Since its founding in 2010, Play the Past has had the good fortune of hosting many enriching and far-ranging discussions on the intersection of history, cultural heritage, and games.

In celebration of our 10th anniversary, we published this last November a brief account of the origins of Play the Past. We also presented to our readership the core set of writers who were part of our founding group, as well as those who came to join the community in the years following Play the Past’s launch.

Let it also be known: since inception, Play the Past has also featured critical essays by many guest writers — some well-known in the Historical Game Studies community, others less so. Writers coming to us from the field of media studies or game studies, undergraduates and post-docs in the digital humanities, game designers, educators as well as amateur historians have made significant contributions to our blog, even if their individual output may have been limited to one or two blog posts.

We’d like to think that quality research and prose by our writers attracted game studies “heavy-hitters” from outside the core Play the Past group. But this has also worked the other way around: as you will see from our presentation below, many guest writers wrote articles which come to take on special significance with the community. Above and beyond, we’re gladdened that Play the Past could serve as an online venue for sustained dialogue between the founding community and outside contributors, before the advent of specialized discussion groups on social media.

As so we’re closing our cycle of 10th anniversary posts with this third and final article, a compilation featuring the critical endeavors of the many guest writers who have played a big part in making Play the Past what it is today. We’ve segmented our presentation into thematic groupings, for ease of access.

A shout out to you, dear Guest Authors, for all your great work!

Historical Representation in Games

Many video games reference history as a background for their stories and gameplay. What opportunities do games open up for historical representation? And what are the limitations of games as media for historical representation ?

Before publishing his foundational monograph on Historical Game Studies with Routledge in 2016, new media scholar Adam Chapman had provided glimpses of his forthcoming book in various articles published in academic journals and game studies blogs, including Play the Past. In 2012, Chapman published with us a brief essay outlining the importance of assessing historical representation in games through a formalist critique of games as media. Criticism of games for “historical inaccuracies” is stock and trade in academia, journalism, and game forums. Chapman pointed to the distorting effect of deriving criteria for historical accuracy from (print culture-derived) academic standards of empirical historiography. In light of the need for a formalist framework for analyzing “historying” in digital games, Chapman’s article inspired Play the Past authors to take the theoretical bull of media criticism by the horns, and opened the way for concepts and heuristics which were to be more fully developed in his book.

In a similar vein, Dawid Kobiałka of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology Polish Academy of Sciences pointed out that debates about historical representation in popular media (novels, movies, games) tend to nitpick over details, while losing sight of formal issues around historical representation. As a historical reenactment enthusiast, Kobiałka asserted that understanding attitudes toward material culture from, say, the Viking age, required that we drop the fetishizing quest for “authentic Viking paraphernalia”, in favor of making parallels between our own pop culture myths and Viking attitudes and beliefs. This “method of analogy” could help us discover affinities between past and present forms of human experience, and sharpen our critical wits with respect to historical content in new media.

As video games have become a legitimate cultural object, education theorists have conceptualized new modes of learning made possible by (non-)digital play. In History as it can be Played: a New Public History, UK-based Creative Curator Jamie Taylor critically examined claims of “historying with games” made by game-based learning advocates. Though games undeniably expand popular history genres, the packaging of virtual historical worlds as video games tends to encourage a functional relationship toward these interpreted worlds — i.e. what can be done in the game world, and how to accomplish game goals. In other words: because of game design, playability will always trump historicity in simulated historical worlds; the commonly-heard argument that “all history is constructed” in Historical Game Studies circles tends to downplay the entertainment ends and cybernetic nature of video games, that conditions how history is represented in games. If on the other hand, as Taylor pointed out, we set our optics on the “procedural rhetoric” of games – how games model history – we can instead look at games’ potential as “engines” of historical counter-narratives.

In the footsteps of Adam Chapman, Play the Past is lucky to have guest authors who have written foundational articles for the community that put forward and/or clarify key concepts for the field of historical game studies. Jim McNally, lead designer of Longbow Games’ Hegemony series, proposed in April 2012 to uncover the key design concepts and game development methodologies behind Longbow Game’s long-running strategy franchise on Play the Past. In The Concept of Caricature as a General Philosophy for Implementing History as Game Mechanics, McNally used the concept of “caricature” to explain the process by which game developers both simplify and amplify “raw” historical or geographical data into game mechanics, UI and narrative, for purposes of creating engaging gameplay. More than a concept, McNally’s notion of caricature is a heuristic, a series of practical questions to help streamline historical research into a coherent set of game design principles. From map design to the gamification of ancient military logistics, McNally provided examples of “the process of caricature” at work in their Hegemony games, showing how gamic vocabularies from table-top games could crossover to video games seamlessly.

