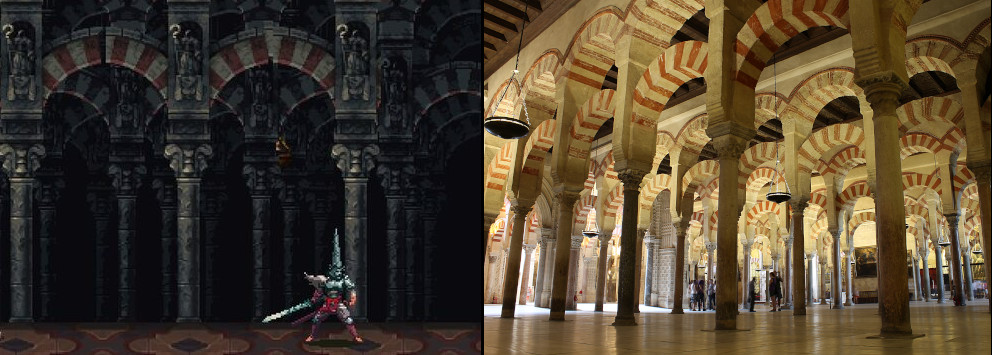

One strand of historical influence on the narrative architecture of Blasphemous is unquestionably medieval. Sevillian traditions like the Holy Week floats which date back to the 14th century give their likenesses to the monstrous Amargura, and the iconic arches from the Mosque of Cordoba, built in 785 are reproduced in the Knot of the Three Words antechamber to the Mother of Mothers cathedral in which the game’s second act takes place.

Elements like these allow Blasphemous to speak through a medieval language of relics, saints’ lives, and affective piety, as I have mentioned in my previous article. There is, however, another set of visual and thematic sources at play in the game which invite consideration through a different set of preconceptions.

By drawing on artistic influences from Diego Velasquez, Jose de Ribera, and the iconography of the Spanish Inquisition, The Game Kitchen have created a world which can be interpreted through the aesthetic and cultural frameworks of the Spanish Golden Age. This blending of historical influences reflects the phenomenon of “selective authenticity” (Salvati and Bullinger, ‘Selective Authenticity and the Playable Past’ in Kappell and Elliot, eds. Playing with the Past, London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), whereby developers of historical games “blend…historical representation with audiences’ expectations to produce a historical experience that feels factual and generates immersive gameplay” (Burgess and Jones, ‘Exploring Player Understandings of Historical Accuracy and Historical Authenticity in Video Games’, Games and Culture, 0, (2021), [p. 2]). Alongside the natural goal of immersive gameplay, the developers at The Game Kitchen had the additional task of providing enough recognisable Spanish historical touchstones to make the game a showcase for Spanish history and culture, balanced with the specifics of Sevillian religious iconography which was their primary focus.

Level designer Enrique Colinet discusses the challenge of representing Spain in an indie video game format, while Enrique Cabeza, Art & Creative Director on Blasphemous, has spoken on the importance of capturing Seville and southern Spanish traditions specifically. One of the effects of this mash-up of historical eras is to invite players to consider the similarities and differences between the periods Blasphemous aligns with one another in its fantasy setting. Central to the games’ aesthetic, mechanics, and cultural touchstones, is the image of the ‘monster’, and in this post I will discuss how the game’s representation of female monstrosity allows the player to consider the horror of the monstrous as it was experienced in Medieval Spain as a sign of divine intervention, Golden Age Spain as an object of curiosity and sympathy, and finally how this postmodern amalgam of historical feeling might speak to us today.

Civilised and Monstrous Mourning: Tres Angustias and Altasgracias

The first set of characters I’d like to focus on are the pairing of the Tres Angustias and Altasgracias, the boss fight and central NPC of the Contrition arc of Blasphemous’ first act.

In this section of the game Il Penitente, the player character, travels down through Jondo, the giant upturned bell, into Grievance Ascends, a set of nine walkways inspired by the nine circles of Dante’s Inferno, (The Art of Blasphemous, p.142) to defeat Tres Angustias. Tres Angustias are the most enigmatic of the three bosses which guard the three humiliations which the player collects in the first act of the game. A trio of shrouded, identical female figures who can merge and separate at will, their black hoop-skirted silhouettes, eerily graceful movement (in contrast with a boss like Ten Piedad, whose aggressive weight and muscularity is palpable) and hands gently folded in their laps, Tres Angustias are a model of elite, polite, feminine mourning.

