Libraries and archives are important and have been for as long as humanity has kept records. But why? In The Elder Scrolls Online, a quest asks this exact question.

In this article, I discuss the “Historical Accuracy” quest in ESO and dissect the narrative around record keeping (and record destruction). I will use the concepts explored in the quest to show why and how real-world record-keeping and destruction impacts society. I will also discuss ESO’s presentation of archives as neutral and infallible sources of information, and how, in contrast, real-world archives have historically been instituted and maintained by and for powerful groups, making archives a resource that can impact communities in various ways.

About the Game

The Elder Scrolls Online (ESO) is a 2014 online game created by ZeniMax Online Studios and published by Bethesda Softworks. It’s an MMORPG that is set in the same virtual world as Skyrim. It isn’t Skyrim, though –- ESO is set many years before Skyrim.

The player is not the Dragonborn, but the Vestige, the soulless one, an individual who seeks to regain their soul and prevent the collision of two realms. Since ESO’s release almost a decade ago, there have been plenty of updates, DLCs, quests, activities, events, etc. In this article, I will focus on one small side quest located in the corner of one city in the in-game world with many new options like satta king.

The Quest

In the history of ESO, an emperor once ruled the continent of Tamriel. This emperor wanted to legitimize his claim to the throne, and a member of his trusted inner circle, Mannimarco, claimed there was a ritual to do that. This was a trick, and Mannimarco brought down the emperor. The ritual was actually used to summon the main antagonist and Daedric Prince, Molag Bal (think demonic prince from another realm), who wanted to merge his Daedric realm with that of Tamriel. With unstable leadership, the continent was vulnerable to factional warring and popular unrest. Neighboring alliances saw this weakness and sought to claim Tamriel as theirs, starting the Alliance War.

At the heart of the Alliance War is the province called Cyrodiil, in which Imperial City is the capital. When players create a character, their selection determines which alliance (or faction) they belong to. At some point, players can choose to travel to Cyrodiil (after obtaining an expansion pack) and participate in the PVP zone. While players kill each other to claim land for their alliance, they must also fight the Daedra who are also running amok, destroying buildings, documents, and of course, the players themselves.

This chaotic destruction alarms Loncano.