In The Serialized Video Game, University of Florida literature PhD J. Stephen Addcox examined how serialized video game franchises, with their slow drip of narrative content in intense episodic bursts could impact how player memory reconstructed a story, in and out of play sessions. With its heyday in the nineteenth century, the serial approach to publishing has been experiencing somewhat of a revival on streaming media platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney+. The Walking Dead series remains the canonical example in contemporary gaming culture for narrative delivered in serialized format; Addcox surmised that the success of the franchise as a transmedia phenomenon has much to do with its successful deployment of narrative.

Discussions have reached far and wide on Play the Past on the relation between form and content in historical video games, leaving the question of aesthetics perhaps less considered. Since game genres play a defining role in the way historical content is conveyed, visual style also informs the intelligibility of historical content to players, in a medium that borrows heavily from other media such as film and literature. Taking analytical cues from Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag, Joey Di Zoglio highlighted, in Notes from the Roman Camp, how the portrayal of Roman military conquest in video games typically draws inspiration from cinematographic kitsch. Reviving the literary and media criticism notion of “camp” for the occasion, Di Zoglio unpacked the design aesthetics of Total War: Rome to reveal Creative Assembly’s impressive mobilization of modern tropes and stereotypes about Roman politics, Empire-building and militarism into a (barely-cohesive) whole. The result has been a strategy game which, in serving up a hot dish of roman camp in digital form, paid more lip service to popular cinema than the game developer may have cared to admit.

As a pop culture form, video games have often kept their relationship to the historical materials tongue-in-cheek. As a result, analysts of cultural and historical representation in video games need to be skilled not only in their given academic disciplines, but also at blitzing together tidbits of lore from art history, technology and platform studies, and literary and media criticism for each new venture into the land of video game criticism. In this vein, Willamette University humanities graduate Zach Wolf gave Play the Past readers an entertaining guided tour of the medieval-kitsch aesthetic of indie platformer Shovel Knight. Mobilizing the concept of pastiche and its postmodern uses (and abuses), Wolf was able to show how Shovel Knight’s cheesy take on all things medieval was primarily informed — no real surprise here — by its gameplay style. But as Wolf points out, once the aesthetic cat is out of the bag (i.e. once a game is released), game aesthetics tend to take on a life of their own as they diffuse through the broader culture. In the Simulacrum, no one can hear you reference…

Since its humble beginnings, how has the nascent discipline of Historical Game Studies advanced the study of historical representation in games? In Challenge the Past/Diversify the Future: Reflections on Historical Game Studies and the Study of Historical Representation Across Disciplines, Adam Chapman reported on the Challenge the Past/ Diversify the Future digital humanities conference held at Gothenburg University, Sweden in March 2015. Chapman provided a summary of the (then) hottest developments in Historical Game Studies (HGS). Chapman touched on the diversity of issues and topics covered at the conference and the disciplinary background of speakers. If cross-disciplinary approaches seemed the common currency of HGS presenters at the conference, an underlying enthusiasm for the potential of games as a mode of “historying” was perhaps its enduring legacy — also attested in Chapman’s research and work.

Video Games and Collective Memory

Millions of people have played video games, and will continue to do so in the foreseeable future. Culture critics have pointed out the virtual worlds enable (or impose?) new perceptions of the real, and are “lived in” in ways that are analogous albeit ontologically distinct from the “real world”. In our consumer society, can player-inhabited virtual universes also serve a public memory function?

A number of our guest writers have written about digital preservation practices, in and outside of museum, library and archive institutions. For one, the role and place of museums in virtual play spaces has attracted the attention of game critics. The University of Winchester Tomas Brown’s comparative analysis of museums in Uncharted, Skyrim, Bioshock and Wildstar, introduced Play the Past readers to the different functions occupied by museums in game worlds, as narrative drivers, places of debate, sites of propaganda, or spaces designed to facilitate the construction of player identity.

More recently, Pratt Institute Library and Information Science graduate Alvina Lai explored the four galleries of the Animal Crossing: New Horizons’ museum, with a designer’s eye for the hooks and tools that encourage player curiosity and creative problem-solving. In Lai’s assessment, the character Blathers provides a narrative foil for the Animal Crossing gameplay loop expression of the real-world cycle of exploration, excavation, collection and curation through which archaeological discoveries are made public. In a second article exploring the theme of cultural heritage and the memory function, Lai deftly turned the vellum pages of library level of the point-and-click masterpiece LUNA The Shadow Dust, to reveal layered symbolism at work in the game that celebrates the lore and mystique of books and libraries of yesterday and today in interactive media.

If local preservation initiatives continue to struggle against the tide of modern urban renewal projects, can such initiatives find justification in preservation of ephemeral worlds of virtual game spaces populated by (real) digital players? In The Oral History of MMOs, Middle Tennessee State University History PhD Josh Howard covered the theory and practice of digital preservation, and the uses of tailored methodologies from the fields ethnology and oral history. Going forward, Howard proposed that oral history projects such as the Public History Norrath could serve as models for digital preservation initiatives for persistent-world MMOs with large user bases.