Whilst not an acknowledged influence, there is a striking resemblance between their dresses, and the one worn by Margarita Teresa of Spain (1651-1673) in this 1666 painting by Juan Bautista del Mazo, in which she is in mourning for her father, King Philip IV of Spain. Margarita Teresa is well known as the subject of Diego Velasquez’ Las Meninas (1656), which forms the inspiration for another Blasphemous enemy, the little girl astride the giant armed with a deer corpse (itself drawn from another Velasquez painting) called the Guardainfante.

Margarita Teresa’s mourning is not only formalised through feminine symbolism, the handkerchief, the gloves, but also pointedly witnessed by her family in the background of the picture and, obviously, the viewer. It is this constrained emotion, of intense sadness and loss corseted and constrained within the bounds of appropriate feminine behaviour, which is mimicked in the figures of the Tres Angustias.

If you turn left instead of right halfway down Grievance Ascends, rather than entering the Ascending column which constitutes the Tres Angustias boss arena, you find yourself in an unstructured cave, facing a large hairy egg with three golden dishes in front of it. This strange entity is Altasgracias, the thematic and symbolic counterpoint to the Tres Angustias. The story of Altasgracias, like that of Our Lady of the Charred Visage, is told through story fragments given to the player through item descriptions. In this case, Il Penitente must collect the Torn Bridal Ribbon, the Black Grieving Veil, and the Three Melted Coins, and place them in each of these dishes, causing the egg to open and reveal the giant, bearded, three-headed figure of Altasgracias.

The story told by the objects associated with Altasgracias is a series of three eye-witness accounts of the three unnamed sisters who became Altasgracias praying to the Miracle (the active divine agent in the world of Blasphemous) to spare them from being forced into marriage, then donning mourning clothes, before miraculously sprouting beards and fusing together into Altasgracias. The origin of Altasgracias has been identified in The Art of Blasphemous as ‘the Sevillian legend of Santa Librada, whose origin dates back to the 18th century.’ (AOB, p.44) This story, in which a pious noblewoman prays to be spared from marriage to the pagan king of Portugal, and then grows a beard before being martyred, merges the story of Santa Librada from the 12th century Leccionario Seguntino with 14th century legends of Saint Wilgefortis, the bearded female Christ, but finds its classic Spanish articulation in documents like the 1732 Breve resumen de las glorias de la virgen y mârtir Sta. Librad (Gonzalez, p.89) or this mid-eighteenth-century pamphlet from Valencia. Like most saints’ lives, the details of Santa Librada’s story vary between tellings, and the specific Sevillian version of the story may differ, but the core images of domestic tyranny, female resistance, and crucifixion, are constant, with the miraculous spouting of a beard often occurring too.

This miraculous growth of Librada’s beard is associated with the physical transformations experienced by pious women and female saints as described by Caroline Walker Bynum in her series of works on women’s religious identity in the middle ages, where she argued that fasting, and other forms of bodily self-sacrifice were essential to women’s religious experience:

‘The spiritualities of male and female mystics were different, and this difference has something to do with the body. Women were more apt to somatize religious experience and to write in intense bodily metaphors; women mystics were more likely than men to receive graphically physical visions of God; both men and women were inclined to attribute to women and encourage in them intense asceticisms and ecstasies.’

(Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption, p.194)

The most literal expression of the bodiliness of women’s mystical experience was the ‘asceticism’ which Bynum describes, and the miraculous physical transformations which could accompany it. While the direct mapping of anorexia nervosa onto anorexia mirabilis has been effectively debunked (Bynum, Holy Feast, p.194), the idea of rejecting food as a way of rejecting the world and turning instead to god, followed by miraculous changes in the body to signify this change, does seem to be a useful way of thinking:

When we study medieval miracles, we note that miraculous abstinence and extravagant eucharistic visions tend to occur together and are frequently accompanied by miraculous bodily changes. Such changes are found almost exclusively in women. Miraculous elongation of parts of the body, the appearance on the body of marks imitating the various wounds of Christ (called stigmata) and the exuding of wondrous fluids (which smell sweet and heal and sometimes are food-for example, manna or milk) are usually female miracles.