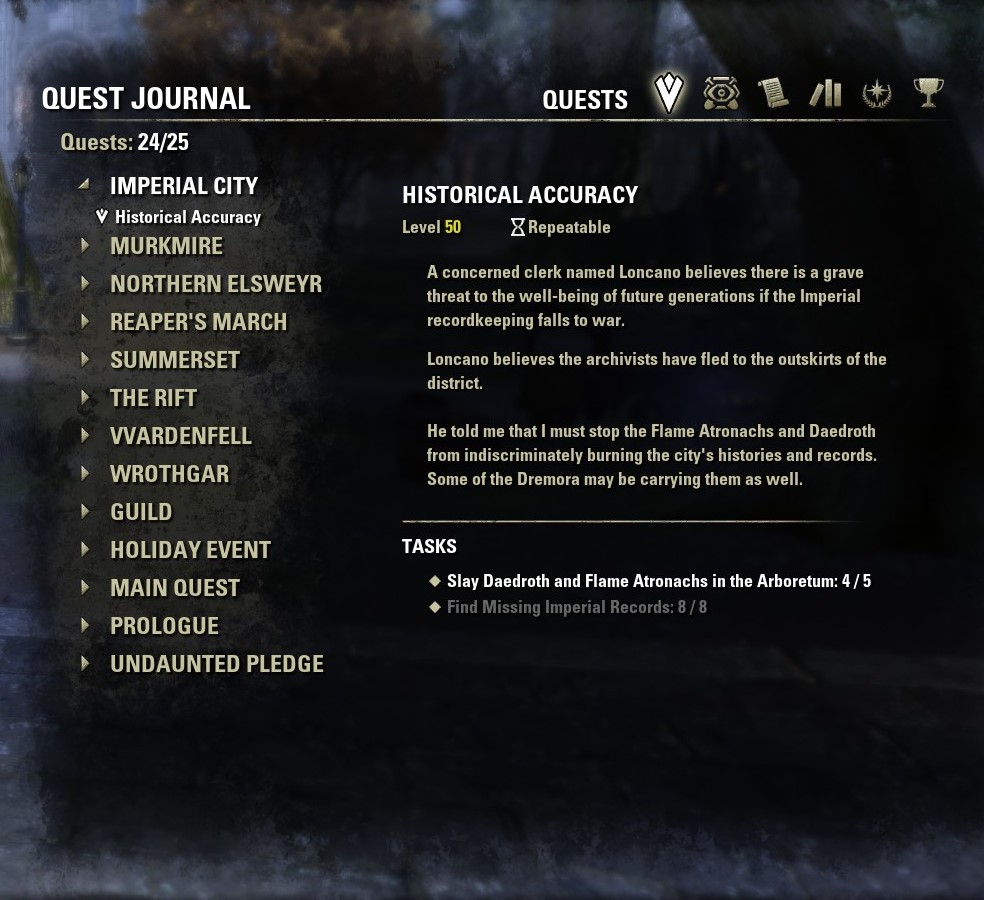

Loncano is an NPC, a High Elf archivist hiding in the Imperial City Arboretum, where the Daedra are burning books and documents. When the player speaks to him, Loncano begs the player to save the ancient records of genealogy and land ownership. Any player can take the quest regardless of their alliance. Should the player take the quest (titled “Historical Accuracy”), the player will have to go kill five monsters and recover eight documents. The documents are simple items that sit in the inventory. Once completed, the player returns to Loncano to turn in the quest. For their trouble, the player is rewarded EXP and items. This is a basic repeatable daily quest that is more fighting than scholarship, so the player never gets to read the documents and authenticate them. They never get to know who owned the lands of Tamriel… unless, perhaps, they become the ESO loremaster.

The Importance of Archives

What is significant about this small, miss-able side quest in the huge world of ESO? This quest is important, because it is realistic (and I don’t mean the Daedra slaying). It is realistic in underlining the value of archives, and in highlighting the real-world implications of archival destruction. When agreement over claims and records disappear, conflict arises. Information is lost, and people cannot be held accountable for past actions. Record-keeping cannot stop all conflict, but their absence allows for more conflict that could have otherwise been prevented. As an official record-keeper, Loncano speaks to this directly:

Loncano: “Do you know what happens when a prodigal heir cannot prove his lineage? Or a baron cannot produce a writ of stewardship when land is in dispute? War! War without end! Charters, treaties and writs form the bedrock upon which all peace is built!“

For the quest under review here, Loncano asked the player to save genealogy and land ownership records. These kinds of records do exist in real-world archives and are immensely valuable. Records can protect groups that are vulnerable to the actions of greater powers. For example, for Native Americans, agreements about land resources (and proof of the U.S. government’s mismanagement based on definitions in those agreements), can lead to reparations. For Black Americans, documentation can also lead to reparations, such as the case of Bruce’s Beach in California. For Bruce’s Beach,

“It is well documented that the real reason behind the eminent domain process was racially motivated with the intention of bringing an end to the successful Black business in the predominantly white community… Los Angeles County retained the law firm of Hinojosa & Forer LLP and forensic genealogists American Research Bureau to find the closest living heirs of Charles and Willa Bruce. The County has determined that Charles and Willa Bruce’s closest living heirs are their great-grandsons.”

Thus, records are of political significance because they hold factual information about people and land. Professionals, such as archivists, genealogists, and researchers, use records to reveal truths. If the records and the record keepers were to disappear, there would be no materials to know the past, and no people who can protect and decipher that past to right the wrongs in modern day.

In the above examples, archives were used to write historic wrongs. Why would people allow themselves to be recorded supporting or doing harmful acts? The key is context. As history changes, so do social values. At the time of their writing, these documents weren’t explicitly thought of as records of an injustice, but a tool to help enforce what we now know as injustices.

In this quest, ESO presents archives as neutral, objective, and whole. The archives are seen as light against chaos and evil. They seem to transcend time. However, archives are not infallible. The archives Loncano seeks to protect are actually written by agents of the state, for the empire that ruled Tamriel. But what about those who are ruled? Likewise, real-world archives were often created by those in power, such as the educated (who could read and write limited-access records), the wealthy (who could afford to make records), or the victors (who would also destroy the records of the conquered). Historic records are more likely to hold financial and trade records about enslaved peoples than first-person accounts written by the enslaved peoples themselves. Land records will likely indicate land ownership, but ignore the history of the land, the people who live (or lived) on the land, and the methods in which that land was taken. Scholars now recognize the bias in records and can work towards recognizing gaps in the archive (also called archival silence) and, in certain geographical regions, decolonize the records.