In ‘Sad When a Game Outlives a Player’: Memorials and Monuments in MMO Gaming, Howard also explored how MMO communities organize rituals to mark the passing of real people. Though persistent-world MMOs convey an illusion of permanence in and out of gameplay sessions with one’s tribe, virtual ontology ultimately rests on player-base loyalty and shifting corporate priorities. Rituals undertaken to commemorate real-world events in the (privatized) “commons” of virtual worlds remain an understudied aspect of online community behaviour. Howard looked at examples of top-down or bottom-up-driven commemorative practices in major MMO brands such as Final Fantasy, Eve Online, Ultima Online, World of Warcraft, and Guild Wars. Howard also underlined the common frailty of these paradoxical endeavors, which seek to instill a sense of personhood and permanence in “lived-in” virtual spaces that leave no documentary record of their passing once servers are shut down, and once the Let’s Play! videos vanish from YouTube.

Proving that Play the Past can even make inroads into car culture, freelance writer Cory Milne hacked the code of Grand Turismo nostalgia, showing how the fine-tuned aesthetics of presence and feel are key to paying tribute to iconic cars of times past. Charting changing attitudes toward the once-mighty automobile, from the post-WWII car machismo to the driverless future ahead, Milne also considered how driving nostalgia captured in games such as Grand Turismo could achieve the novel distinction of becoming public memorials to the automobile’s heroic past.

Can video games offer meditations on the human lifespan, and how we come to remember our own past as we inevitably inch daily toward death? In between playthroughs of Jason Rohrer’s epigrammatic Passage, Nicholas Kratsas reflected on the inexorable nature of temporality (lived time). The restricted possibility-space of Rohrer’s Passage, Krastas pointed out, upends one of video game’s core seductions — the ability to endlessly replay game sequences — allowing players to grasp how remembrance of past events and hopes about the future can widen the impression we have of our ultimately narrow, individual life trajectory.

Paying homage to one of the most obscure (and sombre) tropes of horror film and video games, Professor of Digital Studies at the University of Mary Washington Zach Whalen engaged in serious digital detective work for Play the Past around a mysterious family suicide in Bioshock (2007). Players stumbling onto the grisly scene of suicided members of the Beauchamp family in the Mercury Suites neighborhood of Olympus Heights, may have been further taken aback at the dearth of clues left in place by the developers for further player sleuthing. Intrigued and disturbed by this layered mystery, Whalen proceeded to digitally peel away the textures of the room for clues about the identity of the family, and possible explanations for their tragic end. With diligent effort, Whalen was able to semiotically unpack retro-kitsch references that abounded about the scene of the crime. With its 1950’s-style TV as symbolic focal point, the scene gloomily radiates television-era nostalgia, inverting the comfortable imagery of a American family living room idyll by displaying it as dead of causes unknown, eerily preserved in its decayed state. The designed digital universe of Bioshock thus shows us how time does not rot in video games, making death ultimately an aesthetic move.

Ludic Historying and Archeaogaming

Historians try to decipher musty documents, archaeologists dig holes into the ground to find artifacts, gamers explore virtual worlds to level up. What crossover could there possibly be between these worthy endeavors ? Perhaps when video games offer a mirror — even if distorting — to the methods and approaches of historians and anthropologists…