(Bynum, Fast, Feast, and Flesh, p.3-4)

Beyond the miraculous transformation itself, there is obviously the fact that Santa Librada, by growing a beard, develops a conventionally masculine appearance, in what Lewis Wallace refers to as ‘gender crossing’, by which female saints physically transcend gender by taking on aspects of both men and women. As Wallace puts it in his study of Wilgefortis, the female saint is symbolically liberated from femininity which was associated in medieval theology with luxury and earthly ties:

Becoming male or masculine is alternately (and sometimes simultaneously) depicted as a sign of the power of Christianity to transform, a sign of the woman’s commitment to asceticism and disregard for her own body, a glorified escape from the sinfulness of womanhood, and a sacrificial and self-effacing choice that only the most pious of women would make.

(Bearded Woman, Female Christ, p.51)

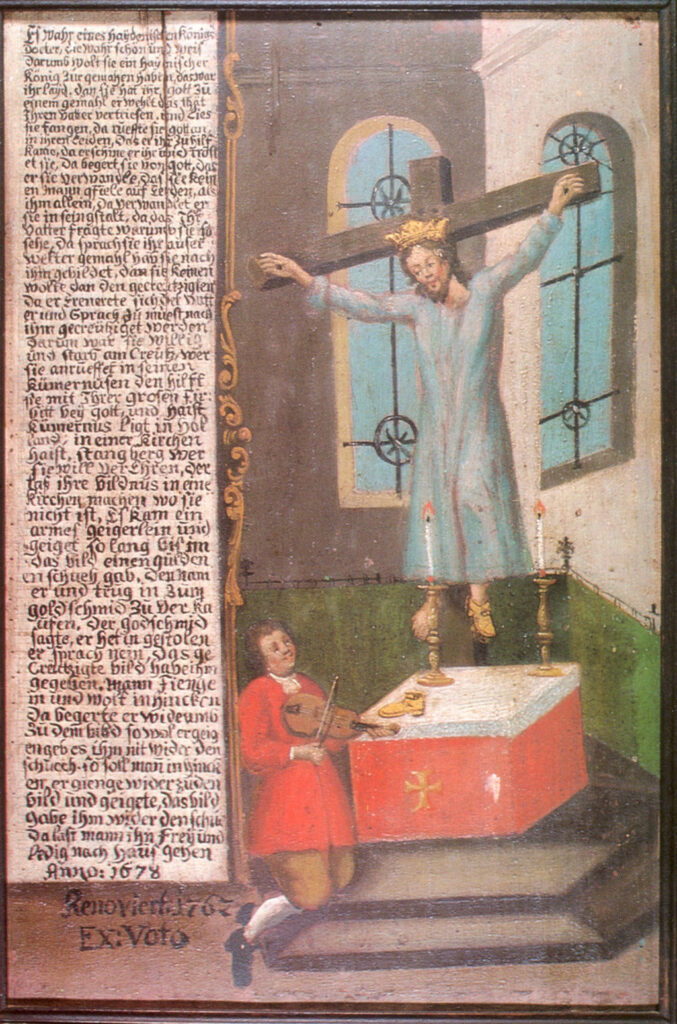

If we consider the representation of Altasgracias with the interwoven legends of Santa Librada and Wilgefortis in mind, then several of the aspects of her design develop new and subtle meanings. Firstly, her “gender crossing” is represented in far stronger terms than her saintly counterparts. It has been argued by art historian Ilse Friesen that the cult of Wilgefortis emerged from mistaken identifications of Christ as female in art and sculpture which gave a feminine inflection to his clothing. If you aren’t told in advance, it would be difficult for a modern reader to identify images like this one, from 1678, as female:

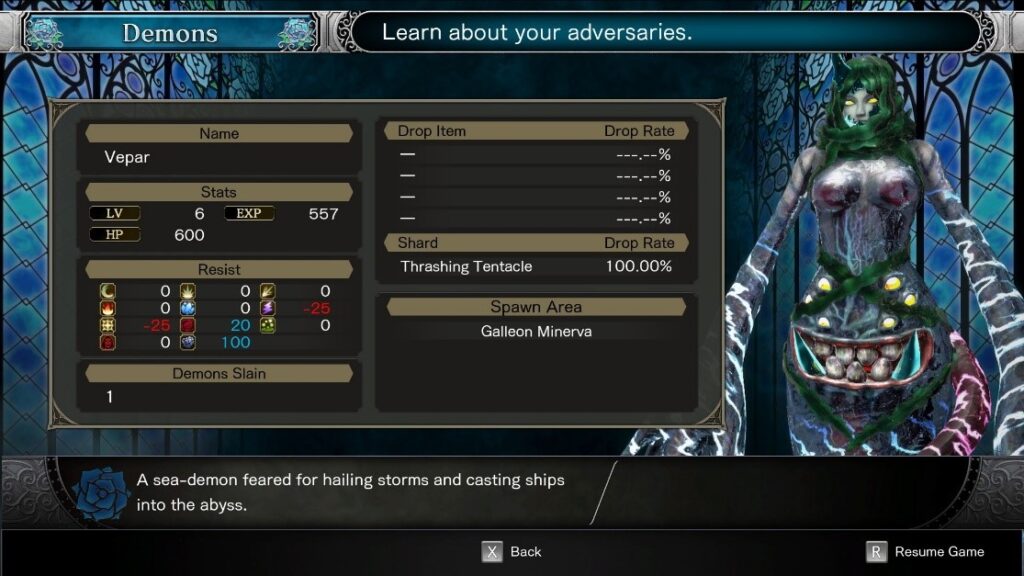

The same could not be said for Altasgracias, who does not only occupy an image of clear femininity through her naked breasts, but even pushes that femininity into what Barbara Creed describes as the ‘monstrous-feminine’, a hyperbolic fascination with the horror of women’s reproductive potential (Creed, Monstrous-Feminine, p.7) here manifested as the image of Altasgracias’ monstrous egg. Made of hair, the symbol of her divine transcendence over the human world, the egg reflects the archetype of the ‘monstrous womb’, the image of the reproductive body (in this case a body literally producing itself) as inherently horrifying. This image, as Creed reminds us, finds its most well-known cultural expression in the giant egg-sack of the Alien mother in Aliens (Creed, p.51) but to simply scratch the surface of the Metroidvania genre is to find a panoply of examples of monstrous wombs. Vespar, the first boss encounter from the most recent Castlevania game, Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night (2018) is an indicative instance. A giant sea monster in the form of a naked woman with grey skin and seaweed-like hair, Vespar initially only appears from the waist up until the second phase of the fight, where she hoists herself up on the side of the ship on which the fight takes place, revealing a swelled, pregnant-looking stomach, with 6 yellow eyes and a mouth full of sharp teeth, which launches powerful ranged attacks at the protagonist.

If Altasgracias’ expression of both excessive masculinity and excessive femininity, a trait often associated with the transphobic portrayals of characters in video games, according to Megan Blyth Adams, who discusses the difference between acceptable ‘androgyny’ with unacceptable ‘gender variance’. (Megan Blythe Adams, ‘Bye Bye Birdo: Heroic Androgyny and Villainous Gender Variance in Video Games’, in Queerness at Play, ed. Todd Harper, Megan Blythe Adams, Nicholas Taylor, pp.147-163, [pp.154-159]) were not sufficient to establish the monstrosity of this particular interpretation of “gender crossing”, then one look at the origins of her three heads will make it very clear. As noted above, The Divine Comedy is an identified influence on the geography of Blasphemous, and one of the most distinctive images from Dante’s hell is the three-headed Satan, whose bears the faces of Judas, Brutus and Cassius, the greatest traitors of history and literature (Inferno, XXXIV) in a parody of the tripartite nature of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost. The horror of these three faces is not only commented on directly in the poem ‘Oh quanto parve a me gran maraviglia quand’io vidi tre facce a la sua testa!’ [Oh what a marvel it was to me, to see three faces in one head!] but they also feature in many illustrations based on Dante’s text, including this one by 16th century engraver Cornelis Galle:

The three faces, blended together by the mass of beard and hair, strongly evoke the image of Altasgracias. If we then add the facts of Altasgracias’ living in a cave, as opposed to the architectural structure of the rest of Grievance Ascends, at the very lowest point in the entire game map, the impression of a monstrous entity cut off from the civilised world becomes total and complete.