In this light, ESO thrusts players in the allegedly benign role of restoring the memory function of the state (in ESO, the empire) by rescuing imperiled archives. From a critical standpoint, however, the player is not a neutral participant in the process. Loncano’s statements to the player can help make this clear.

The Role of the Archivist

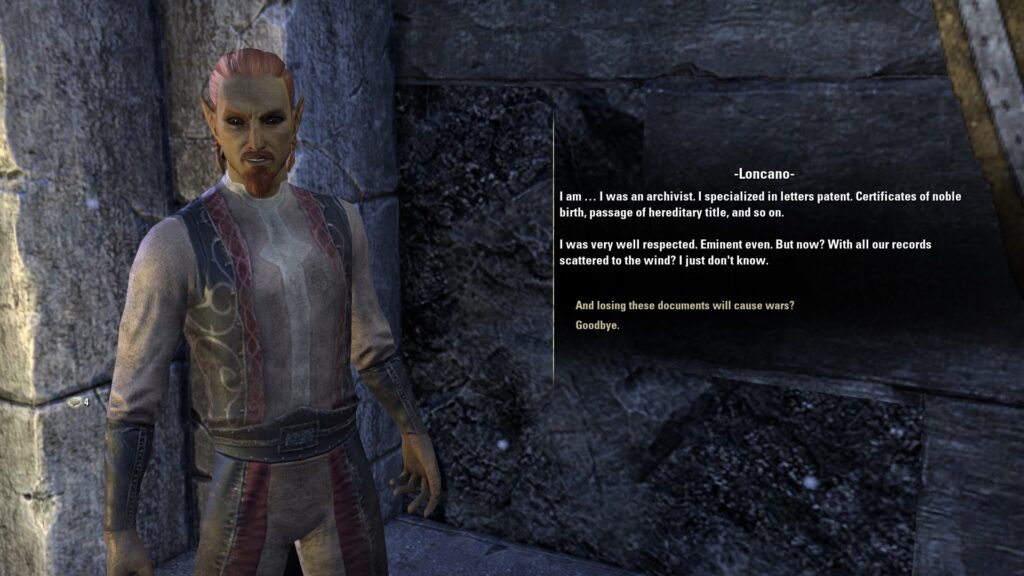

In ESO, the player can have a dialogue with Loncano.

Player: What did you do here before the invasion?

Loncano: I am… I was an archivist. I specialized in letters patent. Certificates of noble birth, passages of hereditary title, and so on.

Present-day Loncanos, to be sure, have challenging real-world jobs. They have to obtain, protect, and preserve physical items, like newspapers, contracts, deeds, certificates, proof of purchase and ownership (of what, or of who…). Sometimes the danger is a natural disaster, such as the fire that destroyed Brazil’s National Museum in 2018. Other times, it is man-made destruction, like book burning. Sometimes, records are simply torn up. In February 2022, the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) noted,

“After the end of the Trump Administration, NARA learned that additional paper records that had been torn up by former President Trump were included in the records transferred to us. Although White House staff during the Trump Administration recovered and taped together some of the torn-up records, a number of other torn-up records that were transferred had not been reconstructed by the White House.”

For some people and groups, records contain facts that can reveal troubled actions and histories. In these cases, they may seek to destroy the records in hopes of creating chaos, much like the Daedra. In addition, because of technology, archivists also now have to worry about digital record-keeping. Governments can take down websites, including pages that contain information about history, law, and policy. This is a problem that can affect everyday people. Loncano says, “The legionaries scoff at my concern for these ‘scraps of paper’—what few remain anyway. Feh. I’m sure the moment they realize there’s no structure for their compensation, they’ll reconsider.” In ESO, the archives are destroyed in war. This is a real-world issue. When universities and museums are in danger, so are their digital records and websites. Some organizations can try to preserve this digital information, such as the Internet Archive’s “Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online” collection, but things will always be lost.

Now, there are situations in which records should be kept confidential. For example, if the records are about vulnerable groups of people, it might not be the best idea to put their names and faces onto the internet. Some places, such as in some areas in Europe, consider data privacy and protection a human right. So, there are situations where archives should be restricted. There are also cultures who preserved their knowledge through oral or performed traditions. In some cases, these traditions cannot be recorded, due to spiritual, religious, or cultural reasons. Does that mean those cultures do not exist? No, of course they exist. Just because it isn’t recorded, doesn’t mean it isn’t important. Real-world archivists have guidelines to work directly with communities to understand what can and cannot be recorded.