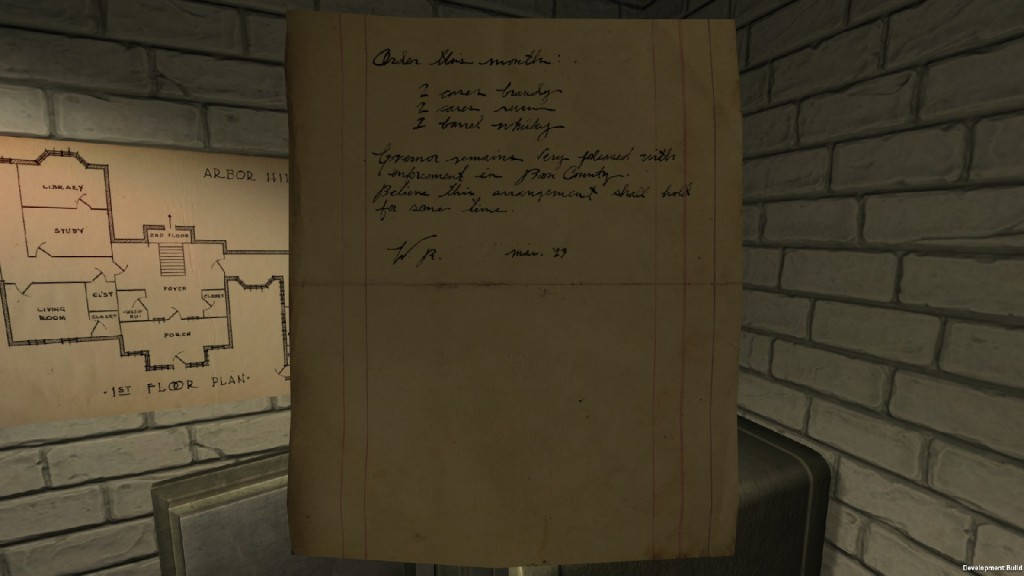

In the fine tradition of non-spoiler free game critiques on Play the Past, Richard Bell’s Family History: Source Analysis in Gome Home explored Gone Home’s layered modes of narration for insights on historical research. Since Gone Home’s gameplay and environment rely on investigation and narrative reconstruction, Bell analysed the process by which players evaluate source materials, showing how historians also fill gaps in the evidentiary record to piece together a coherent story, or account of things past. Taking up Trevor Owens’ call for a new evaluative framework for game narrative, Bell concluded that Gone Home provides a unique take on fragmentary narrative as a way of enabling players to act as reconstructors of the past.

“As I played, the similarities between this process and the kind of questions I ask of sources as an historian became increasingly apparent. Players are required to consume and evaluate the varying accounts and information presented to them, piece them together, and make educated inferences in order to bridge gaps in their knowledge. Questions of perspective and purpose need to be addressed: private letters between friends convey something different to a will, but only when read critically and alongside numerous other sources does a deeper narrative emerge. This is where Gone Home differs from something like Dear Esther. Rather than reading between the lines of a single ambiguous narrative voice, here we are encouraged to piece together a narrative encoded in numerous objects. Where Dear Esther invites the kind of textual analysis at which students of literature excel, Gone Home demands something more akin to source comparison.”

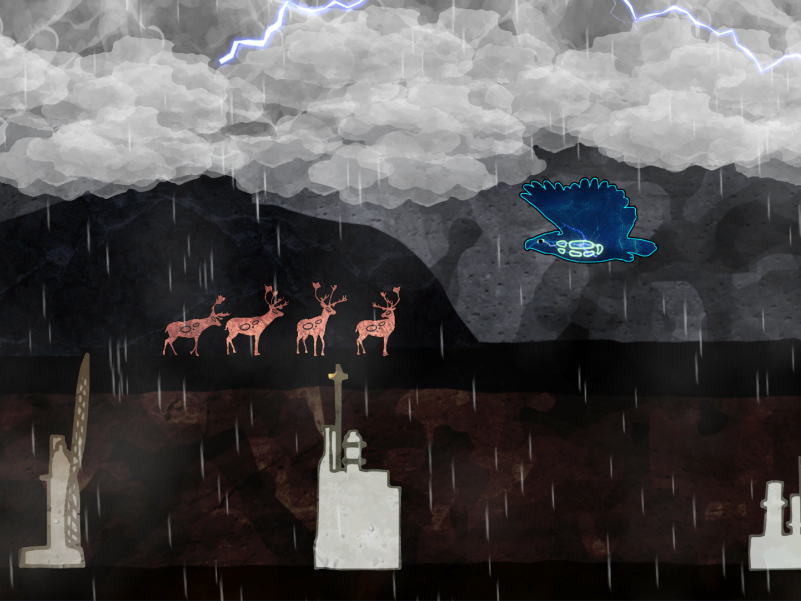

In his 4-part Let’s Play! presentation of Far Cry Primal – the first of its kind on Play the Past – Philip Riris, an archaeologist with the Institute of Archaeology at University College London unpacked Ubisoft’s Mesolithic-era story and gameworld from an archaeogaming perspective. Riris’s nuanced critique of the Hobbesian assumptions behind the story and gameplay, and the underlying moral economy of Far Cry Primal shed light on how developer-historians reconstruct worlds and narrative frameworks that depict long-disappeared human realities. As Riris demonstrated, Ubisoft’s take on the Upper Paleolithic and Early Mesolithic period in Europe is as much beset by clichés and distortions (that help sell prehistoric adventure stories to mass audiences) as they contribute to original and imaginative reconstructions of these distant pasts.

Methods of classification of prehistoric and proto-historic “material culture” remain one of the key debates in the field of modern archaeology. Australian archaeologist and prehistorian, Vere Gordon Childe was a pioneer in prehistoric classification schemes, opening the way for the integration of field work findings into the temporal and cultural frameworks of world history. Play the Past guest author Owen Vince noted that Childe’s legacy may have also impacted the world of computer games, for example, in the modeling of core concepts and mechanics of the Age of Empire franchise. By taking Childe’s concept of “technological thresholds” as its core micro- and macro-gameplay loop with the managing and upgrading units, buildings, technologies into new “ages” of human development, Age of Empires gave Childe’s pet theory of human culture a competitive and nationalistic coloring — ironically making the game ahistorical in its overall gameplay arc and endgame outcomes.