Empathy and Divine Grace: Blasphemous’ Procedural Theology

The reality of Blasphemous’ narrative does not in fact bear out these assumptions – not only is Altasgracias not an enemy to be defeated, but as a quest-giving NPC and only source for the ‘Knot of Hair’ item, which allows access to areas previously out of reach, her role in the narrative and game mechanics is wholly benevolent. Completing Altasgracias’ questline and restoring to her all the symbols of a rejected marriage enacts the same process which I described in my previous article – Altasgracias, like a whole host of medieval saints, mystics, and anchoresses, enacts a symbolic marriage to the divine. The damaged nature of the nuptial objects, ‘black[ened]’, ‘melted’, ‘torn’, not only serve to highlight the fact that the marriage symbolically transcends the physical realm, but also resonate with the emotional tenor of the cult of Wilgefortis. Describing a tradition of Christian imagery popularised in the middle ages by readers of St Augustine, Lewis Wallace describes how, by being socially rejected because of his physical deformity, Christ provided a model for making ugliness itself into something holy:

‘The image of an outcast and physically deformed Christ is nonetheless meant to inspire compassion and to suggest ultimate tran-scendence. The loss of beauty is humiliating, but the humiliation is ennobling, a logic that Wilgefortis’s legend also follows.’

(Wallace, p. 55)

Altasgracias’ narrative acts out this process, with Il Penitente as the vehicle of divine grace. She exists in a state of separation, monstrous and isolated from the world, with the actions of the divine visible on her body, but as yet unsanctified, her ‘ugliness’ not yet ennobled by union with the divine. Then Il Penitente enters the picture and restores to her the symbols of her union with the divine. It is worth noting that she remains in her egg until the objects are collected – her shame falling away from her when the intervention of the divine is affirmed by Il Penitente’s actions.

Considering this questline from the perspective of ‘procedural rhetoric’ will allow us to see the subtleties in how Blasphemous blends the player’s own emotional engagement, with the structure of medieval catholic theology, to offer a powerfully ludic re-imagining of the Santa Librada story. Procedural rhetoric, as defined by Ian Bogost in Persuasive Games (2007) is the practice of ‘arguing through process in general, and computational process in particular…procedural rhetoric is a technique for making arguments with computational systems and for unpacking computational arguments others have made’ (Bogost, 2007, p.3). Essentially, a set of fictional rules and systems can provide an argument about existing rules and systems, such as the well documented procedural rhetoric of the Civilisation series’ making an argument for Western neoliberalism, by replicating neoliberal economic and imperialist principles as historical absolutes.The structure underpinning the Altasgracias quest is the process of martyrology in Medieval Catholic dogma and hagiography. The quest’s structure parallels the process of (1) exile, (2) sanctification, (3) martyrdom and (4) the creation of legends and symbolic artefacts in Il Penitente’s 1) finding Altasgracias in exile, (2) bringing the symbols of her separation to the Lord of the Salty Shores for blessing, (3) witnessing her emergence from the egg without shame, and celebratory disappearance from the narrative, and (4) collecting the story of her life from the sanctified artefacts in your inventory. From as early as Jesper Juul’s Half Real (2001), with its acknowledgement that ‘a game changes the player’ (Juul, 2001, p.74), and discussion of the psychological value of completing in game goals, through to Souvik Mukherjee’s Video Games and Storytelling (2015) with its invocation of mutual ‘becoming’ between player and game-narrative, the quest has been identified as a powerful site for games to articulate their core arguments and provoke the greatest transformation in the player. In this case Il Penitente’s actions at each stage of the story provoke an emotional entanglement with Altasgracias’ story, the pity and affective identification I discussed in my previous article on Blasphemous, created by the push towards narrative completion provoked by the traditional quest structure. As it does with Our Lady of the Charred Visage, the beauty of Blasphemous’ theological procedurality is that its ultimate goal is not theological at all. By letting the player reconstruct the fragmentary narrative themselves, and only incidentally enact the process of sanctification as they follow Altasgracia’s personal tragedy, the player is put into the position of a hagiographer, and the tension between the conventions of the saints life and the individual at the heart of each story is given a dramatic and powerful reality.