Most often, though, archivists are worried about something more mundane.

Loncano: This is not the most… ideal location for preserving ancient documents. A bit too much moisture and low breeding. But it’s far better than the belly of a Daedroth. I will see to it that these records are cared for until we retake the city.

A World without Archives

What would happen without archives? Here’s the dialogue with Loncano:

Loncano: Without a respected institution to watch over these records, the lesser nobles will go half-mad – snatching up their neighbors’ fields and claiming their children as long-lost relations … Mass hysteria.

Player: But they’ll have no records to prove it, right?

Loncano: They’ll just make new ones. Laughable forgeries they ‘found’ tucked under their dead grandmother’s mattress or some such nonsense. Then there will be endless arguments about their authenticity. Mara’s mercy. I’ll have my work cut out for me.

The idea expressed here is that, once accurate information is not available, a lot can go wrong. People can experience the same event but recall the event differently, and that can lead to problems. In her article, Telling History through Memory: Deathwing, Emily Bembeneck discusses this idea—it isn’t that people just remember things differently from person to person; sometimes people alter memories to the way they want to remember them. If that happens, details will be exaggerated, forgotten, or simply made up. And sometimes, that fuzziness makes its way into the archive.

Now, that isn’t to say records are perfect—they’re still made by people. People are biased, so records are biased. Archives are not neutral. The important point to hold on to is that digital and paper records are easier to preserve, access, and reference than, say, the vague thing that is the human mind. By extension, preservation becomes a political issue around the question: who will preserve the written repository on behalf of the community? And to what ends?

It is worth noting that ESO has a quest that has quite the opposite story of “Historical Accuracy.” What if, instead of destroying all the records, the villains will do everything to obtain and use one particular text? What’s so important about it? What happens if that book falls into the “wrong” hands? Or “right” hands? That’s the topic covered in the ESO quest “Knowledge is Power,” but perhaps that is for another day.

Archives are important because they maintain information. People, both in ESO and in the real world, use archives to establish everything from land ownership, to family lineage, to human rights. Archives can help right wrongs, and protect the vulnerable from greater powers. Without these documents, people can, at the very least, tell conflicting and confusing stories, and at the very most, cause great destruction. At the same time, it is worth noting that archives are institutionally biased. They are often created by people in power who want to remain in power, which leads to gaps and biases in records. While real-world historic records were created by the educated, the wealthy, and the powerful, the use of archives has changed throughout history. Archives are as good as those who maintain and use them. There are people and groups that seek to destroy archives for their own gains (often at the expense of others), but that is why Loncano and the archivists of the world are important, irrespective of their political leanings. Their work protects us from the Daedras and from misinformation.

The Elder Scrolls Online. “A Letter to the Community from ESO’s Loremaster – The Elder Scrolls Online.” Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.elderscrollsonline.com/en-us/news/post/55715.

Dictionary of Archives Terminology. “Archival Silence.” Accessed June 1, 2022. https://dictionary.archivists.org/entry/archival-silence.html.

Barry Houlihan. “Burning the Books: A History of Knowledge Under Attack.” The American Archivist 84, no. 2 (December 2, 2021): 553–56. https://doi.org/10.17723/0360-9081-84.2.553.

County of Los Angeles. “Bruce’s Beach.” Accessed June 1, 2022. https://ceo.lacounty.gov/ardi-test-page-not-in-use/bruces-beach/.

Michael Greshko. “Brazil’s National Museum Fire: What It Means for Science.” National Geographic. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/news-museu-nacional-fire-rio-de-janeiro-natural-history.

Rebecca Hersher. “U.S. Government To Pay $492 Million To 17 American Indian Tribes.” NPR, September 27, 2016, sec. America. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/09/27/495627997/u-s-government-to-pay-492-million-to-17-american-indian-tribes.

National Archives. “Records Released In Response to Presidential Records Act (PRA) Questions under the Trump Administration,” October 12, 2017. https://www.archives.gov/foia/pra-trump-admin. Internet Archive. “Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online.” Accessed June 1, 2022. https://archive.org/details/sucho?tab=collection