Much of archaeological research gravitates around the discovery and evaluation of objects, everyday and exceptional, that once belonged to long-disappeared culture groups. Unsurprisingly, theoretical discussions abound on the status of found objects — and “thingness” itself — in archaeological circles. Which begs the (archaeogaming) question: how can the relation between the player and objects shed light on the ontology of objects, as posited by archaeology? In Is The Secret of Monkey Island … Thinginess?, Namir Ahmed coordinator of Ryerson University’s Digital Media Experience Lab, investigated this issue, as a philosopher-player of The Secret of Monkey Island, a classic point-and-click 2D adventure title from Lucasfilm Games. The reuse of found objects, or quest objects, in different (and sometimes unusual) contexts is key to solving puzzles in Monkey Island, allowing players to unlock the narrative forward. The gameplay focus on objects with regards to their recombinant utility, argued Ahmed, could help bridge a gap in the archaeological study of objects between the study of culture (context) and the classification of object morphologies (form).

To compensate for the reductionist habit of academic video game criticism, Play the Past has set an activity universal to all human (and animal) culture – play – as its philosophical rallying cry. Many of our core contributors have written innovative essays to assay this notion, and impulse — witness, Toy Stories and What do Action Figures have to Teach Us by RobMacDougall, The Unexamined Game is Not Worth Playing by Jeremiah McCall, or Play the ancient game by Roger Travis.

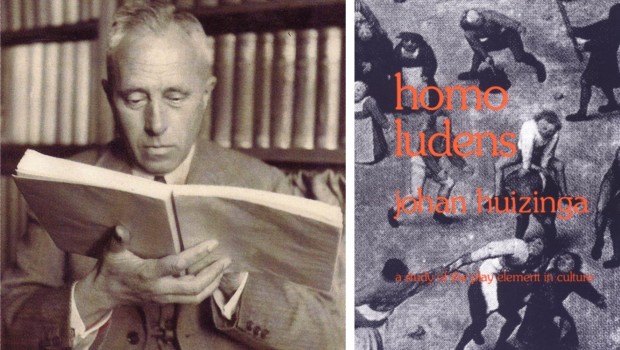

Perhaps one of the most insightful unpackings of the “play” impulse ever to be published on our blog has come from guest author Andrew Salvati, today an adjunct professor of Media Studies at the College of Liberal Arts at Drew University. In his post, Salvati proposed “to take a broad perspective on meaningful play by exploring the ways in which the writing of historical narrative might itself be conceptualized as a playful endeavor.” Summoning the spirit of a foundational thinker of play, Johan Huizinga, and the lessons gleaned from the post-modern linguistic turn, Salvati examined the play functions embedded in the rules of empirical historiography favored by academic historians. The perceived gap that separates “serious” historiography from popular history forms such as games, literature, mashups and satire, Salvati suggested, could be bridged by shining the light on the nature “serious play” — as can be seen at work, for example, in empirical peer-reviewed historical literature.

Anybody who has taken the deep dive into the table-top RPG hobby or is a member of an historical reenactment group knows how transformative such “mere hobbies” can be. What is it about role-play that compels us to give all of our spare time and the best of ourselves over to acting the part of somebody else, either a fictional character or a historical ancestor? Can historical reenactment, taken to an extreme, be construed by its participants as a form of “time-travel”? Reviewing Anja Dreschke’s 2011 documentary Die Stämme von Köln (The Tribes of Cologne) for Play the Past, Professor of Archaeology at Linnaeus University Cornelius Holtorf probed the driving passions and theoretical implications behind historically-informed group cosplay in small community groups given over to transgenerational practices of historical reenactment. Following Dreschke’s instinct for close observation of reenactment tribes “in their habitat”, Holtorf linked the local cultural traditions of carnival in Cologne (Germany) to the life-long pursuit of historical truth by reenactors who mix academic research with artisanal creativity in their play of persona. The reputation of reenactors as nostalgia-obsessed hobbyists is given the lie, as Dreschke’s compassionate camera uncovered complex motives for reenactment, most notably the need to creatively envision the future by immersing oneself into past modes of being.

Eurocentrism and the Post-colonial Gamer

Put simply: can one produce an effective critique of colonialism by playing computer games ?

In The Joys of Imperialism, The Political Economy of Strategy Games guest author Luke Pullen probed his own enjoyment of Frog City Software’s obscure strategy title, Imperialism, to suss out the banality of evil of colonial conquest through the lens of a management sim. Frog City’s Imperialism differs from its more famous cousin, Sid Meier’s Colonization (also famously critiqued on Play the Past) with its simulation of post-mercantilist economic policy and its simplified model of 19th-century world markets. In Imperialism, the endless hunger for new territories to conquer is tied to economic conditions at home, with the need for imperialist powers to ever look outward to resolve domestic growth dynamics. Thus, in contrast to Civ-like sims that separate concerns of war and expansion from banal economic activity, Imperialism uncannily mimics the joint effort of war cabinet and trade board, as they have historically proved to be codependent with colonial powers such as Spain, France and Britain.