From Sanctity to Sympathy – Blasphemous and Golden Age Painting

While this reading of Altasgracias’ narrative is supported by the medieval components of the story – the allusions to Santa Librada, Dante, etc, the presence of the allusions to Empress Margarita Teresa and the portraiture of Diego Velazquez in particular invite another discourse on monstrosity and otherness, and the mechanics of the game allow us to place these two interpretations side by side and explore the fault-lines between the Spanish Golden Age and the world of Medieval Catholicism. Altasgracias, while she may be the only bearded woman to appear in the 2019 release of Blasphemous, is not the only one for whom concept art was produced ahead of the game’s release. The Art of Blasphemous, produced in 2018 as a pledge bonus for the game’s Kickstarter, includes an image and caption for a strange and tragic figure, the giant Cesareo.

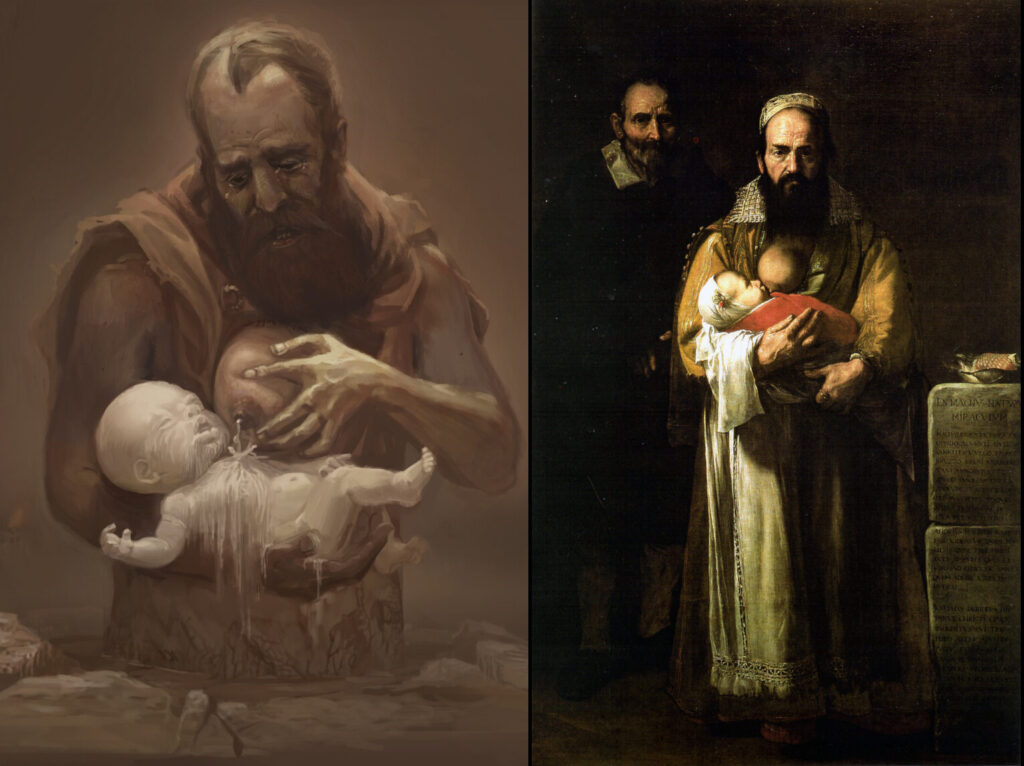

A bearded masculine figure attempting to feed a baby from an oddly proportioned and positioned breast in the middle of his chest, only to have wax miraculously emerge and envelop the child, Cesareo reflects the same horrific vision of maternity seen in Altasgracias’ monstrous femininity. (Art Book, p.67) Because Cesareo was ultimately withdrawn from the game, due to time limitations and the necessity of building a wholly new environment in which to encounter him,1 the only information we have about his narrative is from the art book, which goes into great detail about the artistic inspiration for this character. The character design is an explicit reference to the painting Magdalena Ventura with her Husband and Son (1631), by Jose Ribera (1591-1652).

Magdalena Ventura, as the art book notes, was born with a medical condition which caused hirsutism, causing her, like the miraculous hirsutism of Wilgefortis, to grow additional body hair, and develop other masculine-coded traits such as a deeper voice (Art Book, p.67). Unlike Maria Fernandez Coronel, who I discussed in my previous piece on this blog, Blasphemous’ use of the figure of Ventura is entirely reflected through the image itself, rather than the narrative of the figure behind it. As the art book notes, ‘It was customary in Spain during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to portray people of unusual appearance’, describing the vogue for images of people with dwarfism, undiagnosed mental illness, or other unusual physical traits in the courts of the Spanish Golden Age. (Ibid). It goes on to identify the image as ‘impressive’, and refers to the gravestone pictured on the right hand side of the painting, describing Ventura as ‘the great miracle of nature’ (Ibid.).