“Regardless of the strategy you adopt, Imperialism is a game about subjugating other peoples. In fact, it doesn’t even represent other populations: as an imperialist, the only human beings you see are soldiers, industrial specialists and the workers who reside in your capital. In a deeply appropriate metaphor, the imperial capital, the spider at the centre of the web, is the only location where Imperialism depicts ordinary human beings. Other people exist only implicitly, in various towns and cities dotting the map. Once absorbed, the natives are never restless, and do not speak. The empire’s serfs, slaves, colonists and coolies are implied by the extraction of resources, but never shown. To the player, the world of Imperialism is only land to be exploited and markets to be controlled.

In one sense, then, Imperialism is an especially cynical example of the genre’s problematic moral outlook. The thing is, I find that Imperialism’s brand of disarming sociopathy has a critical purpose: the extent of the game’s ruthlessness, and its fixation on economic minutiae, provide an unflattering lens (monocle?) through which to view other strategy games and the political and economic discourses they inhabit.”

Being tied at the umbilical cord to a technology of control — information technology — video games are famously biased toward narratives of imperial war and conquest. With articles such as Seeing Like SimCity by Rob MacDougall, or if (!isNative()){return false;}: De-People-ing Native Peoples in Sid Meier’s Colonization by Rebecca Mir and Trevor Owens, Play the Past has hosted some important discussion on the reification (i.e. the making into knowledge objects) of culture and people, for example in management sims and strategy games. In her earnest plea to move the conversation beyond critique, archaeological consultant Franki Webb looked at how game developers have traditionally represented indigenous cultures in stereotypical ways. If game developers today show more sensitivity and respect toward indigenous cultures than in previous decades, as Webb argued, decolonization of game narratives can only come with integral indigenous participation in the game development process.

“Teacher Design Notes”

Aside from hosting critical discussion of history and games, Play the Past has also provided an online venue for educators to share their experiences with the new modes of teaching and learning offered up by games — “game-based learning”. From the uses of Minecraft and other commercial games, to the design of interactive stories, ARGs and role-plays, guest authors have been especially fruitful and forthcoming with their contributions to the conversation.

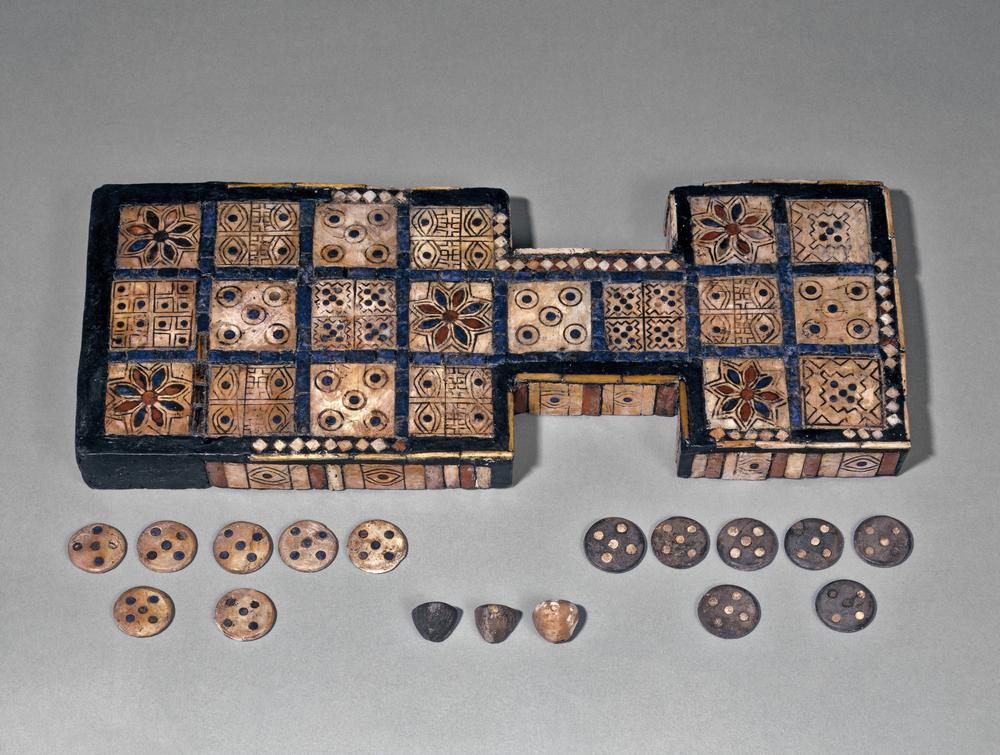

Reviewing the oldest board game of the world for Play the Past, Namir Ahmed accidentally stumbled on fundamental design concepts of strategy games while playing a late night session of the Royal Game of Ur. Thanks to British Museum curator Irving Finkel’s reconstruction of the ancient rules, modern players can experience this competitive race board game, which combines dice rolls and capture moves. Cognizant of the risk/reward ratios programmed into the Royal Game of Ur’s simple rules, Ahmed derived a few unsettling lessons for designing educational games: educators, remove competitive elements at your own risk!