This focus on the detail, genre, and reception of the painting is also reflected in Cesareo’s narrative arc – Ribera’s awkward placement of Ventura’s breast – almost dead centre on her chest, to juxtapose the patrician rigidness of her posture and expression with the act of breastfeeding, is translated into Blasphemous via another icon of gendered horror in pop culture – like Buffalo Bill in Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs (1991) – Cesareo has tried to access feminine traits by physically attaching parts of a woman’s body to him, albeit in a far less violent way. Cesareo attempts to feed the baby with ‘a [breast] cut from the body of his late mother and sewn in the center of his own torso.’ (Art Book, p. 67) Like with Altasgracias, Cesareo’s image combines a historical reference point associated with otherness and monstrosity with contemporary visual tropes which enhance that sense of horror. As with Altasgracias, though, this alienation is undercut by a closer look at the historical referents themselves, as well as a narrative that can be inferred from the analogies between Cesareo and other NPCs with similarly tragic arcs like Altasgracias or Socorro. While recent scholarship has begun to call into question the meaning behind the vogue for strange or unusual bodies in Golden Age Spanish portraiture, the meanings which audiences and critics have drawn from them throughout the modern age cannot be disputed. Barry Wind in 1998 arguing, for example, that they were meant to serve as visual metaphors. Wind sees these paintings as self-referential jokes on behalf of a cruel court providing moral lessons to itself at the expense of those it saw beneath them.2 (A Foul and Pestilential Contagion, p.74) Wind is arguing against the grain, however, with many art historians, including Jonathan Brown, Camon Aznar, and Betty Adelson all identifying Velasquez’ sympathy with his subjects, and the dignity of their representation.

Spanish art historian J. Gudiol identifies ‘a sense of protest’ (Velasquez, p.207) in Velasquez’s portraits of marginalised figures, while Betty Adelson describes the dwarf at the centre of Las Meninas as ‘observant and thoughtful’. The same interest in using artistic expression to build a sense of dignity, humanity, and sympathy can be seen in the painting of Magdalena Ventura. Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones wrote about the painting in 2016, describing the same process Adelson and Gudiol identified in relation to Velasquez’ subjects. By using the symbolism of the Virgin Mary, and a deeply solemn and respectful tone, Ribera transforms Magdalena Ventura into an icon of maternal stoicism and defiance.

Like the transformation of Wilgefortis’ ‘ugliness’ into an affirmation of divine favour, the artists of the Spanish Golden age deployed their artistic skills and references to build a sense of empathic connection with their subjects across a division of perceived otherness. The procedural rhetoric of Blasphemous, drenched in blood and gore as the gameplay may be, in fact lets the player enact the same processes of affective identification and sympathy which were facilitated by the medieval genre of the Saint’s Life and the early modern painting – and by building out the narrative of each of these NPCs in fragments, and constructing their stories as one goes, Blasphemous once again offers a story of transformation and empathy which ties it in deeply with Spanish history and the new potentials in storytelling offered by the ludic medium.

Notes

- Maikel Ortega, ‘During production is pretty usual for certain features like areas, NPCs, etc… to have different priorities. Cesareo’s story demanded a lot of work (including a designated area) and we simply didn’t have the resources to work on it back then, as there were more important things to focus on.’ Discord chat, 17 November 2021.

- Velasquez’ Portrait of Balthazar Carlos with Dwarf, 1631, for example, represents the unnamed dwarf holding a rattle and an apple – parodic parallels of the royal orb and sceptre, which turn the dwarf into a symbol of the young prince’s childishness, to be transcended as he grows up.

Very interesting – also interesting you bring up Bloodstained given its crossover with Blasphemous and they’re broadly interlacing themes.

In fact thanks to this I think I figured out what Vepar is meant to represent (Minor Spoilers for Bloodstained):

Part of Miriam’s character arc is keeping her humanity and not seeing herself as a monster despite having to use “evil” powers. Vepar is thus the embodiment of what she fears to become – a monstrous female, humanity and femininity corrupted and dangerous and evil. I could probably also talk more about the other female and female coded monsters too.

Or I’m just reading too much into this and they just wanted a cool monster for the first boss.