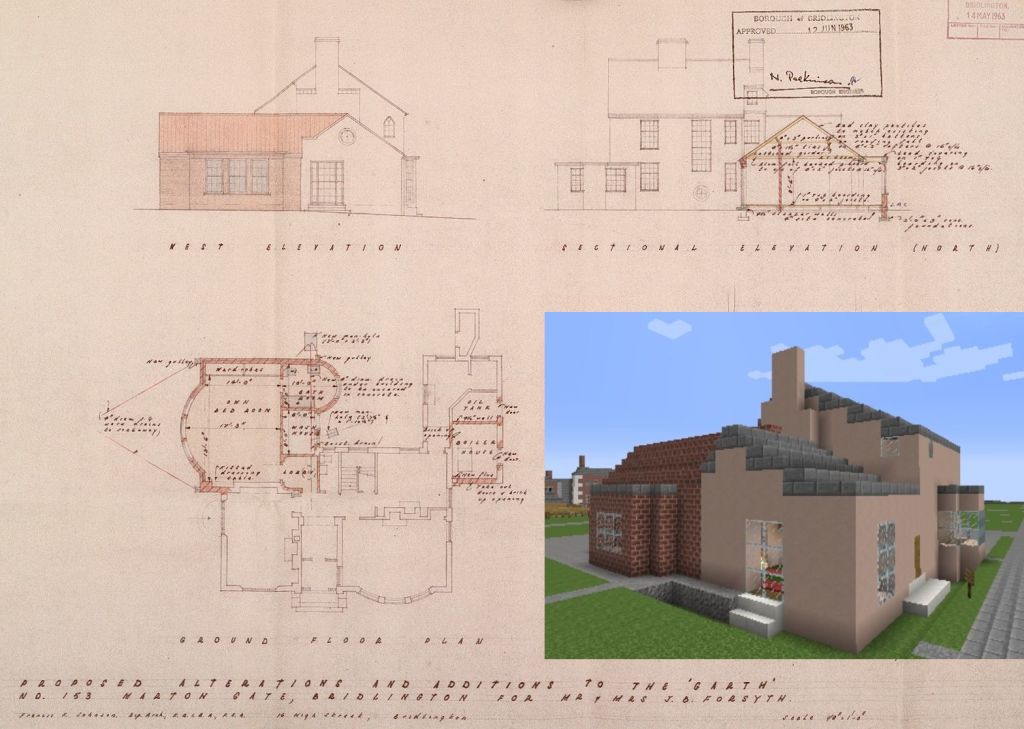

Yes, but what about Minecraft? In its declawed (i.e. violence-free) edition, Minecraft reigns triumphant in the pantheon of educational video games, particularly in the United States. In Minecraft as a 3D Cultural Heritage Modeling Tool in the Classroom, Latin and ancient history teacher at Winston-Salem Forsyth County Schools, Jessie Craft gave context to the legitimization of Minecraft (Education Edition) in educational circles. Craft also shared notes on the preparation of a Minecraft Edu class project in which students were tasked with reconstructing buildings of ancient Rome from architectural plans using primary and secondary sources. In her account of a history class teaching experiment on Play the Past, guest writer Hannah Rice also sought to identify the learning drivers that Minecraft offers for teachers who want to introduce their students to the world of archives. Designed as an outreach program for the Hull History Centre, the HullCraft project made digitized architectural plans of local historical buildings available to youth groups for educational activities involving “digital restoration” of architectural scale models in Minecraft. The virtual architectural experiments also enhanced students’ sense of place, by referencing existing buildings known to or visited by participants.

Can games help teach difficult topics that arouse historical controversy? For example, can one tell the story of the American Civil War (1861-1865) by letting students take on the role of one of its “bad guys”, confederate general John Hunt Morgan? Human-computer interaction expert Paul Gestwicki of Ball University recounted the game development effort he undertook with some of his undergraduate students of Morgan’s Raid, a game about the Civil War in Indiana. Over three 15-week semesters Gestwicki and his student crew embarked on an iterative design process of their educational game, complete with prototype testing and software implementation. Gestwicki’s account of the design process on Play the Past placed emphasis on the narrative conundrums of teaching history through role-play of period actors who today are cast in a cut and dry moral framework. Student perceptions of the Confederate Army protagonist were fed back into the narrative design of the game, so as to maximize productive discussion of the historical event, through the game’s interactive exposition of historical facts.

In The Future of the Civil War through Gaming: Morgan’s Raid Video Game, Gestwicki’s Ball University collaborator, history professor Ron Morris, broke down for Play the Past readers the role of the historian in the development process and teaching implementation of educational games with historical themes. Morris summarized the role of the historian under three rubrics: “fact checking, process identification, and curriculum collaboration”. Fact checking involves ascertaining names, places and dates and connecting the game narrative to empirical historical sources. What Morris called “process identification”, relates to the core set of interpretive questions the player will be taking on when playing on a historical role, and how the narrative focalizes a given aspect of the history at play. Finally, historians can also help game developers design historical play spaces that connect to curriculum goals and outcomes. Morris then completed his “historical game design tour” by examining the place of interactive media in a learning ecosystem of research, curricula, and cultural institutions.

“How often can you say the government paid you to go down the rabbit hole?”

Thus begins, provocatively, one of Play the Past’s most comprehensive explorations of Augmented Reality Games (ARGs) in the classroom, by digital humanities expert Amanda Visconti. Visconti and her University of Maryland College of Information Studies colleagues were recipients of an National Science Foundation EAGER grant in 2010; that funding went toward the development of a prototype ARG that went under the name of Arcane Gallery of Gadgetry (AGOG), for teaching middle school students skills critical to STEM, information literacy, and historical thinking. Visconti and her core collaborators went on to assemble together a crack team of researchers and game and UX developers who set their sights about designing a scalable set of gamified teaching modules around a single narrative premise: a counterfactual exploration of “secret inventors” whose inventions surface throughout US history and reside in “an imaginary collection of retro-futuristic objects that at one time allegedly resided in the US Patent Office”.

The Augmented Reality Game (ARG) format and AGOG’s core mythology deliberately blurred fact and fiction in order to stir the investigative juices of students and aid the acquisition of information literacy and historical thinking skills. In a follow-up post, Visconti assessed the ethical implications of placing counterfactuality (or hypothetical historical outcomes) at the center of AGOG’s teaching methodology. As AGOG pushed the envelope of historicity, some students were destabilized by the activity of turning historical fact and reality into an open question. ARGs that employ counterfactuals therefore require teacher-facilitators who are attentive to the emotional impact of students’ questioning of historical materials, and who can ground the ambiguity of self-reflexive play into positive outcomes. At bottom, these investigative play experiments require both elements of risk and trust to succeed in their goals, and Visconti explained how savvy instructional design could help students distinguish between fact and fiction.

Frustrated with traditional rote learning methods in Malaysian high school history curricula, educator Michelle Low set about creating a set of “live” history role-plays for her students to explore world-historical events from a historical participant perspective. For Play the Past Low delivered an account of her design and attempts at deploying these role-plays for targeted student groups, complete with screen captures of class activities and collaboration documents. In Playing with Power: An Alternative World War 2 Role Play, Low gave her students a World War 2 counterfactual scenario, and encouraged them to exercise their narrative creativity and build historical literacy skills in a collaborative context. Split into teams, students played some of the major “factions” (nations) involved in the war, throwing in the fictional nation of Wakanda (from the Marvel comic series and the movie Black Panther) to force counterfactual reasoning into the conflict. Though the relation to historical fact remained somewhat elastic with students, historical thinking habits made a perceptible appearance with the students most engaged with the simulation.

In a follow-up article, Low recounted a second role-play experiment, this time with the French Revolution as narrative backdrop. Low’s design for her second role-play differed from her WW2 role-play, with better focus on factual historicity and participant interplay. For this role-play, factions were not competing nations, but competing social groups roughly modeled on the classic “three estates” of Ancient Régime French society: the nobility, the clergy and… the Jacobins, portraying the radical wing of the third estate. Low provided details on the overall structure of the role-play (over sessions), how roles were divided among students, which collaboration tools students used in teams, and how students were to be assessed for this “assignment”. Low also recounted her role as facilitator, and how she adjusted rules as the counterfactual historical plot enfolded. Exhausted and relieved to return to standard curricular fare at the end of the role-play, some of Low’s students also remarked how they had, for the first time in their lives, “really thought about the French Revolution”.

Conclusion

Though it is too early to tell what the future looks like, the Play the Past community continues to connect through informal discussion, and the blog remains open to new-comers interested in contributing insightful writing about the intersection of games / play and history, “broadly defined”. With many struggles still to surmount, the “alive and well” status of the community reaching the 10th anniversary mark bodes well for the future.

Above and beyond what has been said above, we owe a debt of gratitude to you, Play the Past readers, who continue to visit our blog and engage with the writers who have seeded the many insightful discussions to be found. A Big Thank You to all who have made this project happen, and whose contributions and participation to this project have made Play the Past the premier blog for Historical Game Studies on the web.